The 1950s and 1960s were the proverbial heydays for behavioral psychology experiments in the United States.

Harry Harlow’s Rhesus Monkey Experiments tested the effects of maternal separation and social isolation. The Solomon Asch Conformity Experiments tested the power of conformity in groups. Finally, the New York Child Development Center’s Child Development Twin Study examined the effects of twins raised apart.

These experiments provided what the psychological community considered invaluable insight into human behavior. But none proved more revealing than the Milgram Experiment, an ongoing experiment conducted from 1961 to 1963 to test our blind obedience to authority and indifference to human suffering.

Background Context for the Milgram Experiment

Amid the highly publicized trial of German Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann in1961, Yale Assistant Professor of Psychology Stanley Milgram set out to scientifically explain the psychology of genocide.

Eichmann, the primary perpetrator of the Holocaust, was captured in Argentina by Israeli operatives and taken to Israel to stand trial for war crimes.

His trial, which began on April 11, 1961, was televised and broadcast internationally, intending to educate the public about atrocities committed against Jews; these proceedings were second only to the Nuremberg trials in terms of “crimes against humanity.”

In that Eichmann did not accomplish these horrendous acts alone (and did not actually commit murder himself), Milgram set out to answer a few fundamental questions about human involvement in cruelty involving the taking of life.

Could it be that Eichmann and the million accomplices involved in the Holocaust were following orders, somehow making them less culpable? Or should they all be considered collaborators? More to the point, how far would the typical individual go to obey an order?

How Was The Milgram Experiment Designed?

Milgram designed an experiment whereby participants were told by a man wearing a gray lab coat (to assert his position as authority) that they were volunteering to be part of an experiment to test the relationship between punishment, learning, and memory.

They were told they would be randomly assigned to the role of either a “teacher” or “learner.” As a “teacher,” their job would be to ask the “learner” questions and then deliver increasingly higher voltage shocks depending on whether they answered correctly or not.

In reality, the “learner” was an actor paid to respond according to a script. The study was rigged so that every participant would be assigned the “teacher” role (the true subject of the experiment). The “learner” intentionally answered questions incorrectly—thus compelling the “teacher” to administer increasing levels of punishment.

Separated by a partition, the “learner” would protest, scream and eventually go silent as the shocks became more powerful. Of course, the shocks weren’t real, but the subjects were led to believe they were.

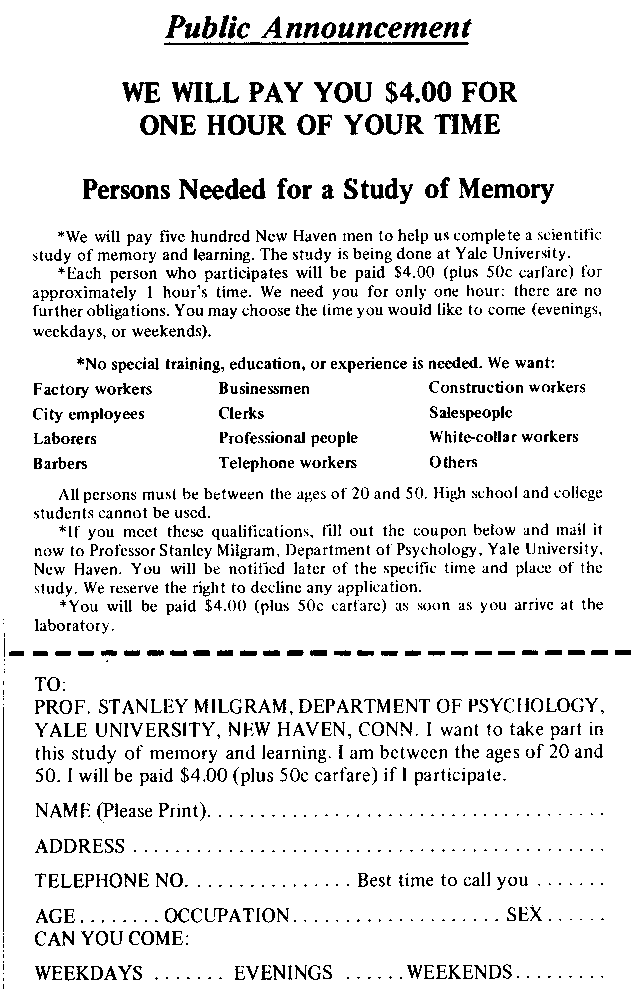

The sample group of participants was initially men between the ages of 20 and 50 from the New Haven, Connecticut, area. Still, as the number of male volunteers diminished, they also accepted women. In all, 780 volunteers took part in the experiment, 40 of which were women. Each participant was paid $4.50 for their cooperation.

