Last updated on January 27th, 2023 at 04:32 am

Undoubtedly one of the things that the Romans were most famous for was their baths. Unlike nearly all earlier civilizations that the archaeological evidence suggests were not overly concerned with personal hygiene, the Romans gave over large spaces in every city and town they built to public spaces where people could go and clean themselves.

As such, the residents of the Eternal City were the first people to invest large amounts of state resources into public sanitation and equate cleanliness with civility. But were the public baths effective at keeping people clean, and what was hygiene like in ancient Rome?

What were the Roman Baths Like?

Let’s start with the baths themselves. Though we call them Roman baths today, these went by two slightly different names at the time, depending on where one was in the baths. The parts of the baths where one steamed oneself, the equivalent of what we would call a sauna today, were known as thermae from the Greek thermos for ‘hot’.

The actual bathing chambers or baths were the balneae from the Greek balaneion, which means something close to ‘a place to bathe’.

There are numerous examples of Roman baths which are still largely extant today, the most famous being the Baths of Caracalla in Rome, built by an early third-century AD emperor, and the famous baths of the town of Bath in south-western England.

Almost every central town in the empire had at least one public bath, while many cities had multiple such cleaning facilities. The wealthy would have had private baths on their estates or villas. But despite their proliferation of them, the Roman baths did not necessarily create a clean society.

Water was only changed daily in many instances and without proper filtration systems such as those existing in modern public swimming pools. So whatever came off of one person stayed in the water for hours. As such, the waters of the baths became petri dishes of bacteria and disease as the day went on.

This fact was compounded by the fact that Roman physicians and doctors often prescribed ‘taking the hot waters’, i.e. spending large amounts of time in the thermae steam rooms as a curative for many ailments.

Consequently, sick people were often actively encouraged to go and spread whatever they were carrying in the local public baths.

Moreover, one of the practices in the public baths was to use scraping devices to scrape a person’s skin clean after being in the thermae, a practice that spread bacteria and germs even further.

All in all, while historians agree that the Romans’ obsession with cleanliness constituted a mark of social progress, there were many drawbacks to how they attempted this in the public baths.

Roman Public Toilets

This contradiction was mirrored in other areas. For instance, the Romans were one of the first civilizations to systematically build latrines or public toilets in their towns and cities. They even constructed them in military forts and other smaller settlements.

