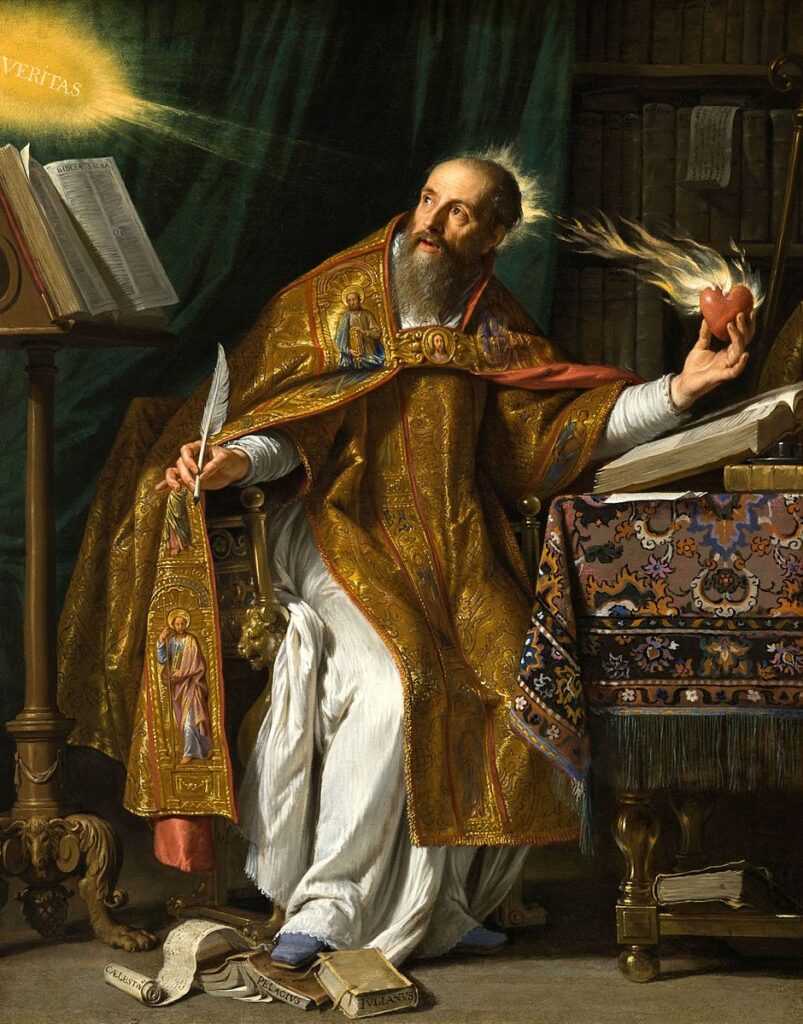

Saint Augustine is credited by many to be the greatest thinker of Christian antiquity. Today, he is credited with synthesizing the religious principles of the Bible and prevailing Greek philosophy.

He then presented it in a manner comprehensible to both medieval Roman Catholics and Renaissance Protestants. Ironically, however, in his time, Saint Augustine was considered only marginally important. He was a mere Church administrator.

