Orichalcum is a semi-mythical metal that was most likely an early form of brass. Its name derives from the ancient Greek words for ‘mountain’ and ‘copper’.

Orichalcum was mentioned in several ancient texts, including Plato’s Critias. Plato wrote of orichalcum as being second in value only to gold, but other writers centuries later used the word to refer to a gold-colored metal of little value.

In the first century, Pliny the Elder wrote that the orichalcum mines were exhausted. One of his contemporaries wrote that the substance was “very shiny and white. Not because there is tin mixed with it, but because some earth is combined and molten with it.”

The orichalcum described by Plato was reddish-gold. Therefore, the word probably referred to different alloys at various points in time.

Cadmus and the Origins of Orichalcum

According to myth, the ancient Phoenician hero Cadmus invented orichalcum.

Cadmus was a prince descended from gods. His paternal grandparents were Poseidon and Libya, the mythical Egyptian princess. Libya was the daughter of a king and the granddaughter of Zeus. Cadmus was also descended from the River Nile on his mother’s side.

It’s an interesting origin story, because the legendary Cadmus came from a part of the world that was manufacturing bronze and brass before either became common in ancient Greece.

The Island of Atlantis

Plato’s Critias tells of how the Earth was divided up by the gods. They each ruled over their own domain. The island of Atlantis belonged to Poseidon.

Poseidon fell in love with a mortal woman named Cleito. Their firstborn son was named Atlas. He became the first ruler of Atlantis. Atlas also gave his name to the Atlantic Ocean.

Atlantis was a wealthy kingdom rich in orichalcum, which “was dug out of the earth in many parts of the island, being more precious in those days than anything except gold.”

The ancient metropolis of Atlantis was surrounded by a series of walls made of varicolored stone. The outermost was covered in bronze, the next with tin. The innermost wall or “the third, which encompassed the citadel, flashed with the red light of orichalcum.”

Within this innermost wall were palaces and a holy temple dedicated to Poseidon and Cleito. The temple was surrounded by and covered in silver and gold.

“In the interior of the temple,” continues Plato, “the roof was of ivory, curiously wrought everywhere with gold and silver and orichalcum; and all the other parts, the walls and pillars and floor, they coated with orichalcum.”

The island abided by a set of laws handed down by Poseidon, which were “inscribed by the first kings on a pillar of orichalcum”. Plato describes the early Atlantean people as having “true and in every way great spirits, uniting gentleness with wisdom”.

Later, when their blood “became diluted too often and too much with the mortal admixture, and the human nature got the upper hand” the civilization became debased and drew the attention of Zeus.

He wanted to “inflict punishment on them, that they might be chastened and improve,” but the rest of the dialogue is lost to history.

An Ancient Shipwreck

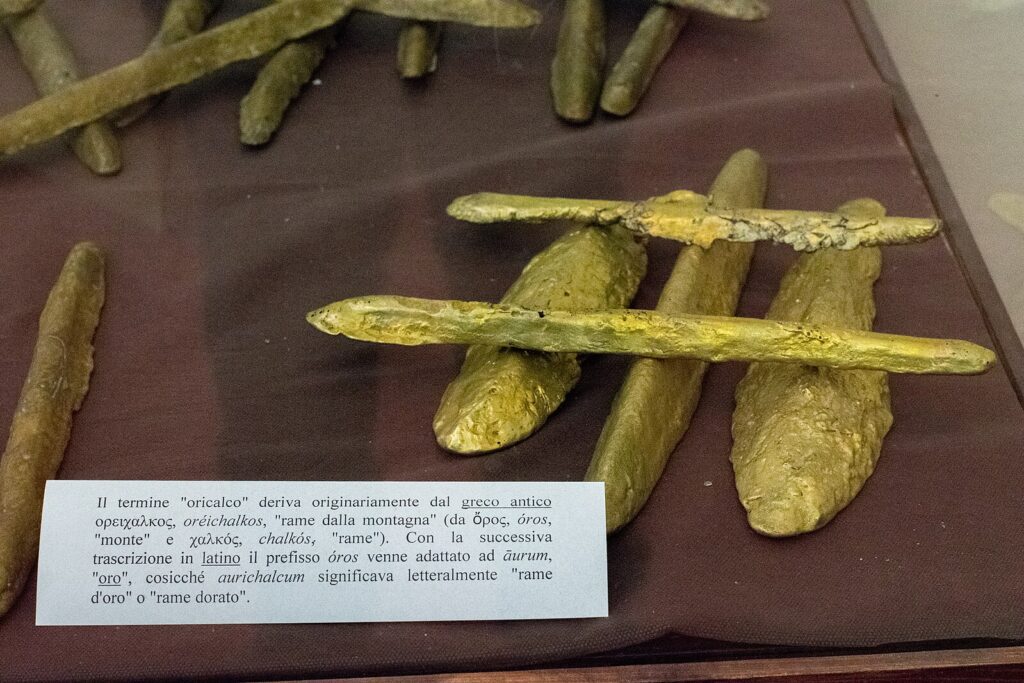

In 2015, archaeologists retrieved a unique metal from a shipwreck off the coast of Gela in Sicily.

The ship sank somewhere around 2,600 years ago. It probably departed from Cyprus, a Greek island that produced many different types of bronze. The island was so rich in copper that the word itself derives from the Greek Kyprios, which was the name of the island.

One archaeologist described the area as “a priceless mine of archaeological finds”.

Two bronze Corinthian helmets were also found in the shipwreck. Bronze is much more resistant to seawater corrosion than steel. All of the artifacts are in remarkably good shape despite having spent millennia at the bottom of the sea.

The golden ingots that they found are actually an alloy made of copper, zinc, and charcoal. Its appearance and makeup are consistent with historical references to the lost ancient metal orichalcum.

This expedition to the sunken ship in 2015 was the first time that this particular alloy had been discovered in any substantial quantities.

The metal found in this shipwreck was made through a process of cementation in which copper, zinc ore, and charcoal are melted together in a crucible. It is one of the earliest copper-zinc alloys ever found.

X-ray fluorescence shows that this particular alloy is made up of approximately 75 to 80 percent copper, 20 to 25 percent zinc, and small amounts of iron, nickel, and lead. This ratio of copper to zinc was common in early brass.

Bronze usually contains a higher percentage of copper, about 88 percent, with the rest being mostly tin. Brass, like this ancient alloy, contains a high percentage of zinc – sometimes upwards of forty percent – and small amounts of other metals.

The History of Bronze and Brass

The earliest bronze artifacts were created in the 5th millennium BC in parts of the Persian Plateau. The oldest copper-tin bronze ever found was created in Serbia around the same time. By the 4th millennium BC, bronze was being made in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and China.

The two main components of bronze – copper and tin – are rarely found in the same place. Therefore, the creation of bronze required robust trade networks.

Assyrian cuneiform tablets from the 7th and 8th century BC mention a kind of ‘mountain copper’ called oreikhalkon. It was in the 4th century that Plato wrote accounts of this substance being as rare and nearly as valuable as gold. At that time, it was still quite rare.

As time went on, the ancient Greek word oricalcum morphed into the Latin word aurichalcum, which means ‘golden copper’ and became the standard word for ‘brass’.

Brass became increasingly common and was first used for coins in the first century BC. This explains why people at this time used the word orichalcum for a metal of little worth.

It was used as coinage in isolated parts of the Roman Empire. It was also used by the government to manufacture military equipment. Roman crucibles used for the production of brass have been found in Germany, France, and Great Britain.