Last updated on December 17th, 2022 at 08:35 pm

There are a great many tales that have been disseminated down into popular culture, which were produced by the Brothers Grimm or the Grimm Brothers, as they are variously known.

Jacob Ludwig Grimm and Wilhelm Carl Grimm were German academics from the state of Hesse or Hessen in the late eighteenth and early-to-mid-nineteenth century, who are famous for collecting ancient folklore tales and stories from around Germany and adjoining areas.

Many of these stories had been transmitted throughout Germany and other areas for hundreds, and sometimes even thousands of years, but until the Grimms recorded them and published them, these stories had remained unavailable in print.

That all changed once they began printing these stories, ones like Hansel and Gretel known to all modern school children from the 1810s onwards. Some of these stories are famous, few more so than that the story of Rapunzel.

But what might have been the story and the anthropological elements which lay behind the true story of Rapunzel?

The Origins of Rapunzel

First, let us look at the story of Rapunzel itself. The story of Rapunzel was first published in 1812 by the Brothers Grimm in one of their first compendiums of tales entitled Children’s and Household Tales.

This was collected from some less well-known collections composed by eighteenth-century German folklorists such as Friedrich Schulz and tales which the Grimms had collected orally from individuals whom they met while traveling around Germany.

The plot of Rapunzel is complex. It begins with a couple living next to a large compound consisting of a vast garden and a tower belonging to a reclusive woman.

They have little to do with the woman, whom we later learn is a sorceress and who owns the tower and the garden.

But soon, the couple finds themselves drawn towards the compound as she becomes pregnant and begins to crave a type of salad green which they spot growing in the garden next door. This plant is generally believed to have been the Campanula rapunculus, a salad green known as the bellflower.

Bizarrely, the pregnant woman is adamant that she must eat some of the Campanula rapunculus even as she begins to lose weight, threatening the life of the unborn.

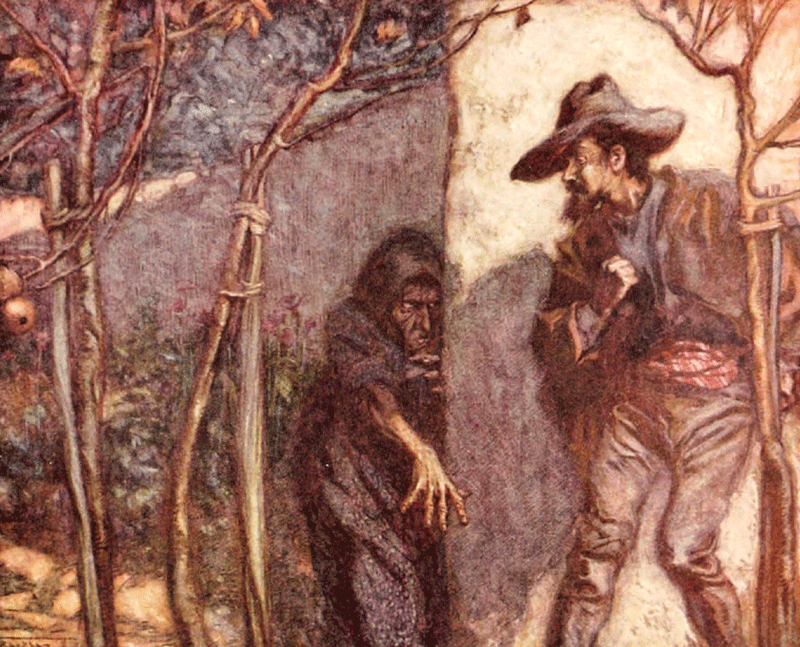

In despair, her husband agrees to break into the sorceress’s garden to obtain some of the bellflowers. And his first foray is successful. He scales the wall of the compound and finds some of the plants before returning home and giving them to his pregnant wife, but now she becomes obsessed with eating them.

In the days that follow, he repeatedly breaks into the compound to obtain more and more of the flower until one day, while he is escaping from the compound, the sorceress catches him. This act is the genesis of the myth of Rapunzel.