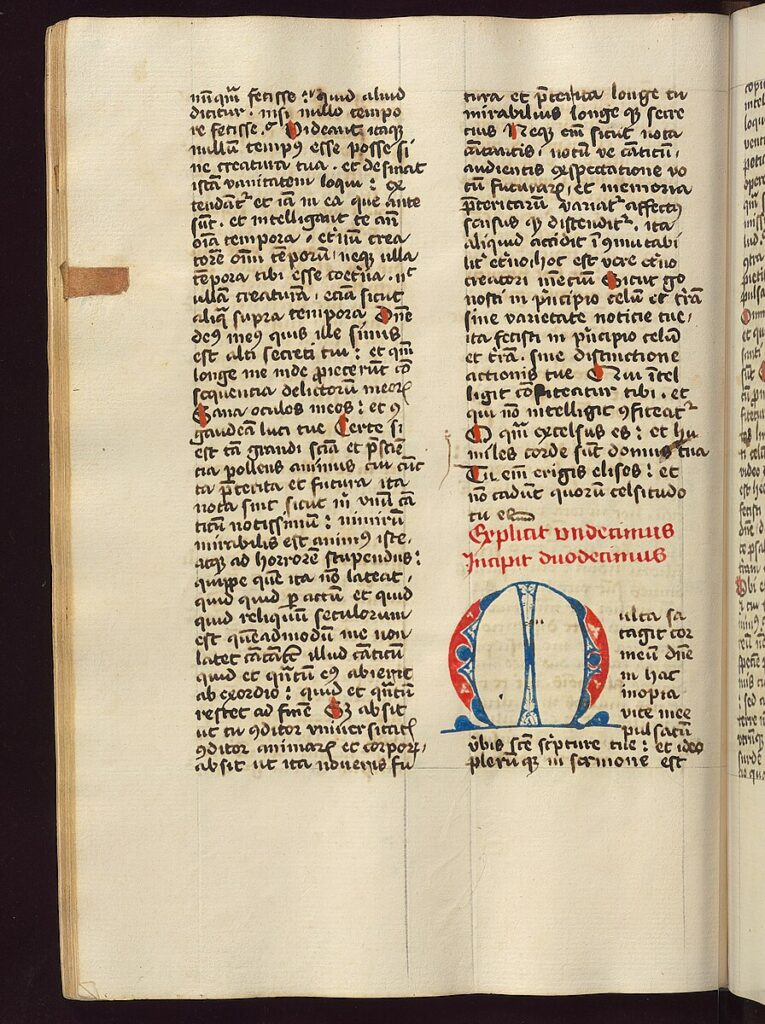

Thus, his unparalleled impact on Christianity came not from his standing in the Church, but from the 93 books, nearly 300 letters, and over 500 sermons he wrote. According to a long succession of prominent scholars, these are nothing short of brilliant.

Childhood

Saint Augustine (Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis) was born on November 13, 354 CE, in Thagaste, Roman Africa, to a middle-class Pagan/Christian family.

Few details are known about his parents. Saint Augustine’s father, Particius, was a minor landowner of the curial class (a class that held both civil and sacred responsibilities in Roman culture).

They held minimal wealth and limited social connections. His mother, Monnica, was a devout Christian who tried to instill in her son a reverence for “the name of Christ” from early childhood.

Although no reliable documents from Saint Augustine’s childhood survive, he is said to have been a relative “nobody.” He was dependent on the generosity of friends and more affluent landowners to provide financial resources

However, he demonstrated extraordinary intelligence and ambition even as a child.

Education

While the details of Saint Augustine’s earliest education are unknown, he is thought to have attended primary school in his hometown of Thagaste. Although the common language of Thagaste was Berber (an ancient language spoken in North Africa), there is no indication that he ever learned to speak it.

At age 11, Saint Augustine was sent to school at Madauros, a small Numidian city about 19 miles from his home. There he received the standard secondary schooling: familiarization with Latin literature, the Greek language, as well as a veritable pantheon of Pagan gods and beliefs.

Because of his apparent intelligence, his family hoped he’d find a career in government service.

At about the age of 17, Saint Augustine was sent to Carthage (in North Africa) to continue his education in rhetoric (the vocation of orators). This was financed largely by Romanianus, an older family member who held the title “flaman” (priest) in the dominant local Pagan sect.

Reason Over Blind Authority

Saint Augustine completed secondary school at Madauros. He also studyied rhetoric at Carthage. But to his mother’s disappointment, he chose not to follow Christian teachings.

Instead, he turned to the Manichaean religion (a Persian philosophy combining Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, and Jesus’ teachings). This is a religion based on reason rather than blind authority.

To the future saint, Christianity alone seemed much too illogical for any reasonable man to embrace.

He then discovered the Roman philosopher Cicero’s work, Hortensius. Saint Augustine described this as “leaving a lasting impression” and a desire to seek “the wisdom of eternal truth.”

He was left with an enthusiasm for philosophy, which to him equated with a devotion to the pursuit of truth.

Writing, Erotica, Manichaeism

At about 18 years of age, Saint Augustine began writing in earnest. His first writing was a melding of the Biblical Genesis “first sin” story and a chronicle of his own sexual exploits. These had begun at age 16 and involved a woman known as “Una” (a woman of low birth, and likely a prostitute).

Of this time, Saint Augustine wrote, “I came to Carthage, where all around me hissed a cauldron of illicit loves. As yet, I had never been in love yet I longed to love . . .”

