In 1905, 37-year-old Sarah Breedlove, the first free-born child from a family of Civil War era slaves, moved to Denver, Colorado. She had just $1.05 in her pocket and was intent on starting a business selling hair-care products that she created, primarily for Black women.

Breedlove sold her products door-to-door. She would teach other Black women how to groom and style their hair in their homes.

By 1908, Breedlove was successful enough to open a beauty school and factory in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Two years later, Breedlove moved her business headquarters to Indianapolis, Indiana. This was a city with access to railroads for broad distribution and a large African-American population.

By the time of her death in 1919, Breedlove’s hair-care company, the Madame C.J. Walker Company, employed some 40,000 people. She had become the first independently wealthy female millionaire in American history.

Her net worth was in excess of $1 million. This is an estimated $18.1 million in 2023 dollars.

“Madam” Sarah Breedlove Walker is listed in the Guinness Book of World Records as the “First self-made American woman millionaire who didn’t inherit or marry into wealth.”

Early Life

Sarah Breedlove was born on December 23, 1867, near Delta, Louisiana, to Owen and Minerva (nee Anderson) Breedlove. They were a family of sharecroppers that included an older sister, Louvenia, and four brothers: Alexander, James, Solomon, and Owen Jr.

The Breedloves were the property of Robert W. Burney, owner of the Madison Parish Plantation. (The Breedloves had worked the plantation since before the American Civil War.)

Sarah, however, was born after President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This made her the first free-born Breedlove.

In 1872, Breedlove’s mother died, most likely from cholera. (A cholera epidemic traveled with river passengers up the Mississippi, affecting Tennessee and surrounding areas at that time.) Her father died a year later, making Breedlove an orphan by age seven.

At the age of 10, Breedlove moved to Vicksburg, Mississippi, where she lived with her older sister, Louvenia, and her husband Jesse Powell.

Expected to contribute to the family income, Breedlove began working as a domestic servant. To her advantage, after the abolition of slavery, there was a great demand for domestic help.

However, this left no time for formal education. A Sunday School literacy program organized by the National Association of Colored Women provided instruction on how to read and write.

First Marriage

In 1882, at the age of 14, Breedlove married Moses McWilliams who was an older man whose exact age is unknown. She did this to escape sexual abuse from her brother-in-law, Jesse Powell.

Breedlove and McWilliams had one daughter, A’Lelia (pronounced Ah-LEEL-ya), born on June 6, 1885. About two years later, McWilliams died—leaving Breedlove a widow.

(A number of records connect Breedlove with a man named John Davis–even suggesting marriage–but the details are unclear.)

Motivation

In 1888, 20-year-old Breedlove and her three-year-old daughter moved to St. Louis, Missouri. Three of her brothers worked at a barber shop.

She found work as a laundress. Although she rarely made more than a dollar a day, she remained determined to make enough money to provide her daughter with the formal education she never had.

Beginning in her teens, Breedlove had begun suffering severe dandruff and baldness: possibly alopecia. This was not uncommon within poor communities with frequent illness.

Many Blacks were forced to use harsh products for bathing and washing clothes. They had limited access to healthy foods and proper medication. Many accepted their situation as unchangeable.

But not Breedlove. Learning what she could from her brothers about hair care, she began experimenting with chemicals and household products, trying to find a cure.

Building a Career

About the time of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (“World’s Fair” at St. Louis, in 1904), Breedlove began working as a sales representative for Annie Turnbo Malone. This was an African-American hair care entrepreneur, and owner of the Poro Company.

Sales at the exposition had been disappointing since the African-American community had largely ignored it. So Malone gave Breedlove the option of hitting the streets with her products. (She, herself, had started her business by selling door-to-door.)

Then, while working for Malone, Breedlove continued experimenting with hair-care products based on what she’d learned from her three brothers. She was intent on developing her own product line for Black women, based on petroleum jelly and sulfur.

In July of 1905, the 37-year-old Breedlove and her 20-year-old daughter, moved to Denver, Colorado. There, she continued to distribute Annie Malone’s products—while moving ahead with her own hair-care business for Black women.

Next, to further her understanding of chemistry, she took a job as a cook to a local pharmacist who was happy to educate her.

A short time later, however, Malone accused Breedlove of stealing her formula (also based in petroleum jelly and sulfur). Breedlove argued that Black women had been using some combination of petroleum jelly and sulfur for generations.

Later the following year, Breedlove marketed her first hair-care product: a scalp conditioning and healing formula called, “Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower.” She used the name of the man she’d married earlier that year.

