Last updated on September 28th, 2022 at 10:30 pm

Throughout history, there is no shortage of instances where people have turned to mass slaughter to facilitate their political ends and remove rivals from the scene. Many of these are well known.

For instance, in 1934, Adolf Hitler purged the leadership of the SA, including the head of the paramilitary force Ernst Rohm, once he became convinced Rohm was a threat to his rule. This event has become known as the Night of the Long Knives.

In 1572 the government of King Charles IX launched a series of attacks on French Protestants to try to decimate the Protestant leadership during the French Wars of Religion in an action known as the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre.

But there was an earlier medieval precedent for such behavior. This event was the St Brice’s Day Massacre ordered by King Æthelred the Unready of England on the 13th of November 1002.

Æthelred the Unready and the Danish Problem in Medieval England

The Massacre must be viewed within the wider context of the politics of England during the Early Middle Ages. Since the late eighth century, the country had been experiencing raids by Viking war parties.

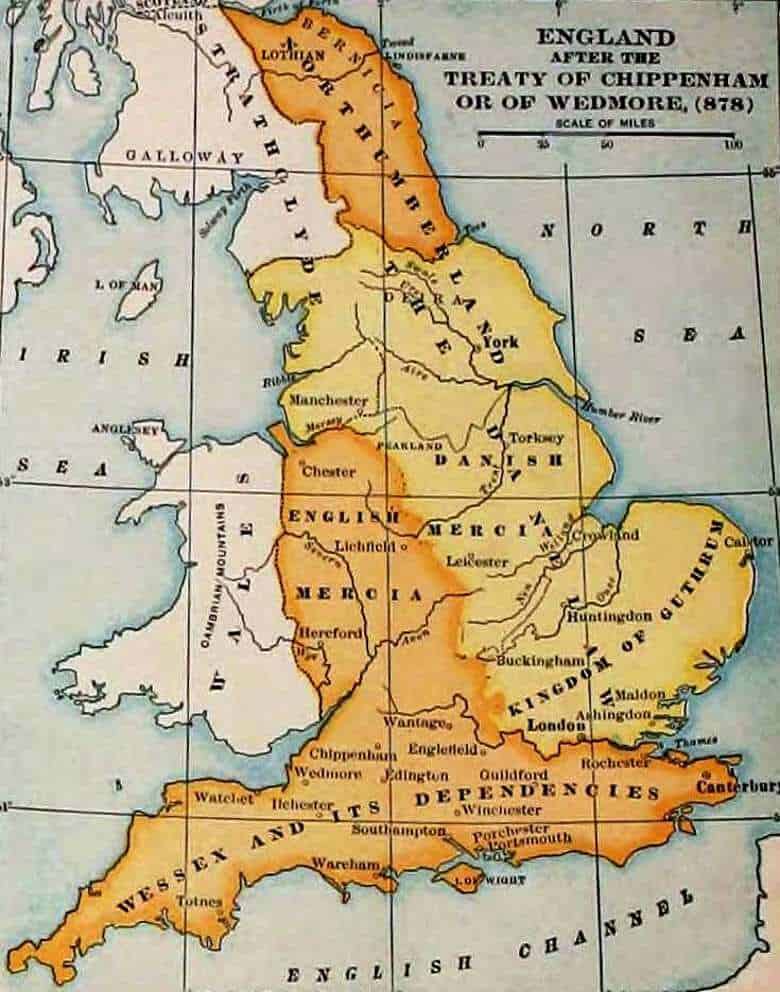

In England, these were typically referred to as the Danes. In the ninth century, they began settling in parts of northern and eastern England and carving out their principalities here.

Thus, by the tenth century, England was divided into two regions. The Danelaw in the north and east, and the Kingdom of Wessex in the south and west.

Eventually, following the reforms of Alfred the Great, the Kingdom of Wessex began to lay claim to all of England.

But the Danish threat remained significant, as the Danish lords in the north were periodically resupplied by their brethren in Denmark and Norway. This was the problem that Æthelred would face during his long reign between 978 and 1013.