A ravenous reader, Saint Augustine then began a study of “Manichaeism.” This was a religious system of materialistic dualism that claimed to be true Christianity.

According to Manichaeism, the world is the product of a primordial conflict between the forces of light and dark. These existed before the creation of the world.

The conflict was between these forces and the soul of man. Man was considered an element of the light entangled in the darkness. Manichaeism claimed that Jesus was the “redeemer” who would enable the imprisoned particles of light to return to their rightful realms.

While the highest order of the Manichaean Church was strictly ascetic and celibate (essentially monks), young men like Saint Augustine typically joined the lower order as a “hearer.” This was a position permitting marriage (and sex) as a “concession to human weakness.”

This concession no doubt appealed to Saint Augustine considering that he was living a wildly hedonistic lifestyle. He socialized with young men who boasted of their sexual conquests.

He maintained a number of sexual relationships, including one with the aforementioned, “Una,” with whom he would share a bed for 15 years. They also produced a son, Adeodatus.

Career, Activism, Authorship

At about the age of 20, Saint Augustine returned to Thagaste. There, he taught grammar at a small institute until 376 CE—while attempting to convert his students to Manicheism.

He then relocated to Carthage, where he worked as a freelance professor of rhetoric for the next several years. He cultivated a reputation as a Manichean activist.

In 380 CE, St. Augustine published his first book (now lost), called The Beautiful and the Appropriate. Though he continued to promote Manicheism cosmology, he noted that he doubted that the Manichean cosmic myths were in keeping with the emerging science of the day.

By 382 CE, the future saint was so disgusted by the disrespectful behavior of his students that he left Carthage for Rome. In Rome, he expected to find a more intellectual selection of students.

Rome

In 383 CE, Saint Augustine arrived in Rome with his mistress “Una,” son Adeodatus, and an entourage befitting his growing social status. Though increasingly disillusioned with Manicheism, he continued to align himself with Manicheism interests as it benefited him socially.

Finding Roman students no more engaged than their Carthaginian counterparts, Saint Augustine was considering yet another move. That is, until he met Quintus Aurelius Symmachus, a Roman senator recently appointed prefect (governor) of the city of Rome.

Charged with finding a professor of rhetoric (court orator) for the Imperial Court at Milan (residence of Theodosius the Great, Emperor of the West), Prefect Aurelius chose Saint Augustine to fill that position.

Court Orator, Milan

In late 384 CE, Saint Augustine assumed the most visible academic position in all the Latin world. This was at a time when such posts typically assured lucrative and powerful political careers.

As with other men of his status, he was provided a staff of slaves, stenographers, and copyists.

By this time, Saint Augustine had abandoned the doctrines of Manichaeism. He favored the materialistic trappings of his status.

This left him a spiritual skeptic with no satisfying way to remedy the philosophical questions tormenting his mind: the “being of God” and the “nature of evil.”

At this time, Ambrose, the Bishop of Milan (the most eminent Christian leader of the day) introduced the future saint to “Neoplatonic Mysticism.” This was a complex philosophy presented in the works of the Greek philosopher Plotinus (204–270 CE).

Though Saint Augustine found Neoplatonic Mysticism interesting, it was less than philosophically satisfying.

The Path to God

As Saint Augustine would later detail in Confessions, it was during an act of introspection that he (with certainty) found God. He called the “Changeless Light” at once “both immanent and transcendent.”

He immediately recognized as “the source of every intuitive recognition of truth and goodness.”

But to Saint Augustine’s dismay, finding God was more than just the conclusion of a process of reasoning, as he’d expected. Finding God was a mystical experience; vision and sensation that came . . . then mysteriously vanished.

Although finding God had been a fleeting experience, it nonetheless answered questions that had long troubled him.

While the Manichaeans were correct in believing that God is light and evil is darkness, he now understood the missing links: that the pure changeless “light of God is pure spiritual being” while “evil is non-entity; merely the absence of light.” To Saint Augustine, this revelation was life-changing.

But, why was the experience fleeting? Why was it not abiding? Then he had an epiphany:

He suddenly realized that he “had not yet made for himself the total identification” of the supreme value of spirit. He was still a “man of the flesh” who harbored sexual lust in his heart! The way to God must be through escape of the corporal body. He must escape the ties of sexual need.