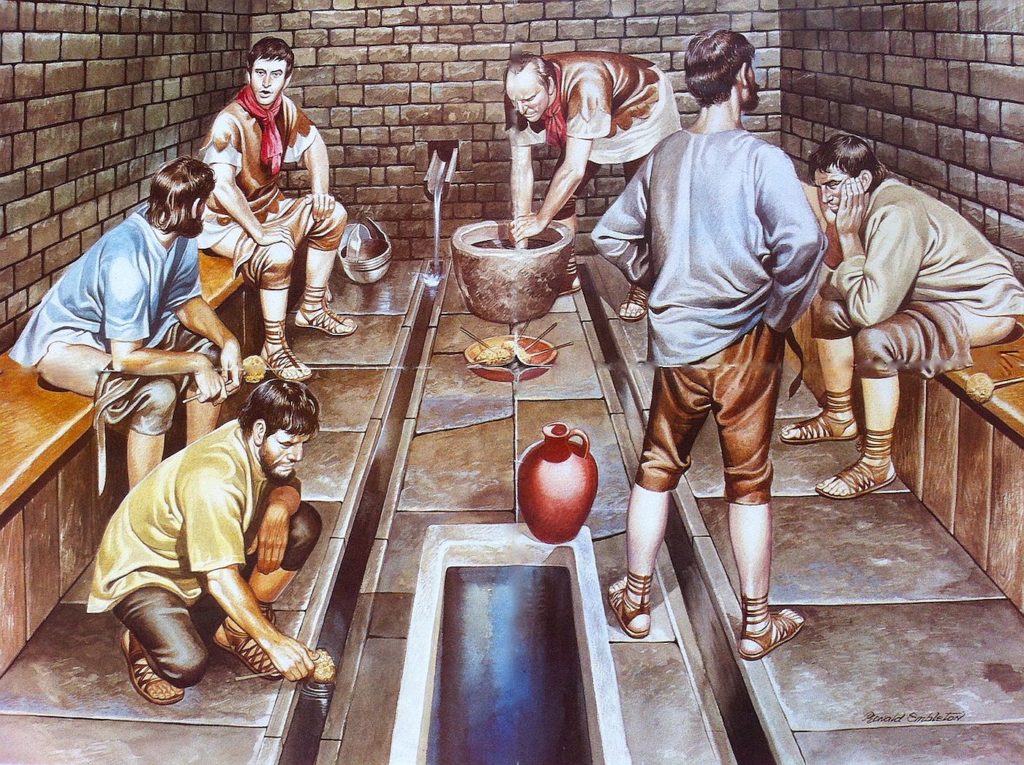

Often these consisted of large trenches over which something reasonably similar to modern public toilets were built, with seats of wood or stone that people sat on. A water supply was piped in to keep the waste below running through the trench to a less offensive place.

While this was not as effective as a modern sewage system, it had the same fundamental basics to how it operated. However, most homes were not connected to this system.

The waste that most people collected in pots was often thrown out on side streets and alleyways, as it was throughout Europe in more modern times until as recently as the nineteenth century in many large urban centers.

Unfortunately, one very unpleasant aspect of the public toilets was that the Romans used a device called a tersorium to clean themselves. This resembled a modern toilet brush and was effectively a sea sponge connected to the end of a stick.

Visitors used it repeatedly to clean themselves and wash in a bucket with water, salt, or vinegar between users. As well as being disgusting, this was highly unsanitary from a health perspective.

Disease from Hygiene

Other elements of Roman life were severely unhygienic, not by accident or ignorance of how sanitation worked, but simply through neglect. For example, although Rome made efforts to organize public rubbish collection services, the streets of Rome and other cities, particularly in the poorer districts, were often covered in rubbish.

This was largely food and household waste. So thick was it that stepping stones sometimes had to be put down to traverse especially affected areas. Unsurprisingly, rodents and other vermin were rife, as they often are in cities with current waste disposal problems.

More pedestrian ways disease might spread were through poor food hygiene or simply by even water puddles on damaged streets during winter. These could become spreaders of diseases like malaria.

Because of this, much like most societies until the late nineteenth century, Rome was prone to major disease outbreaks, notably the Antonine Plague of 165 AD to 180 AD.

This was probably a pandemic of smallpox or measles exacerbated by the cramped, unsanitary conditions of the empire’s cities. It killed between five and ten million Roman subjects, approximately 10-15% of the empire’s population at the time.

How Aqueducts affected Hygiene

One of the significant advantages that the Romans did have was a near-constant supply of fresh water for cleaning and drinking. In addition, their aqueducts, the large arches bearing pipes and conduits for water from rivers and other sources into towns and cities, were fantastic inventions that delivered water into the empire’s cities.

Without aqueducts, hygiene across the Roman Empire would have been far worse than it was.

Romans could clean themselves better, acquire fresh drinking water and at least keep sewage, bacteria, and germs manageable in cities like Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch, which had hundreds of thousands of inhabitants.

Indeed, it was not until the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that complex waterworks began being developed for cities like London, Paris, and Amsterdam that the Roman aqueducts were surpassed in their ability to deliver fresh, clean, safe water into European countries’ cities. So, while the Romans might have gotten many things wrong regarding their hygiene, they got an awful lot right too.

Sources

Fikret Yegül, Baths and Bathing in Classical Antiquity (New York, 1992).

M. Bradley, Rome, Pollution and Propriety: Dirt, Disease and Hygiene in the Eternal City from Antiquity to Modernity (Cambridge, 2012).

Harold Farnsworth Gray, ‘Sewerage in Ancient and Mediaeval Times’, in Sewage Works Journal, Vol.12, No. 5 (1940), pp. 939–946;

James McDonald, ‘The Health Risks of Living in Ancient Rome’, JSTOR Daily, 26 February 2016; J. F. Gilliam, ‘The Plague Under Marcus Aurelius’, in American Journal of Philology, Vol. 82, No. 3 (July 1961), pp. 225–251.

C. Bruun, The Water Supply of Ancient Rome: A Study of Roman Imperial Administration (Helsinki, 1991).