Last updated on July 29th, 2022 at 07:50 pm

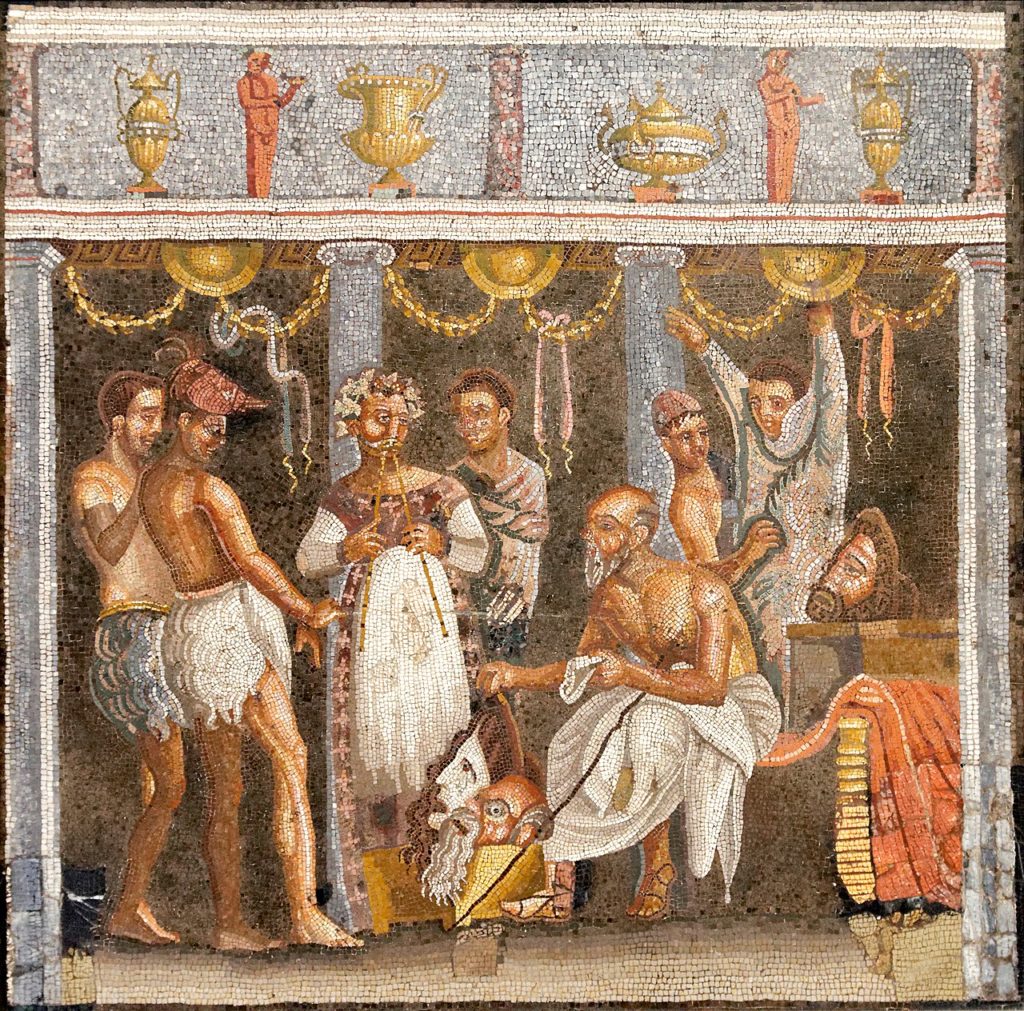

A visitor today to the ruins of the town of Pompeii, which was buried under volcanic ash and rock following the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, will be confronted by many frescoes, mosaics, and wall paintings showing people and mythological figures playing musical instruments.

These scenes in places such as the Villa of the Mysteries highlight how central music and the instruments were to Roman life.

But unlike Roman history, philosophy, architecture, or literature, the remains preserved in writing or stone today, we cannot obtain a recording of a Roman song.

We are left to try to piece together what Roman music sounded like from disparate sources.

What instruments were there in Ancient Rome?

The Romans used many musical instruments, several of which are either known or used in the modern world. Many were forerunners of instruments that we use today.