In the spring of 387 CE, Saint Augustine was baptized by Bishop Ambrose. He then began severing ties from his former “lower” self.

Africa and Rome

After his conversion, Saint Augustine sent “Una” away, gave up his court post, and returned to Africa. He brought along his mother and a small group of friends. (On the ship voyage, Monnica died.)

Saint Augustine now felt that he had two specific duties: to expound the sphere of realization he’d discovered in finding God (in terms Christians could understand), and to refute other popular schools of religious thought. Both within and without Christianity.

Needing Rome’s vast library to further develop his arguments, Saint Augustine returned to Rome a short time later. For the first time, he found himself surrounded by Rome’s Christian community.

While there, the future saint finished the dialogue, “How to Measure the Soul.” He began “Freedom of Choice,” and completed the treatise, “Catholic and Manichean Moral Systems.”

This was all while maintaining a formal distance from the papacy. (He felt himself part of God, but not the Church.)

Completing his study, Saint Augustine set off for Africa. He settled in the port city of Hippo Regius, Numidia (modern Nigeria), where in 395 CE he established the first monastery.

While there, his path took an unexpected turn. Theologians believe had always been his destiny.

The Priesthood

Although it was common knowledge that Saint Augustine had never aspired to enter the priesthood, an event occurred that changed his intended course.

While praying in a church in Hippos, for a friend who’d sought his intercession, a number of people suddenly gathered around him. They began to cheer him.

They begged regional Bishop Valerius to initiate him into the priesthood. Though Bishop Valerius himself recognized Saint Augustine’s limitations in delivering Latin scripture, he nevertheless ordained him as an assistant priest.

In 396 CE Valerius died. Saint Augustine assumed his position as bishop.

But in 4th Century Roman Africa, a bishop was not just a pastor. He was also the presiding judge in a much-frequented court of summary jurisdiction in civil court cases.

Thus, in addition to crafting thought-provoking sermons for his congregation, a bishop was required to address any number of diverse philosophical and theological queries presented to him.

Confessions (The Testimony)

In 397 CE, Saint Augustine experienced an eruption of writing. Theologians liken this to an “implosion of his mind,” reflecting the deep introspection he was experiencing in his capacity as bishop.

Writing in an informal style quite unlike his sermons, the future saint began work on the 1st of 13 books that would constitute, Confessions (The Testimony). In this, he describes his growing relationship with God: “You were inside me, I outside me. [God was] deeper in me than I am in me.”

In Confessions, Saint Augustine declares that true knowledge of the soul’s nature can only be based on the “immediate deliveries of the self-consciousness,” and that the soul’s awareness of itself is of a trinity in unity which reflects “as in a glass darkly” the being of its “Maker.”

By the completion of the 13 books, Saint Augustine had presented all the themes that would dominate his later writings: time, memory, the inner dynamic of the self, the inner dynamic of God, and the continual activity of God in the soul.

These themes would ultimately establish him as one of the greatest thinkers in history. Ultimately, it is his perspectives on Grace, Free Will, Predisposition (and Sex) that came to define his brilliance.

Christianity in Perspective

To appreciate the impact Saint Augustine’s revolutionary ideas had on the Roman Catholic Church, it’s important to understand a few things. First, at the time of his birth, Christianity had only been a sanctioned religion for just over 40 years.

It had only been sanctioned since the time of Emperor Constantine I. It didn’t become the official religion of the Roman Empire until 380 CE (when the future saint was 26 years of age).

Accordingly, many concepts found in the Holy Bible and other religious texts (including Grace, Predestination, and Free Will) had yet to be de-mystified. They were considered unknowable by many Church authorities.

Thus, in addition to a bishop’s other congregational duties, his larger service to the Church was to meditate on the Bible’s mysteries and search from within to understand God’s mind.

More times than not, this led to heated arguments and divergence among the bishops. Some even devolved into personal feuds–even imposition of sanctions from superiors.

On the Subject of Grace

In traditional Christian theology, “Grace” is defined as the “spontaneous, unmerited gift of divine favor in the salvation of sinners, and the divine influence operating in man for his regeneration and sanctification.”

The Church typically refers to the “Letter of Paul to Titus” (2:11): “For the grace of God has appeared for the salvation of all men.”

This definition was accepted as early Catholic doctrine. However, Christian theologians were raising a myriad of technical issues regarding the relationship between God, mankind, and this “free gift.”

