The subject of mental health has always carried aspects of social stigma, judgment, and harsh treatment for those struggling with their mental well-being.

While it is slightly less stigmatized today, there are still many misconceptions linked to mental health and wellness. During the 18th Century, mental hospitals were almost uniformly called asylums and were often places with terrible living conditions where families sent difficult children or spouses who may embarrass them with behavior that they couldn’t explain or control.

This period of poor treatment and a lack of understanding of the causes of mental health conditions has been popularized in a variety of ways through popular culture. Because of this, images of mental institutions carry with them very negative connotations.

However, by the 19th century, there were some important changes to the way that those suffering from mental illnesses were treated. These changes paved the way for improved care and understanding of those who lived with a variety of psychological conditions that we are now able to treat today.

Humanitarian Reform

The Enlightenment period, which was also known as the Age of Reason, began in the late 18th century. Increasing contact with people from all around the world, and writings from classic philosophers like Aristotle helped open the door to a much more enlightened way of thinking about social concerns.

While the early movers and shakers within this humanitarian movement were by no means liberal according to today’s standards, they were much more open-minded than those before them.

Chief among the thinkers in this movement was the philosopher John Locke, who wrote about religious tolerance and the need for governments to recognize the rights of the people.

Men and some women who were allowed to read such “scandalous” material began to absorb these new ideas about human rights and a social structure that was more humane in its treatment of its citizens.

The asylum system, as well as the poorhouse and workhouse institutions that had handled much of the treatment and sheltering of the poor and the mentally ill for generations, came under scrutiny during the Enlightenment Movement.

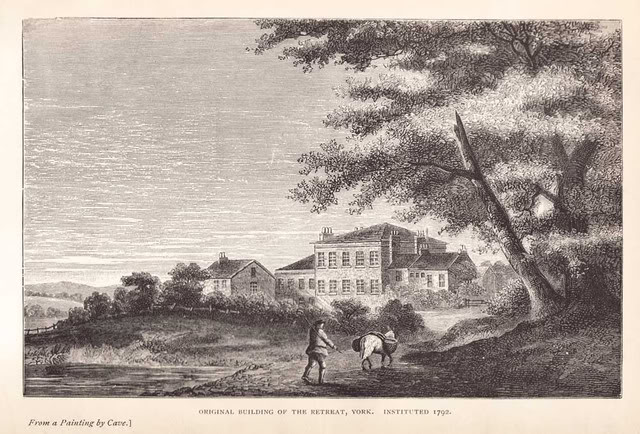

Already there had been some movement towards change in these institutions, such as the establishment in the late 1700s of a mental institution in York, England, called The Retreat.

This asylum was governed by the concept of moral management, which called for the reduced use of restraints and other forms of neglect and abuse that had formerly been believed to help “scare” mentally ill people into behaving properly.

Still, during the early part of the 19th century, many inmates at asylums died from being abandoned in straitjackets for hours or were forced to take heavy sedatives and other drugs in an attempt to control their behavior.

Some inmates were even lobotomized to try to “fix” their brains. Starvation and other forms of neglect were still very common in asylums until the 1930s.

