In truth, the Vegas of today resembles little the Vegas of yesteryear, on the surface, anyway. But one needs only stroll through the Mob Museum in downtown Las Vegas to remind them of “Sin City’s” not-too-distant past.

There the names Meyer Lansky, “Bugsy” Siegel, Gus Greenbaum, and Moe Sedway aren’t torn from newspaper headlines or the pages of True Crime magazine, they represent the long list of criminals legitimized to accommodate the building of a city in the middle of the Mojave Desert to systematically fleece railroad workers and dam builders of their hard-earned pay by supplying what they’d be most willing to pay for: sex, gambling, and drugs.

For the best part of a century, Vegas functioned as a largely autonomous, mob-owned business venture where crime ran rampant, and criminals acted with impunity. Not until the 1980s did Organized crime finally loosen its hold.

Rising From the Desert

The settlement of Las Vegas, Nevada, was founded in 1905 following the opening of a railroad that linked Los Angeles, CA, and Salt Lake City, UT.

At first little more than a rest stop, Las Vegas began attracting farmers (primarily from Utah) once fresh water was piped in. Water availability in the middle of the desert allowed Las Vegas to become a water stop: first for wagon trains, then railroads connecting Los Angeles and points east.

In 1911 the tiny town was incorporated into newly-founded Clark County.

For a while, two towns were named “Las Vegas.” The east side of Las Vegas, which encompassed modern Main Street and Las Vegas Boulevard, was owned by US Senator William Andrews Clark (the majority investor of the railroad), while the west side of Las Vegas, which encompassed the area north of modern-day Bonanza Road, was owned by surveyor J.T. McWilliams, who purchased a section of land after being paid to survey it. It was the latter Las Vegas that we know today.

Ironically, for a city always known for its vices, on October 1, 1910, the State of Nevada outlawed gambling (the last western state to do so), and ten years later, a nationwide constitutional law prohibiting the production, importation, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages went into effect in the US.

If either law had remained in place, it’s unlikely that either Las Vegas would have survived.

“Sin City”

By 1906, and the opening of the railroad that linked Nevada to California, an area known as Block 16 (and nearby Block 17), located on First Street between Ogden and Stewart Avenues, had already become known as an oasis for alcohol and prostitution, known as “Sin City.”

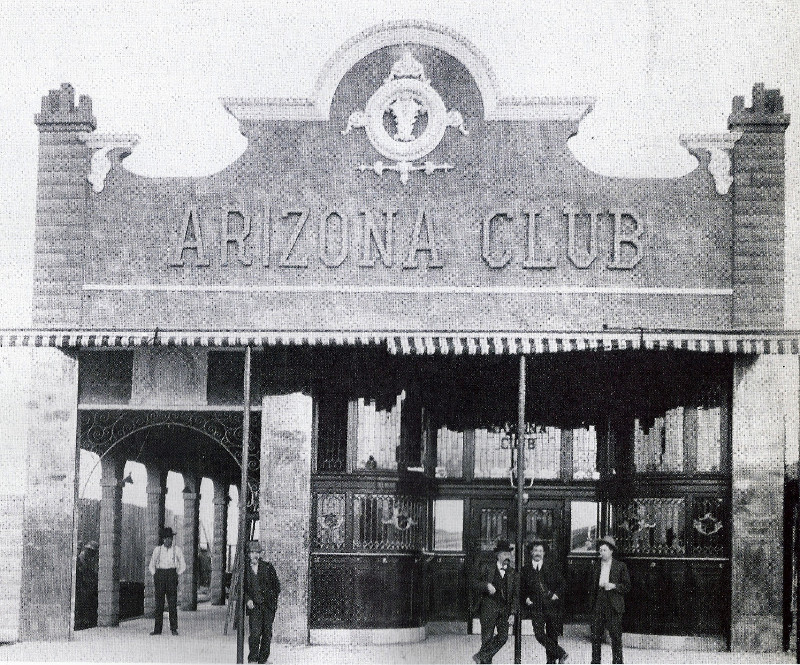

The first of the Las Vegas establishments granted a license to legally sell liquor, saloons like the Arizona Club sold drinks to railroad workers and rented out backrooms to prostitutes where customers could be serviced 24/7 for a percentage of their earnings.