This necessitated the more elegant concept of actual Grace. That is, the relationship between human freedom and divine help.

In Catholic tradition, the Church has always maintained that the Grace of God is given to mankind. It is given not to make up for something lacking in human beings, but as a free gift that elevates us to a new and unmerited level of existence.

But, what exactly does that mean? And under what circumstances does that manifest? Those questions seem to have no definitive answers.

On the Subject of Free Will and Predestination

Typically, “Free Will” is defined as “the ability of agents to make choices free from certain kinds of constraints.”

In Christian theology, however, God is described as “omniscient,” “omnipotent,” and “omnipresent.” This implies that not only has God always known what choices individuals will make, He predetermines those choices.

So, if God knows exactly what will happen (and effectively predestines it), “Free Will” is nothing more than an illusion. God has already decided what we will do, think, and say.

Thus, Grace is undefined and Free Will is non-existent.

Saint Augustine’s Treatise on Grace, Free Will, Predestination, and Sex

Saint Augustine believed it incumbent on him to explain God in terms fellow clergy would comprehend. He drew comparisons to other religions/philosophies of the time (Stoicism, Manichaeism, Platonism, Donatists, Pelagians—among others), rather than speak hypothetically.

Like St. Paul, Saint Augustine believed that sin came into the world by one man: Adam. But he took the concept one step further.

He claimed that Adam’s “fall” from Grace meant that in all of us the “true order of love” has been violated. By the act of self-love, man departed from the love of God above and became subject to what is below.

Thus, “the subjugation of spirit to the flesh is a slavery the Will has no power to deliver itself from—and man cannot reverse the consequence of his fall by an exercise of Will.”

Saint Augustine wrote, “Men will not do what is right, either because the right is hidden from them, or because they find no delight in it . . . But that which was hidden may become clear, what delighted not may become sweet—this belongs to the grace of God which aids the wills of men.”

Essentially, “love means the overall direction of our Will (positively) toward God or (negatively) toward ourselves or corporeal creature,” (typically, in pursuit of sex).

Augustine insisted that without “delight in righteousness” there can be no true freedom in well-doing. There would only be servile obedience to law.

Accordingly, the love of God—which is the motive of Christian life—must be free.” Also while maintaining that “God alone is the cause of every human movement towards good”.

He then stated that “no event in time can alter the eternal setting of God’s Will toward any human soul,” which He chose “before the foundation of the world.”

God knows how each individual . . . “will respond to the particular form in which Grace is offered to him, and the elect alone receive the Grace that will win their acceptance.”

Interestingly, Saint Augustine believed that sex—as part of the “good human nature” created by God—would have occurred in Eden even if there had been no “fall.” He argued that “Jesus had semen and could have procreated if he had wanted to.

More so, Christ without virility [male sexual potency] would be without virtue. Christ’s flesh was perfectly responsive to the spirit—thus the question was not of capacity but of choice.”

The Final Years

On August 28, 430 CE, at the age of seventy-five, Saint Augustine (Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis) died.

Though scholars and theologians continue to debate Saint Augustine’s conclusions after nearly 1700 years, few are prepared to state that he was wrong.

(Note: St. Augustine was declared a saint before the official canonization process was instituted in the 12th century. He was declared a saint by those who knew him best and were familiar with his life and merits. The local bishop would then make the decision.)

References

betasparknotes,com., “St. Augustine,” https://beta.sparknotes.com/philosophy/confessionsaug/quotes/character/st-augustine/

gutenberg.org., The City of God, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/45304/45304-h/45304-h.htm

archive.org., Confessions: by Augustine, Saint, Bishop of Hippo, https://archive.org/details/confessions0000augu_k5u5

britannica.com., “St. Augustine: Christian bishop and theologian,” Saint Augustine | Biography, Philosophy, Major Works, & Facts | Britannica

www.ncronline.org., “Black Saints: Augustine,” Black Saints: Augustine | National Catholic Reporter (ncronline.org)

www.stgeorge-inn.com., “What’s in a Name: Who is St. Augustine?” History and Facts About St Augustine | St. George Inn (stgeorge-inn.com)

James, William. The Varieties of Religious Experience. New York: Barnes & Noble Classics, 2004.

plato.stanford.edu., “Saint Augustine,” https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/augustine/