Establishment of the Friends Asylum

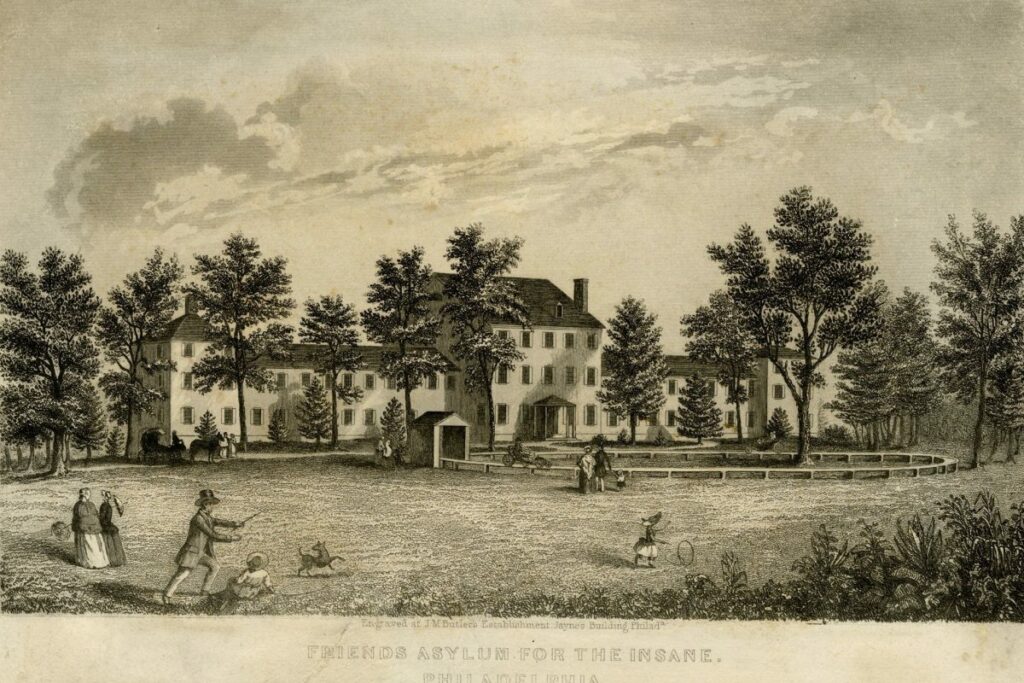

The Friends Asylum was opened in 1814 by Quakers in Philadelphia. This is one of the first examples of an institution that was run by people who were not doctors or nurses.

The program that this facility was built on was based on the concept of moral treatment, but the Friends Asylum took the concept much further than other asylums had to this point.

The method that governed the humane treatment of the patients at this location was built by Thomas Kirkbride, and so it became known as the “Kirkbride Plan”. Kirkbride called for a smaller population of patients, large open spaces that were light and airy, and private rooms that were made to be comfortable and clean.

Even more unique, the Friends Asylum was open to everyone, not just those who could afford to pay for their difficult family members to be hidden away from the sight of prying eyes. Poor and wealthy alike were allowed to reside at the Friends Asylum, something that was unique for its day.

Perhaps the most notable outcome of the establishment of the Friends Asylum was that it was funded, in part, by tax dollars. By the late 1890s, using the Friends Asylum as a model, many other countries created large systems of asylums that were funded by government money.

This proved to be a big turning point for the asylum and mental health movements. The government now held a stake in the management of these programs. Officials could no longer turn a blind eye to the treatment of those deemed mentally insane, old, or senile..

The Institution Era

With the government involved, most of the mental hospitals in the 19th century became more standardized in their treatment of patients.

There were still many problems regarding the treatments that were considered undesirable or inhumane for treating mental health. There were also lingering issues concerning the lack of training that was offered to the staff and the nurses who cared for the patients at these facilities.

However, the attitude around the discussions of mental health changed and headed in a more scientific and less stigmatized direction.

In 1845, The Lunacy Act was put forward by Lord Shaftesbury to attempt full legislation reform in Britain for the existing lunacy laws. This act provided for regular inspections of the institutions housing the mentally ill, and it created a body for asylum superintendents.

As with many social policies during this period, France and America followed closely in Britain’s wake with reforms of this nature.

However, despite the benefits of the many changes that had been made to the asylum system, the 19th-century public still loved a good spectacle.

Asylums were often opened to the public, and ticket fees were charged for people to come and wander the lush grounds and stare at the unfortunate patients who had not been asked if they were comfortable with this treatment of their privacy or not.

There were some small benefits related to the visibility of these institutions to the public, and witnessing the conditions at these asylums did help mitigate the fear of the “insane”. However, to modern sensibilities, the idea of treating a mental health facility as nothing more than a human zoo is quite offensive.

Women and Asylums

Women in the 19th century were offered almost no means by which they could support themselves outside of a husband. Other than taking dangerous jobs in factories, women of little to no means were not offered anything in the way of support. Wealthy women might have appeared to have much better lives, but that was not uniformly the case.

Women of all classes were treated much like possessions, bought and sold by the highest bidder and being able only to marry to improve their situation.

Women who were sound of mind were often placed in the asylum system if they became inconvenient to a husband or their family.

It was just as common for a woman who was not mentally ill to be committed to an asylum because of an inability to bear children. While there were, of course, women in these institutions who were suffering from mental health conditions, there were just as many female patients who had simply been discarded at the closest mental asylum.

Elizabeth Packard is a prime example of a female patient who was committed simply for disagreeing with her husband about religious matters. The couple had six children and had been married for years.

Packard had not displayed any symptoms of mental health struggles at the time that she was committed. She had only had her own opinion that differed from her husband’s, which was enough to see her committed to the state hospital.

