Last updated on July 21st, 2022 at 11:22 pm

The Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, which followed it controlled most of the Mediterranean world for over half a millennium.

That’s twice the length of the time that the United States has existed. At its height in the second century AD, Rome’s power extended from southern Scotland in the north-south to the Sahara Desert and even into Sudan and from the Atlantic coast of Morocco and the Iberian Peninsula eastwards as far as the Caucasus and Iraq.

There has never been an empire that ruled such a vast part of the world for longer than Rome.

Historians have argued many ways how Rome accomplished this. From its efficient bureaucracy and use of local elites to govern the provinces to its cultural sway with its road, amphitheaters, and aqueducts.

But when it comes down to it, Rome’s built its power with military might.

Moreover, this was not just about the sheer numbers of men it could deploy, but the discipline of its troops and the tactics employed on the battlefield.

The Roman Legion

The Roman army went through different stages. For much of the Republican period, when Rome was becoming the predominant power in the Western Mediterranean and expanding into the Eastern Mediterranean, its forces were not comprised of professional soldiers but were conscripted from the Roman citizenry.

Moreover, these had inherited many established military methods that had emerged in Greece in the fifth century BC.

These same methods allowed Alexander the Great to build his vast empire from Greece to India in the 330s and 320s BC.

This consisted of using hoplite soldiers with extremely long spears who went into battle using the phalanx formation.

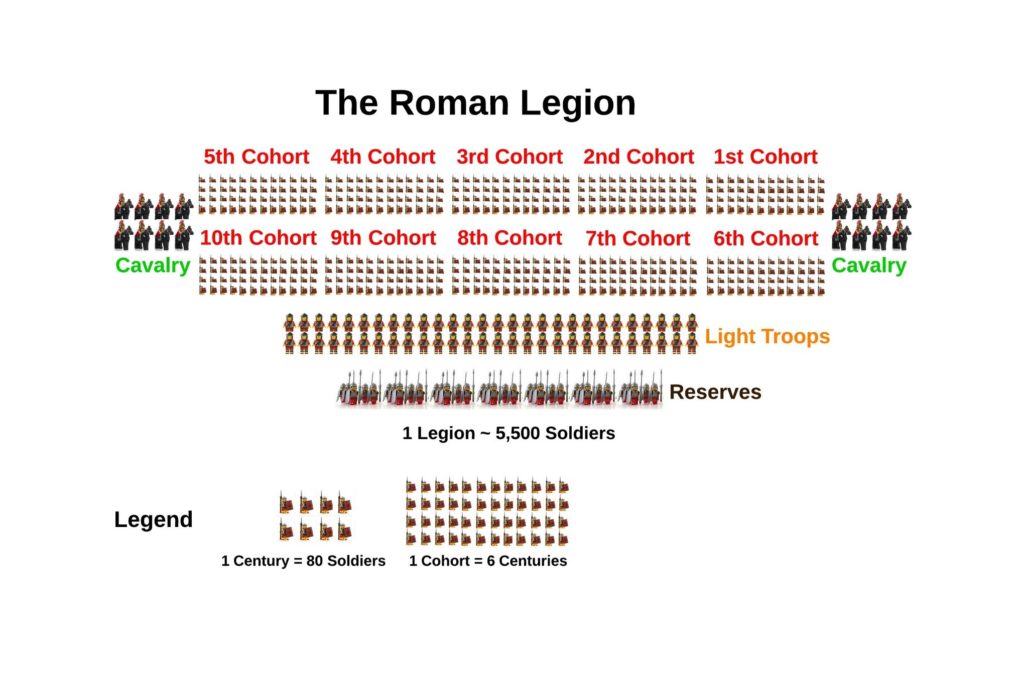

But from the second century BC, the Romans began developing the system of legions for which they have become famed—this involved divisions of legionaries consisting of approximately 5,200 infantry, complemented by 300 cavalry.

The legionaries carried heavy, rectangular tower shields known as scutum. Men were armed with a sword called a gladus and two javelins.

Thus, the weapons being used were fundamentally different from what the Greek hoplites of old used.

These legions, in turn, were divided into cohorts of approximately 480 men. Each was then sub-divided into six centuries of 80 men commanded by a centurion.

These individual centuries and cohorts each deployed tactics that fit in with the broader actions of the legion.

On the battlefield of battle, the commander of a cohort or century could direct his men, but they were all acting as part of a broader tactical system across the battlefield.

Roman Battle Formations

When a Roman army met an enemy in battle, they could line up in different ways.

One popular arrangement was the wedge formation, whereby a solid line of soldiers would spread out across the battlefield, but there would also be a concentration of force in the center in a wedge or triangle-like formation.

The goal here was to advance and penetrate the center of the enemy’s lines, thus dividing their lines into two and sundering communication between the two parts of the enemy army on the battlefield.

Another formation employed the direct opposite of this. This involved the Romans concentrating the bulk of their forces on their lines’ left and right wings.

This formation would give the impression of a weak center. The idea was to attract the enemy to push into the center, trying to break the Roman lines.

If the enemy commanders fell for this, the cohorts in the weak center would fall back, while the stronger wings’ forces moved forward to begin surrounding the oncoming enemy.

Once they had fallen into the trap, a reserve force that was held out of sight would come forward to reinforce the weak center.

In this way, the Roman legions would surround the enemy force and gradually annihilate their trapped enemy using javelins and field ballistae.

There were several other tactical arrangements like these which could be altered into a variety of approaches depending on the terrain.

For instance, mountains and hills or lakes could be used to protect one wing so that another wing could be heavily reinforced before an assault.

The Testudo

Whatever formation the Roman legions adopted during an engagement usually employed a popular formation within individual centuries and cohorts.

This formation was known as the testudo or tortoise. This was a type of shield wall whereby a certain number of men would line up in a square formation. For instance, a century might line up in ten lines of eight men.

These would stand close, with the men on the front and side lines holding their shields abreast and facing outwards. Then the men away from the outer lines would hold their shields above their heads.

In doing so, the men formed an almost complete shell around their entire unit. They would then move slowly as one unit forward on the battlefield with their shield wall, creating a protective shell, much like a tortoise.

This protected them from arrows, javelins, and other projectiles which might be fired at them as they advanced. As a result, the testudo was widely used by the Roman legions. As a result, many historians of Rome’s wars, such as Plutarch and Cassius Dio, wrote extensively about it.

Engaging the Enemy

The testudo would protect the legions until they closed on the enemy. Then when they were close enough, they engaged the enemy.

But this was systematic, disciplined, and professional. There was no wild charge at the enemy lines once they were close enough. Instead, once they were close enough, the legionaries would throw their two javelins in formation at the enemy lines to kill as many of their opponents as they could from afar.

By the imperial period, large field artillery such as onagers and ballistae were being used to bombard the enemy lines from afar.

Once the javelins and ballista fire had weakened the enemy’s front lines, the legions advanced, drawing their swords, and close-quarters combat began.

It was usually bloody for any enemy, most of which had less disciplined and less well-equipped troops than those of Rome. Once the attack proceeded to a certain point, the Roman cavalry would begin to sweep in to finish off the enemy.

This system was highly effective. For instance, at the height of Rome’s military power in the second century AD, some thirteen legions and auxiliaries or just under 100,000 Roman soldiers confronted upwards of a million Germanic tribespeople across Central Europe in the Marcomannic Wars of 166 AD to 180 AD.

Though the wars lasted many years and proved difficult for the empire, by the time Rome emerged victorious in 180, it had defeated an enemy which outnumbered it by approximately ten to one. Such was the power of the Roman war machine and its military tactics.