Last updated on July 21st, 2022 at 09:22 pm

In 1940 a new film was released by Walt Disney Productions, which sought to capitalize on the success of the studio’s first feature film a few years earlier, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

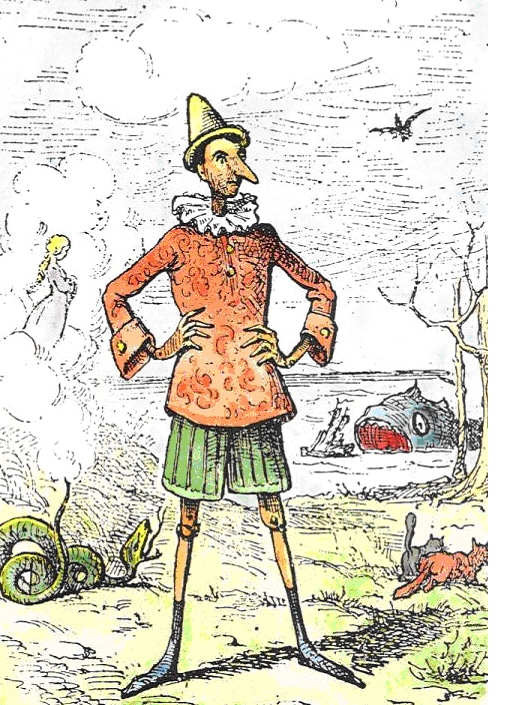

The new film, called Pinocchio, was the tale of a wooden puppet called Pinocchio carved by a woodcarver named Geppetto.

Pinocchio is soon brought to life by a blue fairy who tells him he will become a real boy if he proves himself brave, truthful, and just.

Pinocchio then sets out on a series of adventures, accompanied by the narrator of the piece, Jiminy Cricket.

In the process, he joins Stromboli’s Puppet Show and is led astray by many different characters. He becomes dishonest, a development that causes his nose to grow longer and longer every time he lies.

Later though, Pinocchio redeems himself by rescuing his creator, Geppetto, from Monstro, a vicious whale, seemingly sacrificing himself in the process.

However, the film ends on a fairy tale note when the blue fairy returns, indicating that Pinocchio is alive and did not die confronting Monstro. He is then transformed into a real boy, as the fairy had promised he would be at the beginning if he proved virtuous.

The narrator, Jiminy Cricket, is rewarded by the fairy with a gold badge that certifies him as a conscience to Pinocchio.

This ending is what one might expect from a Disney movie, a heart-warming tale about a character that goes astray and then is led back to the good path; in the end, the kind of story one tells children as an example of moral behavior.

There’s just one problem with this version of Pinocchio. It bears little resemblance to the original tale of the Italian puppet, one which was much darker than the story Disney told in 1940.

The Origins of the Pinocchio Story

It is a common misconception that Pinocchio was originally a story by the Brothers Grimm, but that’s not the case.

Disney based its film on a novel published in serial format in the early 1880s as The Adventures of Pinocchio. Italian author and journalist Carlo Lorenzini wrote this serial under the pen-name Carlo Collodi.

Born in Florence in 1826, Lorenzini became a political activist in his early adult years and fought in the Italian Wars of Independence and Unification from 1848 through to the early 1860s. These sought to remove the influence of Austria from the peninsula and unite the disparate Italian states into one nation.

Lorenzini was deeply critical of Europe’s social and political state at the time and often wrote allegorical stories to satirise Italian and European society.

In the 1870s, he began working on one such story about an amiable but rascally character who would express his views on society. He eventually wrote this as La Storia di un Burattino, or The Story of a Puppet, published in a serial format in an Italian journal in 1881 and 1882.

This work was then brought together and published in one edition as Le Avventure di Pinocchio, The Adventures of Pinocchio, in 1883. It was instantly popular and has remained so ever since as a parable about the human condition.

The Dark Side of Pinocchio

Lorenzini’s Pinocchio was much darker than the story Disney picked up and produced nearly sixty years later. In the original story, the puppet is not led astray by other figures who exploit his naivety, as in Disney’s film. But instead, he is a natural scoundrel from the beginning.