By 1912, despite the state-wide outlawing of gambling, the Arizona Club became a gaming hall boasting “all vices are fully available.” Thus, the Arizona Club (and several other less conspicuous Las Vegas establishments) was invested in gambling nearly two decades before it was legal in the state of Nevada, and so-called “Organized Crime” cut themselves in.

The Hoover Dam and the First Legal Casinos

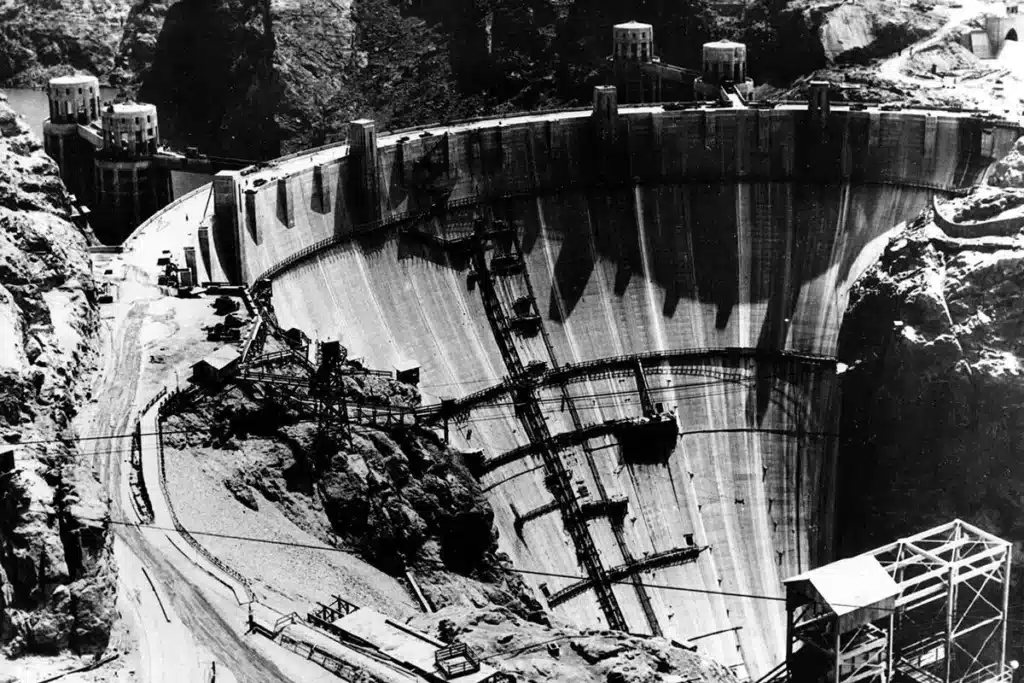

On July 3, 1930, US President Herbert Hoover signed into effect the bill to construct the Boulder Dam (later renamed Hoover Dam). Once construction began in 1931, the population of Las Vegas grew from about 5,000 to 25,000 almost overnight—most flocking there to get construction jobs.

In that, the majority of dam workers were men, a market for large-scale entertainment likewise grew—almost overnight. Recognizing the potential for huge profits, many Organized Crime bosses from the east approached Las Vegas business owners with a joint-venture proposal: constructing multiple casinos with showgirl theaters to provide “entertainment.”

Realizing that gambling was good for local growth, in 1931, 20 years after banning it, the Nevada Legislature legalized casino gambling, effectively encouraging the thousands of dam workers to spend their hard-earned cash at their establishments.

These workers were soon joined by hundreds of thousands of tourists who came to witness the dam’s construction—but also took advantage of the gambling establishments and “easy” women.

In that Las Vegas already had a small-but-well-established illegal gambling industry before legalization, the city was poised to begin its rise as the world’s gaming capital.

