In the deep, shadowy depths of American history, few organizations have captured the public imagination, stirring up fear and apprehension, quite like the Pinkerton Detective Agency.

Whether its agents were tracking down notorious outlaws in the Wild West, infiltrating unions, backroom negotiations, or working to protect the life of the President, the Pinkertons were a force to be reckoned with.

As the agency’s influence and power grew, so did the storm of public discontent around it. Accused of far more than just violence and union-busting, such allegations only scratched the surface.

Despite its troublesome place in the public eye, the Pinkerton Detective Agency remains a fascinating, mystifying chapter in America’s rich history. From its early founding and its notable achievements to its deep and troubled controversies, the lasting mark it has had on American history is undeniable.

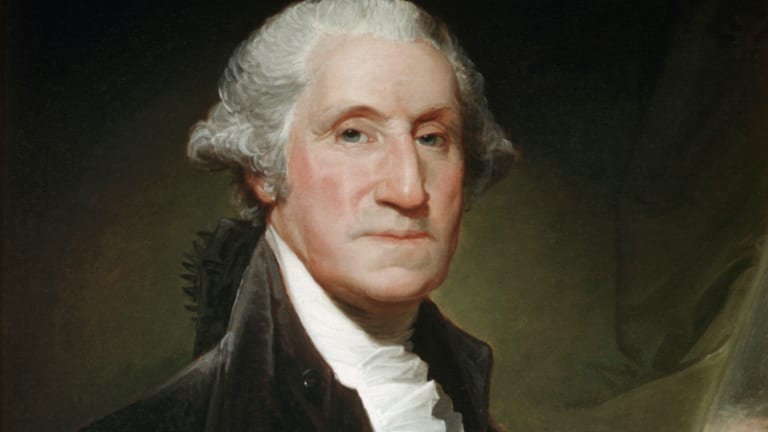

Who Was Allan Pinkerton?

Allan Pinkerton was born in Glasgow, Scotland in 1819. From a very young age, his natural talents and intellect were quite clear. After leaving school at the early age of just 10 years old, Pinkerton would find his place as a cooper – a cask or barrel-maker.

He wouldn’t stay put in Scotland, however. In 1942, Pinkerton emigrated to the United States. He first settled in Chicago before building a cabin and starting a cooperage in Dundee, a short way outside the city.

Pinkerton was also an early abolitionist. He was volunteering for Chicago abolitionist leaders by 1844. His home was even a stop on the Underground Railroad.

His interest in justice didn’t stop there. Despite a lack of formal detective or police training, Pinkerton’s natural investigative instincts led him to uncover a gang of counterfeiters while exploring the woods around his town one afternoon.

He reported them to the local sheriff and had the group arrested. In return, Pinkerton was eventually appointed as the very first police detective for Chicago and even a special agent for the U.S. Post Office.

With newfound success in catching criminals, these roles would pave the way for the establishment of his agency, one that would change the course of American history.

Founding and Early Years of the Agency

Initially founded as the North-Western Police Agency, the organization was a joint venture between Pinkerton and a local attorney, Edward Rucker. The two men saw the need for a private detective agency and founded the business in the early 1850s.

Early on, the agency worked with nearby railroads, protecting trains and apprehending train robbers. By February 1855, the agency expanded to working with multiple midwestern railroads and providing private detective services to other businesses.

It wasn’t long before the agency would come to be known by its infamous name – Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency.

A multi-talented figure, Pinkerton was able to use his skills in espionage and connections in law enforcement to grow the agency and add to its clientele. Already by the late 1850s, it had fifteen ‘detectives’ working a variety of cases.

However, these were just the early days for Pinkerton and the Agency, which quickly swelled in size and influence in the coming years.

The Civil War and Protecting Lincoln

Already an established abolitionist, Pinkerton and his band of detectives would come to play an integral role throughout the American Civil War.

The Pinkerton Detective Agency grew in size, influence, and notoriety before the outbreak of the Civil War. When the war began, Pinkerton was picked to serve as the head of the Union Intelligence Service.

