The Mi’kmaq people are a large Algonquian First Nation tribe whose political influence and culture are still in effect today.

Though not as well-known as many of their neighbors, the Mi’kmaq people of eastern Canada and the northeastern United States have significantly impacted both nations’ history and the area’s culture.

These longstanding and influential people held strong political power that extends to this day and a culture that thrives on natural connection.

Here’s what you need to know about the Mi’kmaq people, both historically and in modern times.

Geographical and political history of the Mi’kmaq Tribe

The Mi’kmaq (also spelled Micmac or known as Mi’kmaw or L’nu) people are the largest First Nations community in what is now the eastern Maritime Provinces of Canada.

Their historical territory includes land in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island, with some extending into what is now Maine and Massachusetts in the United States.

Mi’kmaq people are part of the Algonquian-speaking groups of the area, though because their particular dialect is unique, it’s thought that they settled in the area slightly later than their neighbors. However, archeological research in the region has still determined their original settling was more than 10,000 years ago.

Mi’kmaq society had a loose central government structure that was primarily merit-based rather than hereditary and comprised of the leaders of individual small groups coming together to make alliances regarding the distribution of resources and interactions with other first nations. These leaders included wampum readers (also called putus) in charge of upholding the law and soldiers.

Beyond that, the Mi’kmaq lived in migratory groups of a few houses or families that congregated along rivers or the coast and stretched for many miles.

The Wabanaki Confederacy

The Mi’kmaq were a significant part of the Wabanaki Confederacy, alongside the Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, and Abenaki peoples.

The Wabanaki Confederacy actively interacted with early European colonizers in a slightly more peaceful manner than many of their neighbors until those settlements began expanding in the late 1600s and through to the settling of the United States and Canada in the late 1700s and early 1800s.

In the 1700s, the British moved into Mi’kmaq territory using the Treaty of Utrecht (without involving the tribe).

The Mi’kmaq people attempted to peacefully resolve the conflict by formally complaining to the French government and asking for their aid. However, the French told them they also claimed the land. Any Mi’kmaq claim would be ignored regardless of which European power claimed it.

Still, given their longstanding contact with the French, the Mi’kmaq supported them in the French and Indian War in an attempt to fend off British occupation.

This was unsuccessful, and in the late 1700s, the British claimed the land and began forcing the Mi’kmaq out of their territory. Over time, in much the same ways as their neighbors, the Mi’kmaq people were accosted by both aggressive settlers and invasive diseases they brought over, losing much of their traditional territory.

The colonizers slowly assimilated Mi’kmaq tribe members, and through modern times, the Mi’kmaq lost many of their original cultural practices.

Still, the Mi’kmaq people consistently held a place in the Wabanaki Confederacy and interactions with the American and Canadian governments. There are still members of the Mi’kmaq Grand Council serving as advocates for the Mi’kmaq people, striving to preserve and revitalize what they can of Mi’kmaq culture.

The Mi’kmaq lifestyle

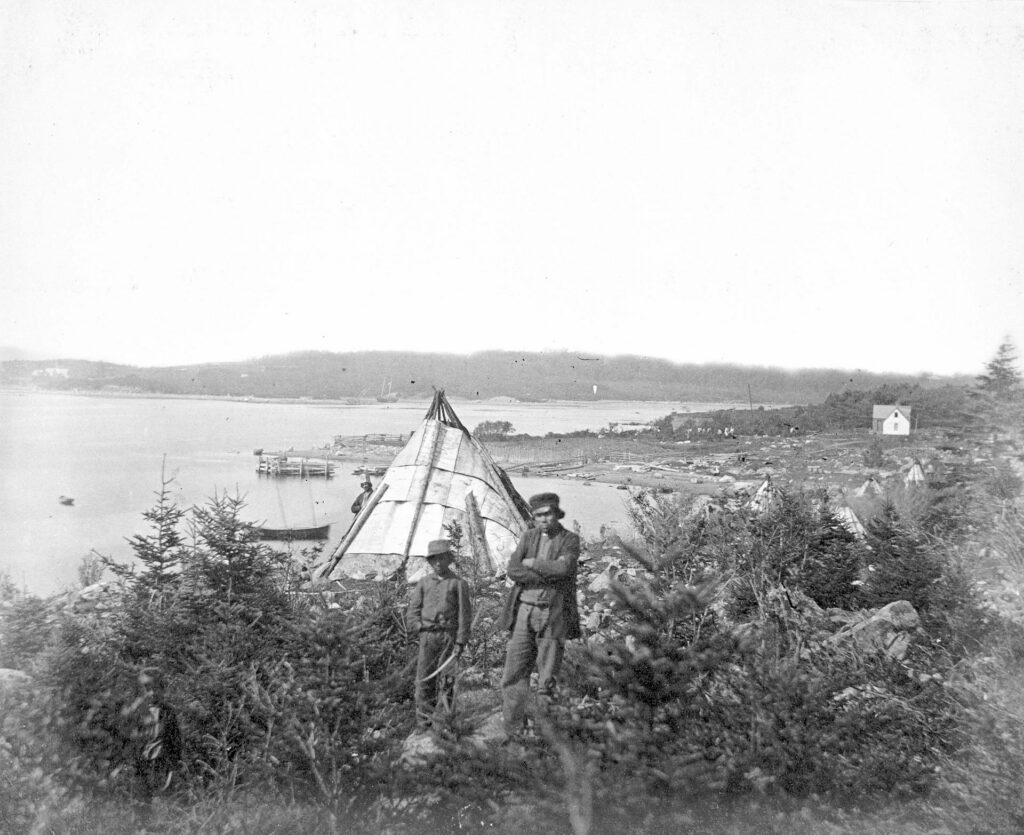

The Mi’kmaq lifestyle was historically nomadic, roaming their large territory to follow the animals they hunted for food and resources.

