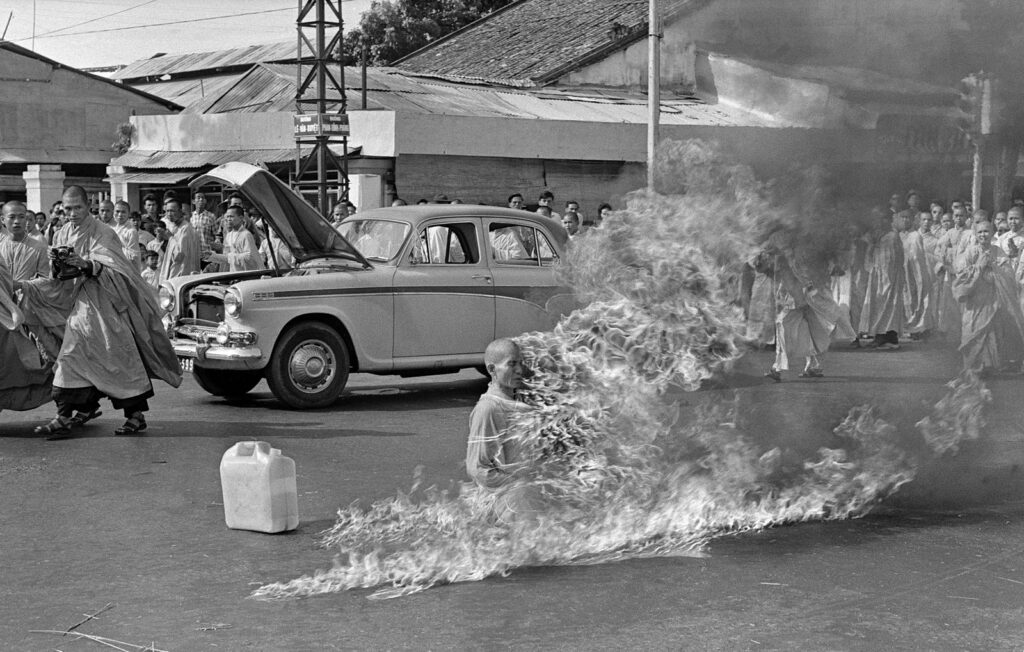

There are few images more moving and more influential than that of Thich Quang Duc and his symbolic self-immolation. In the turbulent landscape of early 1960s South Vietnam, this poignant moment of protest left the world both astonished and captivated.

Thich Quang Duc was a devoted Buddhist monk, living in a nation torn by turmoil and religious strife. He witnessed the clash between the majority Buddhist population and the government and decided to act.

Amidst the tension and unrest, Quang Duc’s act of self-immolation shook the world’s conscience. It raised profound questions about the power of nonviolent resistance and the sacrifices many make in the pursuit of freedom.

Thich Quang Duc – his story and his final act – undoubtedly changed the world forever.

Isolation and Teaching

He was born as Lâm Văn Túc in central Vietnam. He embarked on his path to enlightenment at the age of seven when he left his home to study Buddhism under his uncle.

At 20, he received his monk ordination. From then on, he was known as Thich Quang Duc, a name steeped in Buddhist heritage. Upon emerging from his seclusion, he commenced a transformative journey, traversing central and southern Vietnam to spread the teachings of dharma.

During this period, he played a significant role in constructing 31 different temples, shaping the spiritual landscape of Vietnam. He also spent time in Cambodia to study the Theravada Buddhist tradition.

Over time, Thich Quang Duc’s commitment to Buddhism led him to take on important leadership roles in the community. He served as the Chairman of the Panel on Ceremonial Rites of the Congregation of Vietnamese Monks and as the abbot of the Phuoc Hoa pagoda.

Through his teachings, temple-building endeavors, and spiritual journey, Quang Duc left his mark on Vietnam’s Buddhist community. But his most enduring impact was still yet to come.

Buddhism in South Vietnam

By mid-1963, South Vietnam was mired in unrest. President Ngo Dinh Diem, a member of the Roman Catholic minority, held power in a country where the Buddhist population accounted for the vast majority – between 70 and 90 percent.

Diem’s discriminatory policies favored Catholics in various aspects, from public service and military promotions to land allocation and tax concessions. This bias only exacerbated tensions between the religious communities.