For instance, they used the pandura, a lute-like instrument. It was effectively a small guitar with four strings instead of the more usual six on a modern guitar.

There were many different types of percussion instruments. For instance, tambourines and drums were used, as well as a device known as the scabellum, a kind of clapper played with one’s foot.

This latter one had the advantage of being something somebody could use while playing the main instrument with their hands.

The cymbala were little metal disks tapped together to make a rattling sound.

Romans played various types of pipe organs as well. A particularly notable one was the hydraulis, a large kind of organ that used water pressure to create a loud noise.

However, none of the Roman instruments used were as crucial as the lyre. This instrument was somewhat similar to a harp but was considerably smaller.

One cradled it in their arms with one hand and played it with the other by plucking the strings of the device. This instrument had become esteemed as the height of musical culture in the Eastern Mediterranean from the sixth century BC, and Roman culture absorbed it as a result.

However, eventually, the Romans innovated in its use, developing the cithara or kithara. This was larger and heavier than the more traditional lyre and emitted a louder noise when played.

It lies somewhere between a harp and a guitar in modern instrumentation. The name itself is that from which the word guitar has evolved.

Who Influenced Roman Music?

It should be noted when examining these instruments that the Romans were not exactly innovators in this field.

For instance, lute-like instruments had been used by the ancient Egyptians and in Mesopotamia, the region approximating Iraq today, for thousands of years.

Flutes had been used by the Etruscans, a people who ruled an advanced civilization in Tuscany during the seventh and sixth centuries BC when Rome was still little more than a collection of villages on the banks of the River Tiber.

However, as with so much of their culture, the Romans were primarily indebted to the Greeks. It was from them that they acquired a whole array of different instruments, most notably the lyre and various types of pipe instruments.

What Was Roman Music Like?

As with their instruments, the Romans were profoundly influenced in their music by the cultures of the Mediterranean which preceded their own, notably those of the Greeks and the Etruscans.

This was heavily instrument centred, rather than being based on lyrics being sung. Nevertheless, there were often lyrics involved too.

One famous example which has come down to us is the ‘Secular Hymn’ or ‘Song of the Ages’ which the poet Horace was commissioned to write by the Emperor Augustus in 17 BC for the celebration of the Secular Games. This began as follows:

“O Phoebus, Diana queen of the woodlands,

Bright heavenly glories, both worshipped forever

And cherished forever, now grant what we pray for

At this sacred time,”

It is clear that lyrics where they existed tended to overlap with the rhyming structure of Roman poetry and epic literature and Roman music, such as it was, was an extension of Roman literature set to music.

It would have all been heavily instrument-based, with pipes, organs, flutes, lyres, and guitars forming the major basis of it.

While percussion instruments did exist, as we have seen, they would not have been central in the ubiquitous use of drums in modern popular music.

Many instruments would have been played to musical notation, which Romans had also acquired from the Greeks.

Music and Roman Society

Our inability to listen to Roman music today is frustrating when we know how central it was to their society.

The regularity with which we see musical instruments depicted on the walls of villas and houses at Pompeii attests to this.

Much of this would have been as background music for social events. It is not difficult to imagine Roman patricians visiting each other’s homes on social occasions to hear a kithara or lyre being played in the background.

However, much of it would have been at more formal occasions, notably religious festivities.

Music and religion were inseparable in the ancient world. Apollo was one of the foremost gods and the patron of music and dance. His supposed son Orpheus was closely associated with the lyre.

Minerva, the Roman equivalent of Athena, was said to have conveyed the use of the aulos, a type of flute, to humanity. Faunus, the horned god of the forest and the equivalent of the Greek deity Pan, was typically depicted playing the flute or the pan-pipes.

Unsurprisingly, these associations between the gods and music meant that religious festivals would have featured music heavily.

Indeed, Horace’s ‘Song of the Ages’ was dedicated to Apollo and Diana.

Finally, the Romans, no doubt like most other nations throughout history, made war to the sound of drums. Various other instruments and organs and percussions would have been used in the immense ‘triumphs’ which were held in Rome to celebrate the deeds of a victorious, conquering general throughout the Roman Republic.