He stayed in the role for two years, providing intelligence and Confederate troop counts to General McClellan, who was the commander of the Army of the Potomac.

Pinkerton’s agents were often the source of this intelligence. Throughout the Civil War, they were dispersed among the Confederates, disguised as soldiers and sympathizers. Pinkerton did the same, going undercover as a “Major E.J. Allen” in the Confederate Army, barely escaping alive after his cover was blown.

Most notably, the Pinkerton Agency played a significant role in protecting President Abraham Lincoln during the war.

After discovering an assassination threat against him in 1861, Kate Warne, a Pinkerton detective, successfully ensured Lincoln’s safe delivery to the capital city through a variety of clever disguises and tactics.

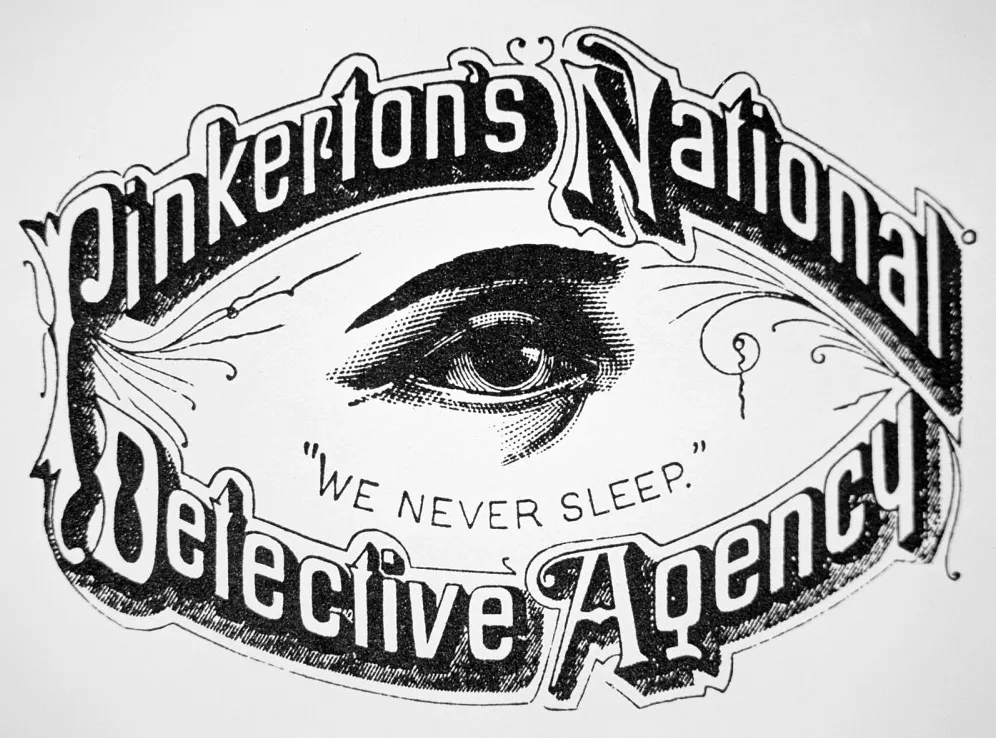

The business gained plenty of notoriety from this successful operation. Afterward, it adopted the slogan “We never sleep.” This referred to Warne’s need to remain awake for the entire trip, along with an open eye as its logo.

Tracking Down Criminals

After the Civil War, the Pinkerton Detective Agency grew in popularity and business exploded. The organization quickly was tasked with fighting all sorts of crime and hunting down outlaws.

They were hired by banks, express companies, and other businesses to deter robberies and protect valuable merchandise during transportation. Pinkerton agents were often hired to track down notorious outlaws such as Jesse James, the Reno Gang, and the Wild Bunch.

They never did catch Jesse James though. After a raid on the James farm went awry, Pinkerton opted to admit defeat and quit the chase.

Their job was dangerous, and many Pinkerton agents were killed in the line of duty. Despite the risks, they were typically well-paid and well-armed, and their success rate in tracking down criminals was high.