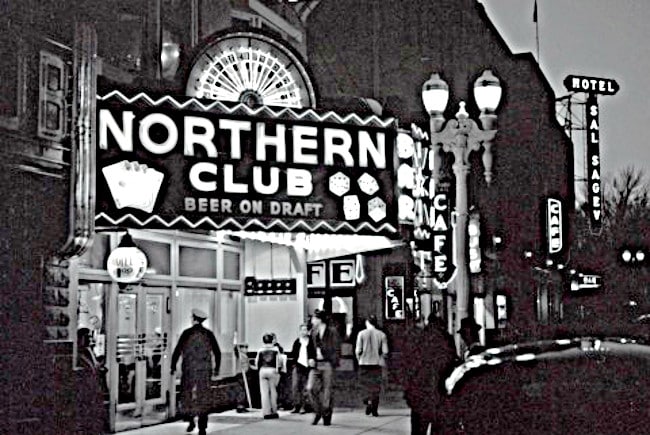

The first gambling license was issued to the Northern Club, and soon after, other casinos on Fremont Street, including the Las Vegas Club and Hotel Apache. Then to accommodate the new influx of residents and visitors, Fremont became the first street to be paved and first to have a traffic light installed.

Organized Crime: Expansion

Quickly becoming known as a city where all manner of vice was available for a price, the Las Vegas tourist industry grew—effectively encouraging the spread of Organized Crime for which the city became famous.

In the early 1940s, a slow shift began to occur in new casino construction locations. With the downtown market (centered around Fremont Street) becoming congested and burdened by rising taxes, alternate locations were considered.

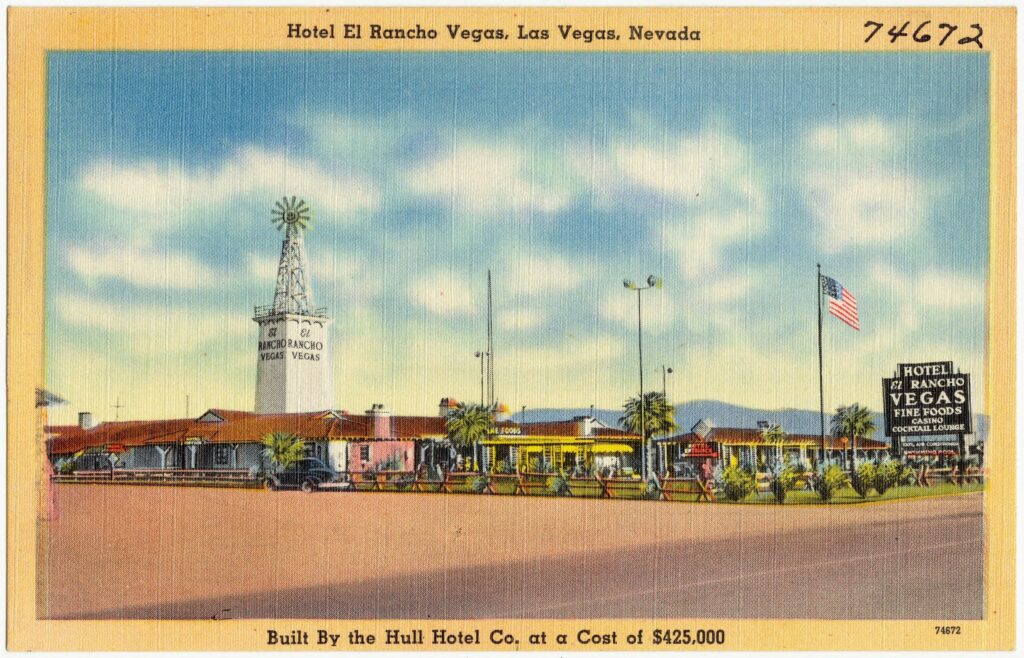

In 1940, El Rancho Vegas, one of the city’s first resort-style hotels, opened south of the city on a stretch of the LA Highway that would become known as the “Strip.” The Last Frontier quickly followed that in 1942, a sprawling development with a Western motif reflected it its slogan, “The Old West in Modern Splendor.”