Packard was clever and persuasive enough to take her case before a judge, and she was freed from the asylum and even allowed to divorce her small-minded husband.

She continued to fight for women’s rights for the rest of her life by becoming a lobbyist and an author. Many other women were not so resourceful or lucky, and they spent their entire lives in asylums with no hope of release.

The End of an Era

By the end of the 19th century, the moral rectitude and increasingly positive attitude towards the mentally ill that had started the reform of the asylum system was losing momentum.

Asylums were overcrowded, and it was hard to find the staff necessary to provide adequate care for the patients. Scandals involving patients and care providers were frequent, and the reform process had stuttered to a halt under the weight of limited funding and complex management needs that were not being met in state institutions.

Perhaps most damning of all, patients were not appearing to improve at the rates that had been expected when the reform process was begun. Many Victorians argued that if kindness did not help cure patients in asylums and the study of their conditions had not yielded any scientific breakthroughs related to curing mental diseases, why bother spending money and time on these people?

The Victorian era was a harsh one in many ways, full of social judgment, prudish dismissal of any difficult subject, and a strong belief that good morals and social acceptance cured all ills. The asylum system was set to enter another dark period which would stretch into the 1950s. Some of the changes that led to the closure of state asylums were well-intentioned, as those seeking to help the mentally ill tried to find new solutions to old problems.

However, abuse of the mentally ill, neglect, and disregard for their needs was once again the norm in institutions all around the world. One has only to learn the story of Rosemary Kennedy, lobotomized and dumped at a school for “exceptional children” in 1940, to realize that people of all social classes were still woefully neglectful of the mentally ill.

Nursing homes and new medications and treatments would eventually force the closure of most of the remaining asylums in the United States and Europe. Families were expected to keep their mentally ill members at home and provide them with love, support, and treatments that were available for their specific kinds of mental health challenges.

These changes went hand in hand with the rise of the modern healthcare system, which for all of its flaws, was a much-needed departure from the privatized and often exclusionary system that had existed before the 1950s.

Changes in Mental Hospitals Since the 19th Century

Today, there is no such thing as an asylum system in Europe or the United States. There are inpatient care facilities that can be accessed during periods when patients need round-the-clock care to be stabilized, but these are not homes for the “insane” or places where inconvenient family members can be dropped off and forgotten about.

Significant advances in mental health care have been made in the last fifty years, and there will doubtless be continued improvements in the care that can be offered to those suffering from mental health concerns.

The asylum period is a study of opposites. During some periods that the system was in place, real advances were made in the treatment of many mental health conditions, and there were efforts to humanize and understand the mentally ill. However, blatant abuse and disregard went hand-in-hand with the system and caused lasting damage to social groups and the healthcare field as a whole.

It Is important to look back on the history of the mental asylum as a warning about how easy it can be to compartmentalize that which we do not understand and shy away from things that are uncomfortable, to the detriment of large portions of the population who struggle with treatable illnesses, but who need the extra care and patience.

Sources

White, Matthew. “The Enlightenment.” The British Library, 21 June 2018, https://www.bl.uk/restoration-18th-century-literature/articles/the-enlightenment. Accessed 24 Feb. 2023.

Study.com. “Insane Asylums in the 1800s: History and Outlook.” https://study.com/learn/lesson/asylums-1800s-history-outlook.html. Accessed 24 Feb. 2023.

D’Antonio, Patricia. “History of Psychiatric Hospitals.” PennNursing, https://www.nursing.upenn.edu/nhhc/nurses-institutions-caring/history-of-psychiatric-hospitals/. Accessed 24 Feb. 2023.

Bazar, PhD, Jennifer L., and Jeremy T. Burnam, MA. “Asylum Tourism.” American Psychological Association, 1 Feb. 2014, https://www.apa.org/monitor/2014/02/asylum-tourism. Accessed 24 Feb. 2023.

Pouba, Katherine, and Ashley Tianen. “Lunacy in the 19th Century: Women’s Admission to Asylums in United States.” Wisconson.edu, 1 Apr. 2006, https://minds.wisconsin.edu/bitstream/handle/1793/6687/Lunacy+in+the+19th+Century.pdf;jsessionid=F23265A792DB87413440E2734349C94D?sequence=1. Accessed 24 Feb. 2023.

JFK Presidential Library and Museum. “Rosemary Kennedy.” JFK Presidential Library and Museum, https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/the-kennedy-family/rosemary-kennedy. Accessed 24 Feb. 2023.