The Experiment

Upon arriving at the Yale Interaction Laboratory, the “teacher” witnessed the “learner” being strapped to a chair and electrodes attached to his arms. Teacher and learner were then separated, unable to see one another, only hear.

The teacher was seated in front of a control panel that (supposedly) enabled them to administer 30 shock levels of pain, ranging from 15 to 450 volts.

Each shock level was clearly labeled, describing its effects. For example, “Slight Shock,” “Intense Shock,” “DANGER: Severe Shock,” and at maximum shock level simply, “XXX.”

The experimenter/authority figure sat behind the teacher, taking copious notes to emphasize the importance of the experiment. Then, so that each “teacher” would have some sense of the discomfort that they were administering to the “learner,” they were given a 45-volt shock before beginning—a bit more than slight.

“Teachers” were provided a list of questions they were to ask “learners,” a paired-association learning task the learner, of course, would intentionally answer incorrectly at prearranged times.

With each incorrect answer, “learners” supposedly received a more intensive shock.

Throughout the experiment, if the “teacher” hesitated to provide the appropriate shock, the conductor of the experiment would use one of 4 “prods” to assert his authority:

- Please continue.

- The experiment requires you to continue.

- It is absolutely essential that you continue.

- You have no other choice but to continue.

Meanwhile, the actor portraying the learner would provide appropriate reactions ranging from groans to yelps to screaming in agony; at higher levels, pleads to stop claims of suffering a heart attack–to dead silence.

Only after the experiment was completed was the participant informed that they were the true focus of the experiment.

Findings of the Milgram Experiment

Although the results varied across the participants, a disturbing number of “teachers” were willing to proceed to the maximum (XXX) voltage level despite pleas from the “learner” to stop and belief that they were administering dangerous—if not fatal—jolts of electricity.

Interestingly, 80% of those who balked at continuing after hearing the learner scream (at 150 volts) were nevertheless willing to proceed to the maximum of 450 volts once urged to do so by the authority figure.

Subjects displayed a wide range of negative emotions—some begging the conductor to stop the experiment–even as they continued to administer increasingly higher levels of electricity. One “teacher” who’d supplied maximum voltage was convinced they’d actually killed the learner.

Statistically, 65% (two-thirds) of the subjects/teachers continued to the highest shock level (450 volts), and no participant refused to continue at less than 300 volts, nearly seven times the voltage they had experienced.

Implications of the Milgram Experiment

Milgram concluded that based on these findings, most ordinary people are likely to follow orders given by anyone they perceive as an “authority figure,” even to the extent of killing an innocent human being if sufficiently prompted to do so. Furthermore, he believed that obedience to authority is ingrained in us all to various degrees beginning in childhood.

As a whole, people typically obey orders from others if they recognize their authority as morally right and/or based on legality (exemplified by those whose job is to execute prisoners for the penal system or participants in military firing squads). This is in response to what is deemed “legitimate” authority learned in various settings, including school, church, home life and family, law enforcement, military, and workplace environments.

Although many factors contribute to how far an individual is willing to go to obey an order given by an authority figure, the vast majority will commit to total involvement if the authority figure convinces them they have no choice.

References

SimplyPsychology.Org., “The Milgram Experiment,” http://www.edmotivate.com/uploads/4/7/6/4/47648491/milgram_experiment.pdf

Britannica, “Milgram Experiment,” Milgram experiment | Description, Psychology, Procedure, Findings, Flaws, & Facts | Britannica

De Vos, Jan, “Now that you Know, How do You feel? The Milgram Experiment and Psychologization,” file:///C:/Users/coffe/Downloads/Now_that_you_know_Arcp7devos.pdf