Charles Joseph Walker

In 1906, Breedlove again married. This time, it was to Charles Joseph Walker, a newspaper advertising salesman she met in St. Louis, Missouri.

While married to Walker, Breedlove adopted the name “Madam” C. J. Walker. This was a name she would use for the remainder of her life, particularly regarding her hair care business.

Similarly, her daughter assumed her step-father’s name, becoming, A’Lelia Walker.

Door-to-Door, Mail-Order, the “Walker System”

When Breedlove-Walker officially launched her hair-care product line, she marketed herself as “Madam” C. J. Walker, “independent hairdresser and retailer of cosmetic creams.” She is said to have adopted the title, “Madam” from the female pioneers of the French beauty industry.

Taking a page from Anne Malone’s strategy book, “Madam” Walker likewise sold her products door-to-door. But unlike Malone, she taught other Black women how to groom and style their hair in their homes.

In 1906, “Madame” Walker put her 21-year-old daughter in charge of the mail-order operation in Denver. Then, Walker and her husband traveled throughout the southern and eastern states to introduce Walker’s hair care line.

In 1908, Walker and her husband relocated to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. There, they opened a beauty salon and established Lelia College to train what Walker designated, “hair culturists.”

As an advocate of Black women’s economic independence, she then opened training programs based on the “Walker System.” This was for the national network of licensed sales agents she’d established (who earned handsome commissions).

By 1909, A’Lelia closed the mail-order business in Denver and joined her mother in Pittsburgh.

Indianapolis and Harlem

In 1910, “Madam” Walker established a new home base in Indianapolis, Indiana. She left A’Lelia to run day-to-day operations in Pittsburgh.

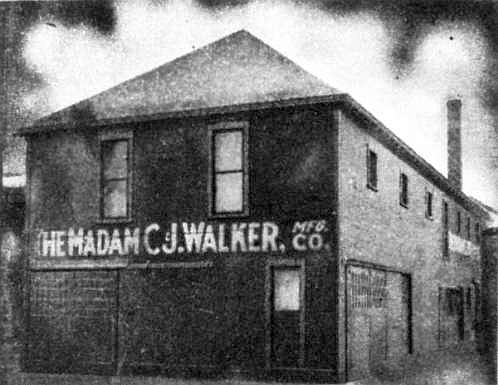

That same year, Walker established the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company in Indianapolis. She initially purchased a house and factory.

She then built a factory, hair salon, and beauty school to train her sales agents. Then, she added a laboratory to help develop better products.

Walker then assembled an experienced staff to assist in managing her thriving company. They included: an attorney, businessman, and civic activist Freeman Ransom to serve as legal counsel.

Also an attorney and civil rights leader Robert Lee Brokenburr to serve as General Manager. And lastly, a businesswoman, hair-care entrepreneur, educator, activist, and philanthropist, named Marjorie Joyner (to serve as advisor).

(Most of her company’s employees–including those in key managerial and staff positions–were women.)

In 1913, A’Lelia persuaded her mother to open an office and beauty salon in New York City’s growing Harlem neighborhood—the new center of Black “African-American” culture in America. Her salon became a cultural meeting place almost overnight.

Success, Expansion, Rivalry

Between 1911 and 1919 were the years that were the height of her business success. During this time, “Madam” Walker and her company employed several thousand women as sales agents (“hair culturists”) for its line of hair-care products.

By 1917, the company claimed to have trained nearly 20,000 women. All of them were required to know the Walker Beauty School manual.

Outside the factory setting, Walker’s agents focused on door-to-door sales. They visited homes around the US.

They gave out free samples of “Madam” Walker’s patented hair pomade and other products (packaged in tin containers carrying her image). In many cases, they demonstrated the products in their homes–as well as in neighborhood beauty salons.

By 1913, Walker was distributing her products throughout the Caribbean and Central America as well.

A shrewd businesswoman, “Madam” Walker understood the power of advertising and brand awareness. She advertised heavily (primarily in African-American newspapers and magazines like the Guardian and the Enterprise). She also made frequent personal appearances to promote her products.

By 1917, Walker and her line of hair-care products were phenomenally popular across the US, Caribbean, and Central America. Many competitors tried to copy her product formulas and sales model–including Annie Turnbo Malone.

In Support of Black Women Everywhere

Inspired by the founding of the National Association of Colored Women, in 1917, “Madam” Walker decided to use her considerable clout and celebrity for the betterment of Black women everywhere.

In addition to training in sales and personal grooming, Walker showed other Black women how to budget their money, start their own businesses, and become financially independent.