They stayed toward the coasts in the warmer months, hunting seals, fishing, and gathering shellfish, then moved inland during the fall and winter to hunt caribou, moose, and small game.

Their homes were wigwams, domed structures that used a framework of poles for support, made of various materials and construction methods suited to the weather (skins and bark in the winter, open-air in the summer).

Clothing in Mi’kmaq culture consisted mainly of thick fur and blanket robes with leggings in the winter and light loincloths or loose dresses or tunics in the summer.

These were usually decorated with fringes of hide, beads, or fabric and accompanied by moccasins and intricate beadwork. Peaked hats were common among Mi’kmaq women, though both men and women would wear beaded headbands adorned with feathers.

The Mi’kmaq language

The Mi’kmaq language contains both single- and double-letter constants and five vowels, which make both long and short sounds as they do in English.

Though pictographs have always been a large part of Mi’kmaq writing, Catholic teachers formalized the writing system into a semi-permanent alphabet in the 1600s.

The modern Mi’kmaq language has 17 unique dialects, which have become slightly blended over time, combined with English and French.

Mi’kmaq art

Mi’kmaq artwork heavily involved natural imagery and themes, expressing the deep connection the Mi’kmaq people feel to the world around them and the sense of responsibility they have for it. Rock painting is a traditional art form in the culture still practiced today, as is quillwork clothing and other textiles.

The Mi’kmaq religion

The Mi’kmaq people’s dominant religion revolved around a more general spirituality that involved The Creator, Mother Earth, and the original humans (the first of whom is a legendary figure known as Glooscap or Kluscap, who is said to have created the Annapolis Valley), who worked together to create the world they knew.

It came about in seven stages, which ended in the creation of the seven founding families of the Mi’gma’gi districts from the flames of the first fire.

According to this religious tradition, it was their responsibility to protect and live in harmony with the natural world. If they did so, the Mi’kmaq would continue to benefit from this world’s many resources and stay connected to The Creator (also called The Great Spirit).

Though this religious tradition was largely stomped out by Christian colonization and forced conversion, thanks to the work of Mi’kmaq advocates throughout the centuries, many Mi’kmaq still follows it today.

The Modern Mi’kmaq tribe

Today, the Mi’kmaq tribe totals around 170,000 people who live in and around Nova Scotia, Quebec, and Maine.

The modern Mi’kmaq society is proud to preserve and celebrate its culture and advocates for First Nations’ rights in the Canadian and American governments through online and in-person campaigns.

Modern Mi’kmaq artists and activists focus heavily on the nation’s interaction with the natural world, its beauty, and our duty to protect it, using traditional art forms like music, quillwork, and rock painting to express these values.

A particularly famous example of Mi’kmaq culture being largely influential is Emma Stevens’s 2019 cover of The Beatles’ “Blackbird,” sung in Mi’kmaq. Stevens, a Mi’kmaq teen, worked with her teachers, Carter Chiasson and Katani Julian, as well as her father, Albert “Golydada” Julian, to translate the classic song into their native language. Emma and several other students from Allison Bernard Memorial High School in Eskasoni First Nation, Cape Breton, recorded it.

This was done to highlight the threats to Indigenous languages that were brought before the UN that year. The cover became a viral sensation that was praised by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau of Canada and the original songwriter, Sir Paul McCartney.

The Mi’kmaq people have also had strong political challenges for their culture in Canada; as of 2022, Mi’kmaq as a language was recognized as Nova Scotia’s first language.

In 1999, the Supreme Court of Canada confirmed that the Mi’kmaq people (through activist Donald Marshall Jr.) were entitled to a “modern livelihood,” which included protected rights to hunt and fish on their own land regardless of seasonality.

This sparked a crisis between Indigenous and non-Indigenous fishermen that led to significant property damage to Mi’kmaq fishing vessels and equipment and was resolved (at least legally) with some government regulations on both sides. However, tensions continue to exist as the Mi’kmaq campaign for the right to their livelihoods and non-Indigenous fishermen campaign for equal access to their fishing grounds.

Beyond this, the Mi’kmaq people advocate against fracking and other environmentally damaging practices in their territory and continue to work to preserve their own culture and history as well as their claim to their ancestral land.

Learn more about the Mi’kmaq people

The Mi’kmaq people are a major player in advocacy work for First Nations people and the dedication to the preservation of native culture and language on the North American continent.

Their highly artistic and environmentally focused attitude has shaped the cultural landscape of their entire territory, even through colonization and directed efforts to stomp out native culture.

If you’re interested in learning more about the Mi’kmaq tribe, you can find them online here.

Sources

https://www.bigorrin.org/mikmaq_kids.htm

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Mikmaq

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/micmac-mikmaq