Infiltrating the Molly Maguires

Outside of chasing outlaws, the Pinkerton Agency also played a highly controversial role in the labor movement of the late 19th century. The organization and its agents were often hired by large companies as spies and occasionally as strikebreakers.

One of their most notable operations in this capacity was their infiltration of the Molly Maguires, which was a secret society of Irish American coal miners.

The Molly Maguires were active in both Ireland and the East Coast of the US. They were accused of causing all sorts of trouble, from organizing strikes and labor unions to supposed vigilante justice and murder.

The Pinkertons were called upon to infiltrate the group. One agent, James McParland, was successful. Daily, he gathered evidence which he then passed along to his Pinkerton supervisor, Benjamin Franklin.

Ultimately, his work led to the downfall of the organization. But it also served to solidify the Pinkerton Agency’s reputation as enemies of American labor.

Pinkerton and the Homestead Strike

Allan Pinkerton, the founder, and namesake of the prominent organization, passed away in 1884. He didn’t live to see his agency’s most infamous moments during the summer of 1892.

On July 6, three hundred agents from the Pinkerton Detective Agency, sourced from both of their offices in Chicago and New York, descended upon the Carnegie Steel mill in Pittsburgh.

They were hired by Henry Clay Frick. He was the chairman of the massive corporation. He hired the agency to protect the strikebreakers that were attempting to bring an end to the Homestead Strike. This was the mill workers’ attempt at procuring better wages.

Under the cover of night, the Pinkertons attempted to land at the mill. No one knows who fired first, but a deadly firefight and siege ensued in which many were killed or wounded.

When it was all said and done, the “Battle of Homestead” had been quelled. The Pinkerton agents surrendered, and an estimated nine strikers and seven agents were dead.

In the aftermath, the Pinkertons’ involvement in the Homestead Strike caused a national uproar and led to a crackdown on the agency.

National Outcry Leads to the Anti-Pinkerton Act

The Homestead Strike of 1892 and the involvement of the Pinkerton agents during the conflict led to a massive, national public outcry against the agency.

Congress quickly passed the Anti-Pinkerton Act in 1893. This prohibited the federal government from employing individuals from the Pinkerton Detective Agency or similar organizations. This severely limited the agency’s ability to work with the government and was a significant blow to the Pinkertons’ reputation and influence.

The Pinkertons were working with the government. They worked most closely with the Department of Justice for decades at this point. This new Act was a blow to business.

Despite this, the agency continued to thrive and grow. It succeeded in solving the assassination of Idaho Governor, Frank Steunenberg, in 1905. And it continued to track and catch outlaws across the nation.

Despite the backlash against them, by the time the 1920s rolled around, the Pinkerton National Detective Agency employed over 2,000 and was bringing in yearly revenues of around $2 million.

The Pinkerton Detective Agency in the Modern Age

The Pinkerton Agency’s reputation as a strikebreaker persisted through the 20th century, although they formally ended all anti-union work by the ‘30s. In more recent decades, they diversified their services into protection, risk management, and threat intelligence.

They even removed “detective” from their agency’s name in the 1960s. However, the firm no longer exists solely under the Pinkerton name.

The company was acquired by Securitas AB in 1999. They still acknowledge Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency as their forerunner, and the Pinkertons are now a subsidiary of their mother company.

They are also still active. In 2020, Pinkerton was hired by Amazon to monitor workers for union activity. In 2022, it was revealed that Starbucks hired a former Pinkerton employee for union-busting efforts.

Even today, the Pinkertons are staying true to their motto – “We never sleep.”

References

Bilansky, Alan. “Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency and the Information Work of the Nineteenth-Century Surveillance State.” Information & Culture, vol. 53, no. 1, 2018, pp. 67–84., https://doi.org/10.7560/ic53104. Accessed 1 Apr. 2023.

James, Jesse. “Allan Pinkerton’s Detective Agency.” American Experience, PBS, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/james-agency/.

“Pinkerton National Detective Agency.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 21 Feb. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Pinkerton-National-Detective-Agency.

Wilson, Mark R. “Pinkerton National Detective Agency.” Encyclopedia of Chicago, Chicago Historical Society, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/2813.html.