In 1917, “Madam” Walker began organizing her sales representatives into state and local clubs. The result of which was the establishment of the National Beauty Culturists and Benevolent Association of Madam C. J. Walker Agents.

In the summer of that year, the Association held its first annual conference, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, drawing 200 attendees. The conference is believed to have been one of the first national gatherings of female entrepreneurs to discuss business, commerce, and networking.

During the conference, “Madam” Walker distributed prizes to those women who sold the most products and brought in the most new sales agents. She rewarded those who made the largest charitable contributions to their communities.

Activism and Philanthropy

As “Madam” Walker’s wealth and notoriety grew, she became more vocal about her views. Particularly as the first freeborn Black woman from a family of slaves. She also became more active in contributing to the Black community.

In 1902, Walker helped raise funds to establish a branch of the YMCA in Indianapolis’ Black community. She pledged $1,000 to the building of Senate Avenue YMCA.

Throughout the first 50 years of its existence, the Senate Avenue YMCA branch had the largest membership of any African-American YMCA in the US. Membership climbed from 17 in 1904 to 3000 during the 1940s.

Major Contributions

Between 1912 and 1919, “Madam” Walker contributed a large portion of her wealth to a dozen or more worthwhile projects:

- Paid the tuition for six Black students at Tuskegee Institute

- Contributed to Indianapolis’ social services organization, Flanner House

- Funded Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church (the city’s oldest African-American congregation)

- Contributed to Mary McLeod Bethune’s Daytona Education and Industrial School for Negro Girls, in Daytona Beach, Florida (which later became Bethune-Cookman University)

- Provided grant money to the Palmer Memorial Institute in North Carolina (a preparatory school that more than 1000 African-American students attended between 1902 and 1970)

- Contributed to the Haines Normal and Industrial Institute, in Georgia (which housed the Lamar School of Nursing).

Additionally, Walker provided personal funds to preserve Frederick Douglass’ home (the former slave who became the first Black US Marshal) in the Anacostia neighborhood of Washington, DC.

In 1912, “Madam” Walker addressed the annual gathering of the National Negro Business League from the convention floor, where she declared:

“I am a woman who came from the cotton fields of the South. From there, I was promoted to the washtub. From there, I was promoted to the cook kitchen. And from there, I promoted myself into the business of manufacturing hair goods and preparations. I have built my own factory on my own ground.”

“Madam” Walker, 1912

The following year, she was given the honor of addressing convention attendees from the podium, as keynote speaker.

Death and Commemoration

On May 25, 1919, at the age of 51, “Madam” C. J. Walker died at her country home in Irvington-on-Hudson, Greenburgh, in Westchester County, New York. Though the official cause of death was listed as hypertension, she had, for many years, suffered high blood pressure and kidney failure.

Upon her passing, her daughter, A’Lelia Walker, became the president of the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company. Even after death, her thriving international hair care empire continued to expand. A’Lelia Walker continues her mother’s charitable work.

Eight years later, in December of 1927, Indianapolis’ Walker Manufacturing Company headquarters (renamed the Madame Walker Theater Center) opened. In addition to the company’s offices and factory, it included a theater, hair salon and barbershop, beauty school, drugstore, restaurant, and a ballroom open to the community.

In 1980, the Center was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Befittingly, perhaps, on January 31, 2022, Sundial Brands, a division of Unilever, launched a collection of 11 new products under the brand name, “MADAM,” by Madam C. J. Walker, sold exclusively at Walmart.

References

charlotteobserver.com., “Who was Madam C.J. Walker? What you should know about the Black entrepreneur,” https://www.charlotteobserver.com/news/business/article272843755.html#storylink=cpy

ndyencyclopedia.org., “Senate Avenue YMCA,” https://indyencyclopedia.org/senate-avenue-ymca/

https://madamcjwalker.com., THE OFFICIAL WEBSITE OF MADAM C.J. WALKER,” https://madamcjwalker.com/

https://madamcjwalker.com., “A’LELIA WALKER: A BRIEF BIOGRAPHICAL ESSAY,” https://madamcjwalker.com/about-alelia-walker/

britannica.com., “Madam C.J. Walker,” Madam C.J. Walker | Biography, Company, & Facts | Britannica

womenshistory.org., “Madam C.J. Walker,” Madam C.J. Walker | National Women’s History Museum (womenshistory.org)

blogs.loc.gov., “Madam C.J. Walker,” Madam C.J. Walker | Headlines & Heroes (loc.gov)

indianahistory.org., “Madam C.J. Walker,” Madam C.J. Walker, (indianahistory.org)