In 1945, Billy Wilkerson, a wealthy entrepreneur who owned newspapers, restaurants, nightclubs, and hotels, purchased land south of the Last Frontier with plans to build a luxury resort and casino, a resort he planned to call the Flamingo. But Wilkerson soon ran into financial difficulties, forcing development to cease.

A short time later, New York crime boss Meyer Lansky approached Wilkerson, offering to help with the finances—which Wilkerson accepted. Lansky had been operating successful gambling establishments in Florida, New Orleans, and Cuba since 1936 and knew the industry well.

Lansky enlisted the equally-notorious mobster Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel to oversee his Las Vegas investment. Though relatively new to the gaming industry, Siegel quickly learned the ins and outs.

Who was Meyer Lansky?

Commonly referred to as the “Mob’s Accountant,” Meyer Lansky was a member of the Jewish syndicate and the first heavy-hitter of Organized Crime to invest heavily in the Vegas gaming and hotel industry.

Over a span of forty years, Lansky developed a gambling empire that reached around the world, owning pieces of casinos in several counties.

Along with his associate Charles “Lucky” Luciano, Lansky was instrumental in developing the National Crime Syndicate in the US and became a powerful influence on the Italian-American Mafia.

Lansky came to play a major role in consolidating the entire criminal underworld and was instrumental in directing mob money to money-making ventures such as those in Vegas.

By the time Lansky died in 1983, he’d achieved the distinction of being one of the wealthiest gangsters in American history; his success was due in no small part to knowing how to delegate responsibility and associating with men he could trust.

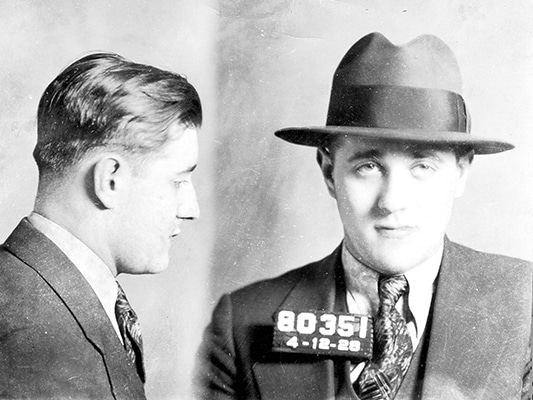

Who Was Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel

A childhood friend of Jewish mobster Meyer Lansky, Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel founded the infamous Murder Inc. hit-man organization, the enforcement arm of the Italian-American Mafia and National Crime Syndicate. d

One of the first mobsters to be referred to as a “celebrity gangster” (because of his reputed charm and handsome looks), Siegel was noted for his prowess with guns and ease of committing violence.

Initially a major bootlegger during the US Prohibition (1920 to 1933), Siegel switched to gambling when Prohibition was repealed and moved his operation to California, where he dabbled in gambling but functioned primarily as a hit-man for his Organized Crime bosses.

In the early 1940s, Siegel moved to Las Vegas, where he established himself in the burgeoning gaming industry by purchasing a few of the first casinos. This put him in a prime position to accept Meyer Lansky’s offer to oversee his (and other Organized Crime) Las Vegas hotel and gaming interests in 1945.

No Honor Among Thieves

By 1946, Meyer Lansky had squeezed Wilkerson completely out of the Flamingo deal and put “Bugsy” Siegel in charge of operations. This established the business model for all future Las Vegas casinos: they would be funded by Organized Crime syndicates back east via laundering millions of dollars through local businesses.

That same year, Lansky convinced his New York and Chicago associates to put Siegel in charge of all their Las Vegas holdings. But then Siegel decided to put his life-long friendship with Lansky to the test.