The sorceress now insists that the couple hand over their child when it is born as punishment for having broken into her garden.

They begrudgingly agree that the child is indeed handed over in due course when a baby girl is born. The sorceress names her Rapunzel after the plant which her mother was so obsessed with eating, and as she grows up, the sorceress locks her up in the tower within the compound.

There she grows up as a teenager with long golden hair.

Then, one day a prince comes through the area and hears Rapunzel singing from the tower. He is entranced by her voice and drawn to see what the source of it is.

Eventually, he manages to find his way into the tower, and he and Rapunzel fall in love. But they must navigate the ill demeanor of the sorceress, and although the prince attempts to explain the situation to her when he does, the sorceress cuts off Rapunzel’s hair. She casts her out of the tower and the compound altogether.

She is left to wander the wilderness, seemingly helpless, given that she has not known anything other than the tower and the garden for her entire life. When the prince returns and learns what has happened, he throws himself from the tower and is blinded.

He spends years thereafter wandering the wilderness, but eventually, the story has a happy ending. One day, as he is wandering blindly through the forest, they meet each other, having heard each other singing.

When they meet, the prince’s sight is miraculously restored, and he learns that Rapunzel has given birth to twins, a boy, and a girl, in the interim. The family heads back to the prince’s kingdom, where they live happily ever after.

Unlike many of the Grimm Brothers’ other stories, this one starts bleakly and ends happily.

So what exactly is the backstory to this? What might this allegory reveal?

Modern interpretations of the story of Rapunzel view it as being in line with a long line of maiden in the tower stories, which originated in Medieval Europe and became more popular again during the early modern period.

For instance, the story is essentially a German rendering of a French fairy tale called Persinette, written by Charlotte-Rose de Caumont de la Force and published in 1698.

This features all of the same elements of the tale of Rapunzel, including the prince, the tower, and a maiden with long hair. Moreover, the tale has wider origins stretching back to the late classical period, as much as 1500 years before the Brothers Grimm were writing and compiling their information, notably the tale of Saint Barbara, a third-century Christian martyr who is believed to have been imprisoned in a tower in Eastern Europe during the third century.

More widely, the tale of Rapunzel is indicative of the idea of a maiden in the tower, so much of which suffuses the folklore which was related in the Medieval and early modern periods, not just by the Brothers Grimm, but by other folklorists such as Hans Christian Andersen and which continues to be conveyed to modern audiences through Disney stories and many other mediums today.

Source

Maria Tatar, The Hard Facts of the Grimms’ Fairy Tales (Princeton, 1987); Donald Hettinga, The Brothers Grimm (New York, 2001); Ruth Michaelis-Jena, The Brothers Grimm (London, 1970).

On what follows, see Laura J. Getty, ‘Maidens and their Guardians: Reinterpreting the Rapunzel Tale’, in Mosaic: A Journal of the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature, Vol. 30, No. 2 (1997), pp. 37–52; Simon Hood, The Story of Rapunzel (London, 2019); Anna Wing Bo, ‘Losing Sight, Gaining Insight: Blindness and the Romantic Vision in Grimms’ “Rapunzel”’, in Advances in Language and Literary Studies, Vol. 10, No. 3 (2019), pp. 140–144.

Kathleen Rinkes, Translating Rapunzel: A Very Long Process (Calfornia, 2001).

Laura Christensen, Persinette: French Fairy Tales and Folklore Book 1 (Seattle, 2015); Hilary Crew, ‘A witch of a mother?: Rereading the Rapunzel Tale’, in Journal of Youth Services in Libraries, Vol. 14, No. 3 (2001), pp. 45–51.

Erin Graffy de Garcia, Saint Barbara: The Truth, Tales, Tidbits, and Trivia of Saint Barbara’s Patron Saint (Santa Barbara, California, 1999).

On the legacy of the story and the wider maiden in the tower tale, see Marina Warner, ‘After Rapunzel’, in Marvels and Tales, Vol. 24, No. 2 (2010), pp. 329–335; Kate Forsyth, The Rebirth of Rapunzel: A Mythic Biography of the Maiden in the Tower (New York, 2016).