The Catholic Church enjoyed special privileges. They were the largest landowner in the country with exemptions in property acquisition and immunity from land reform. The Vatican flag was frequently displayed at public events. Diem even dedicated the country to the Virgin Mary in 1959.

Meanwhile, Buddhists faced numerous challenges. Months before, Buddhists in Hue protested in the streets waving Buddhist flags for the birthday of Gautama Buddha. Nine people were killed when government forces opened fire on the crowd.

Diem’s refusal to take responsibility for the tragedy and his lack of action toward religious equality fueled more protests and intensified public discontent.

Diem’s autocratic rule persisted. His oppressive policies alienated the population. Public unrest escalated, and Thich Quang Duc decided that further action was necessary.

Against this backdrop of religious discrimination, political repression, and growing dissent, the world would soon bear witness to a moment that would forever change the course of Vietnam’s history.

The Burning Monk

On June 11, 1963, a powerful and deeply symbolic act of protest unfolded on the bustling streets of Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City).

The day before, U.S. press reporters had been told “something important” would be taking place. A handful of members of the press made sure to be present.

That morning, Thich Quang Duc was accompanied by more than 300 Buddhist monks and nuns. They participated in a solemn procession to denounce the discriminatory policies of President Ngo Dinh Diem’s government against Buddhists.

Dressed in his saffron robe, Quang Duc took a seat in the lotus position on a cushion in the middle of the street, in front of onlookers. Two fellow monks poured a five-gallon can of gasoline over him. With extraordinary composure, he struck a match and set himself on fire.

The image of the burning monk is unforgettable. It is both horrifying and awe-inspiring. The flames engulfed his body, yet Thich Quang Duc remained remarkably motionless and silent. He emanated an incredible composure amidst the chaos.

Journalist David Halberstam, who was present, described the haunting scene of Thich Quang Duc’s sacrifice. He remarked, “I was too shocked to cry, too confused to take notes or ask questions, too bewildered even to think.”

The event shocked the world. Photographer Malcolm Browne captured the moment on film for the Associated Press, immortalizing it as an iconic image of the Vietnam War. The photograph of the burning monk won the prestigious World Press Photo of the Year award. It became a potent symbol of the Buddhist struggle for religious freedom and the harsh reality of the situation in Vietnam.

Quang Duc’s self-immolation reverberated across the globe, igniting a wave of empathy and support for the Buddhist cause.

An Intact Heart and a Global Response

In the aftermath of Quang Duc’s self-immolation, the Buddhist community mourned the loss of their revered monk.

The funeral ceremony drew thousands of people. Miraculously, the re-cremation of his body left behind his heart, intact and unburned, which quickly became a symbol of compassion and reverence.

Thich Quang Duc’s protest also sent shockwaves across the world. It garnered international attention and sympathy for the Buddhist monk. The act of sacrifice ignited a wave of protest. It prompted an increase in pressure on President Ngo Dinh Diem to address the crisis.

The powerful image captured by Malcolm Browne even reached President John F. Kennedy, who acknowledged its influence on his perspective towards the South Vietnamese government.

In the end, the incident did mark a turning point. It led to the signing of the Joint Communiqué with concessions made to the Buddhists. The impact of Thich Quang Duc’s sacrifice extended far and wide and inspired further acts of Vietnamese monks self-immolating in the ensuing months.

Ultimately, the mounting discontent and protests played a role in the downfall of Diem’s regime. On November 1, 1963, the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) overthrew Diem in a coup. Diem, along with his brother Nhu, were assassinated the following day.

Thich Quang Duc’s story and his powerful act of protest left a lasting legacy. He inspired generations to come and served as a poignant symbol of the human spirit in the face of oppression.

References

“The Burning Monk, 1963.” Rare Historical Photos, November 25, 2021. https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/the-burning-monk-1963/.

Lindsay, James M. “TWE Remembers: Thich Quang Duc’s Self-Immolation.” Council on Foreign Relations, June 11, 2012. https://www.cfr.org/blog/twe-remembers-thich-quang-ducs-self-immolation.

Worth, Robert F. “How a Single Match Can Ignite a Revolution.” The New York Times, January 21, 2011. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/23/weekinreview/23worth.html.