Renewed Danish Attacks Around the Millennium

Danish raids on England increased in intensity during the last years of the first millennium. They took place every year between 997 and 1001, aided by the extensive provision of men and resources by Sweyn Forkbeard, the King of Denmark.

This was a particularly bloody period of European history as many people became convinced that the world would end on the one-thousandth anniversary of the birth of Christ. This millenarianism exacerbated the ferocity of the Danish attacks on England at this time.

To prevent these attacks from becoming too damaging, Æthelred was forced to begin paying the Danegeld again. This was essentially a payment of gold and goods paid to the leaders of Danish war parties to ensure that they would not attack Æthelred’s lands.

They had been paid frequently in the ninth century, but many kings of Wessex and then England had managed to strengthen their position to avoid having to do so. So now, Æthelred seemed to find himself back in the weak place his ancestors had been in before the days of Alfred the Great.

The St Brice’s Day Massacre

The massacre came about owing to two factors. Firstly, Æthelred and his advisors knew something needed to be done to strike back at the Danes. But, more significantly, they became aware in 1002 that there was a plan afoot amongst the Danes to try to take out Æthelred himself.

This spurred the English king to action, and the plan for the massacre was conceived. The king’s men would make their move on the 13th of November 1002, the feast day of the fifth-century French saint, Brice of Tours.

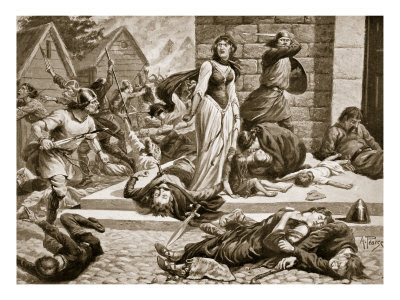

They would strike at Danes’ communities living anywhere on Æthelred’s lands and in the border areas. And they duly did this.

Unfortunately, our records for the eleventh century are so scarce that we cannot be sure how extensive the massacre which occurred was, but hundreds, if not thousands, of Danes were suddenly attacked in various places around southern, western, and central England on St Brice’s Day and massacred on Æthelred’s orders.

The Oxford Massacre

Clear evidence of one of the massacres seems to have come to light in recent years. In 2008 an archaeological dig at St John’s College in Oxford revealed a mass burial pit.

Inside, the remains of 37 people dating to the late tenth or early eleventh centuries were found, while further tests revealed that these people were of Viking descent.

Moreover, the abrasions and other damage to their skeletons indicated that these people had lost their lives in a brutal attack. Such was how their skeletons were damaged that it revealed many of them had been stabbed repeatedly while unarmed and presumably trying to flee from their assailants.

Given that Æthelred himself had referred to the part of the St Brice’s Day Massacre as having occurred at Oxford in a charter that he had drawn up in 1004, it seems fairly clear that the 37 skeletons found in this pit were the remains of a mass burial of dozens of victims who lost their lives on the 13th of November 1002.

Another mass burial pit located at Weymouth in Dorset can be dated accurately to between 970 and 1040. It contains the remains of 54 Viking males who were all beheaded, and this pit may also be associated with the St Brice’s Day Massacre.

The Danish Response

He was mistaken if Æthelred had intended that the massacre would destroy or at least weaken the Danish threat to his rule and life. In Denmark, Sweyn Forkbeard responded with fury, most likely because his sister, Gunhilde, and her husband, Pallig Tokesen, Ealdorman of Devonshire, were the victims.

Thus, he began launching annual raids against Æthelred and England in the following years. Moreover, since he had conquered Norway in 1000, Sweyn could now bring the armies of both countries to bear on England. Thus, after years of attacks, in 1013, Sweyn could drive Æthelred and his sons from England entirely and proclaimed himself the ruler of England.

His son, Canute the Great, was able to rule over Denmark, Norway, and England from 1018 to 1035 in what is known as the North Sea Empire. Consequently, while Æthelred had sought to protect his status as King of England through the St Brice’s Day Massacre, he ultimately ended up fatally undermining his position.