“Bugsy” began skimming deeper and deeper into casino profits, claiming the Flamingo was losing money, thinking he was bullet-proof under Lansky’s protection. And whether it was for skimming, proving himself an incompetent manager, or because of his blatant arrogance, when the order came down, Lansky did nothing to intervene. Siegel was shot dead in Beverly Hills, California, on June 20, 1947.

According to Mob lore, twenty minutes after the Siegel hit, two of Lansky’s gangland associates, Gus Greenbaum (who ran El Cortez casino) and Moe Sedway (who helped finance the Flamingo Hotel) walked into the Flamingo and assumed control—as if nothing had happened.

Enter Howard Hughes

To expand Las Vegas’ gambling and prostitution operations, bigger and more elaborate casinos and hotels were built by Organized Crime bosses during the 1950s.

But by the early 1960s, Vegas had expanded as far as it could without major financial investment. However, Organized Crime syndicates in New York and Chicago decided that further investment would open them up to IRS scrutiny. The Fed’s taking down Al Capone in ’31 for tax evasion had taught them a valuable lesson.

In an unrelated situation, in 1966, American business magnate Howard Hughes sold his controlling interest in Trans World Airlines for $547 million dollars, and to avoid paying the exorbitant taxes levied by his home state, California, sold his properties there and moved to Las Vegas, renting the top two floors of the opulent Desert Inn.

In 1967, Hughes decided to purchase Desert Inn—then proceeded to buy several other hotels and casinos quickly from Organized Crime bosses (now eager to take their profits and move on, just ahead of rumors that the FBI was planning a crackdown on their operations).

Legitimacy and the End of Mafia Control

In buying Desert Inn, Sands, Frontier, and then Castaways, Hughes had effectively gutted mob-controlled Vegas in quick order (whether that was his intention or not).

At the peak of his buying spree, Hughes controlled almost one-third of the gaming revenue on the “Strip” and became one of the most powerful figures in the entire state of Nevada.

One result of Hughes’ dominance of Vegas gaming was providing the legitimacy lacking under Organized Crime control, which had prevented the passage of the Nevada Corporate Gaming Act.

The Gaming Act would negate the long-standing requirement that every shareholder of a company owning a casino be licensed (undergo a criminal background check).

Now for the first time in Vegas history, large, publicly-traded companies could invest massive sums of money in the gaming and entertainment industry, turning what had been a series of small (but lucrative) independent hotels into luxurious resorts the likes of which the world had never envisioned for the middle of the desert.