As soon as he can walk, his first action is to kick Geppetto and run away into town. There he is found by an Italian policeman who assumes that Geppetto has mistreated Pinocchio.

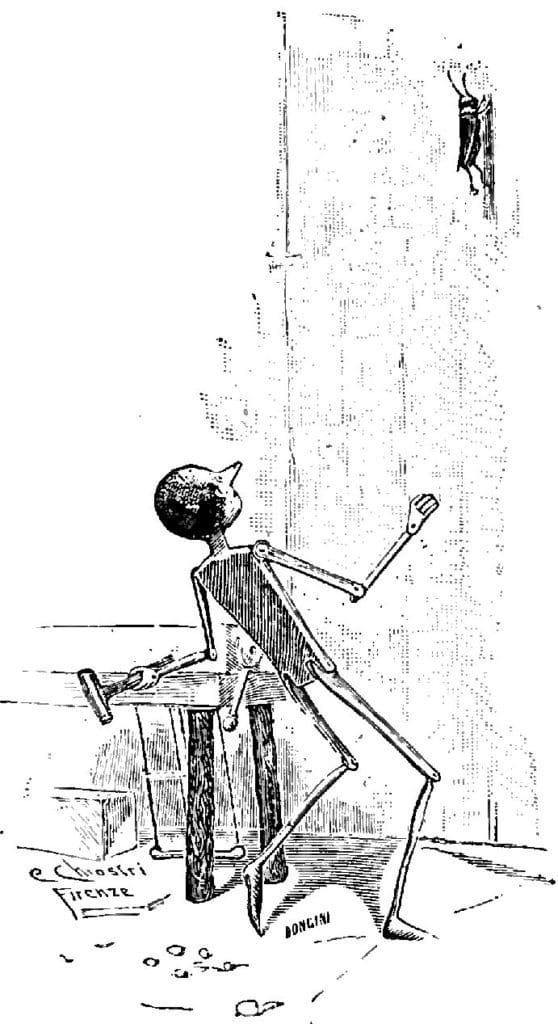

As a result, the poor puppeteer is arrested and sent to prison. Jiminy Cricket then shows up and warns Pinocchio about being hedonistic and untruthful.

Pinocchio’s reaction to such warnings is pretty different from the film. In the original, he throws a hammer at Jiminy and takes his life.

At this stage, Geppetto is released from prison and returns home, where he convinces Pinocchio to attend school and even sells his only coat to buy the puppet his schoolbooks.

The following day Pinocchio sets off but never makes it to school. So instead, he sells his books to buy tickets to the Great Marionette Theatre. And so it goes on, with Pinocchio being led astray in some instances but engaging in selfish, idiotic behavior in others.

We see a blue fairy and a promise to turn Pinocchio into a real boy if he acts virtuously, but you don’t see Jiminy Cricket again after Pinocchio takes him out him early in the novel. Lorenzini’s original version was much darker than what appeared in American cinemas over fifty-five years later.

Sanitizing the Story of Pinocchio

Disney studios made a deliberate effort to sanitize the story of Pinocchio when making the film in the late 1930s. The original is a parable about how individuals are deceitful and duplicitous but can better themselves if they attempt to do so.

Lorenzini was also trying to comment on the impact of industrialization and how those unprepared for the new world they lived in could become harmful actors within it, just like Pinocchio.

More broadly, Lorenzini was trying to say that children who, like Pinocchio, don’t attend school will become morally compromised.

We see this towards the end when, like in the film, a whale swallows Geppetto, but when Pinocchio sets out to find him, the fairy appears and tells him he needs to go back to school and stop being so lazy.

Ultimately the original was a parable about education and industrialization. However, Disney toned down these story features and, in effect, sought to portray Pinocchio as being led astray by others.

Disney essentially removed the social commentary. The most glaring aspect of this was in the story arc of Jiminy Cricket. He is Pinocchio’s friend and ally in the film. However, in the original, Pinocchio kills him early on. Thus, while the movie of 1940 and the original novel of 1883 share many similar details, Disney considerably changed the story to make it more of a fairy tale rather than a dark social satire.

You are right, it is exact