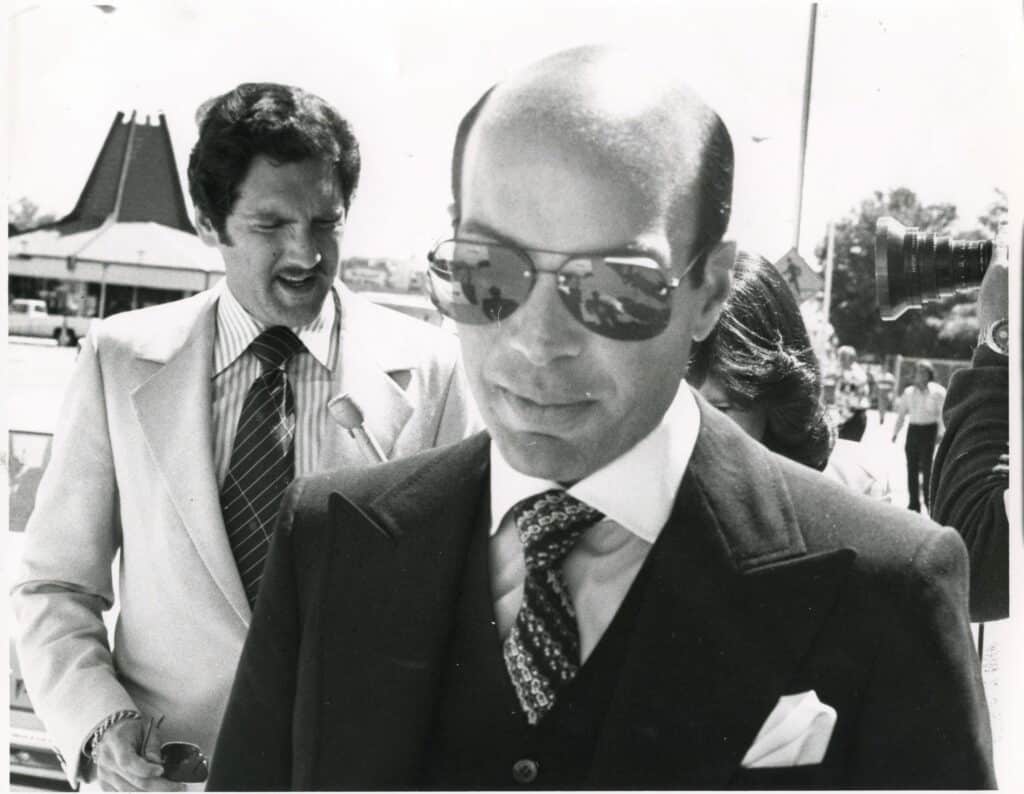

Allen Glick and the Final Chapter in the Vegas Organized Crime Saga

In 1970, Congress passed the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) as part of the government’s war on organized crime.

It allowed prosecutors to pursue crime families and their sources of revenue–both illegal and legal. But even with this tool in place, it wouldn’t be until the late 1980s that organized crime would no longer be a controlling factor in Vegas gaming.

In the early 1980s, the Nevada Gaming Control Board began an investigation into Allen Glick of the Argent Corp., who they suspected of having ties to organized crime. (Glick owned the Stardust, Fremont, Hacienda, and Marina—a number of hotels second only to Howard Hughes).

Dramatized in the 1995 film Casino, the NGCB determined that employees of Glick had skimmed an estimated $7 million (between 1974 to 1976) from slot machines on behalf of Milwaukee, Chicago, Kansas City, and Cleveland Organized Crime families, who maintained hidden interests in the properties.

The Glick saga ended in 1986 with convictions and federal prison terms for more than a dozen top US mobsters, including Milwaukee boss Frank Balistrieri, Chicago Organized Crime bosses Joseph Aiuppa and Jackie Cerone, Carl DeLuna of Kansas City, and Milton Rockman of Cleveland—effectively ending all but the most underground mob involvement in Vegas.

Does Organized Crime Still Exist in Vegas?

Although Organized Crime syndicates of yesteryear are no longer the biggest investors in the Las Vegas gaming industry (most of the 136+ casinos are owned by four or five mega-conglomerates), that doesn’t mean there is no Organized Crime involvement.

In that a great number of entertainment and service industries remain under Mafia control in the US today (sports betting, narcotics, waste management, sex work, construction, high-stakes poker clubs), it would be naive to assume Organized crime hasn’t found a way to stay in the game.

Sources

History.com., “Las Vegas,” Las Vegas – History, The Mafia & Casinos – HISTORY

TripSavvy, “The Mob Museum,” The Complete Guide to the Mob Museum in Las Vegas (tripsavvy.com)

Brendan, Richard, “Las Vegas: Past, Present and Future,” https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JTF-05-2018-0027/full/html

Adams, Kathy, “Why is Las Vegas Called Sin City?” https://getaway.10best.com/12803289/why-is-las-vegas-called-sin-city

“Mayer Lansky,” https://www.britannica.com/biography/Meyer-Lansky

Biography.com., “Benjamin ‘Bugsy’ Siegel,” https://www.biography.com/crime/bugsy-siegel

The Mob Museum, “Allen Glick . . .” https://themobmuseum.org/blog/allen-glick-1970s-owner-of-las-vegas-casinos-skimmed-by-mob-has-died/

Ranker.com., “10 Things the Mafia Somehow Still Controls,” https://www.ranker.com/list/things-the-mafia-controls/philgibbons