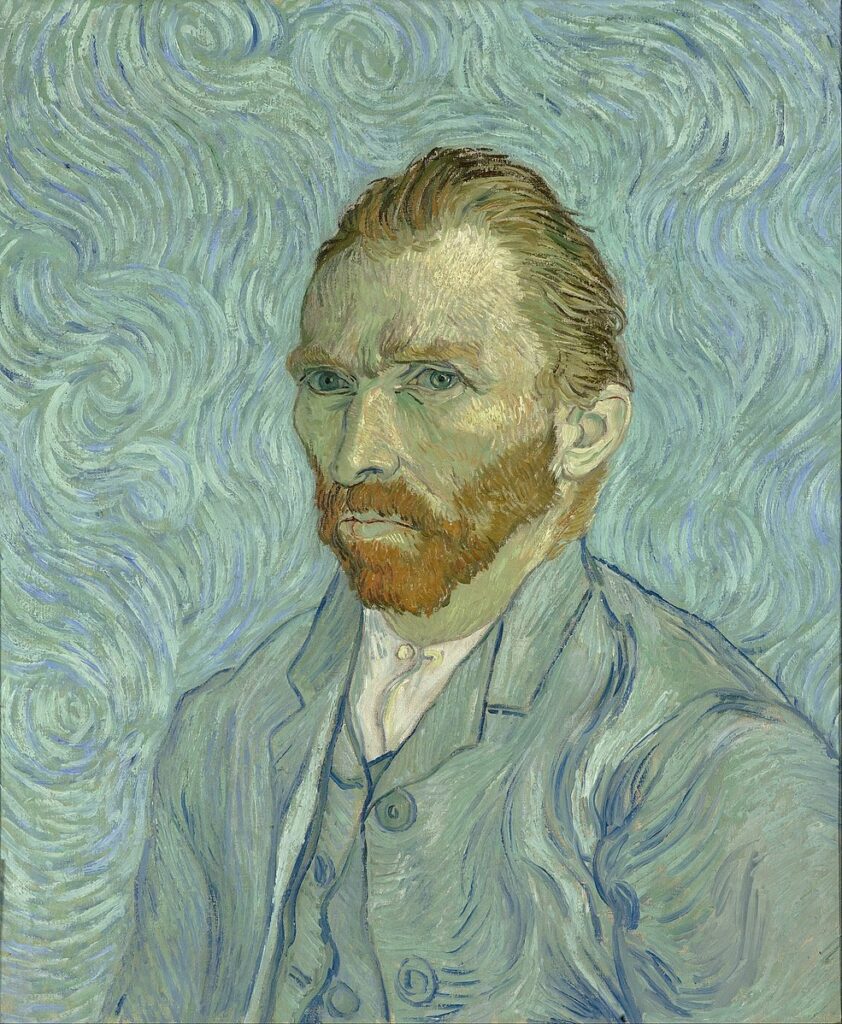

Today, Dutch painter Vincent Van Gogh is considered second only to Rembrandt in raw talent and sheer genius.

His striking use of color, forceful brushwork, and the contoured forms of his work effectively redefined Expressionism in modern art.

In short, he is considered the master painter’s master.

Ironically, Van Gogh sold only one painting in his lifetime. He died at the age of 37 before achieving any real success.

After his death, however, particularly in the late 20th Century, his art became astoundingly popular. His work now sells for astronomical sums of money at auction houses around the world.

“Starry, Starry Night,” for example, one of the most recognizable and “magnificent” pieces of art in the world, is today valued at more than $111 million. Similarly, his “Portrait of Dr. Gachet” is currently the most expensive painting ever sold, valued at over $152 million.

But does Van Gogh owe not only his extraordinary talent (and subsequent recognition as one of the greatest painters to ever live) to a relatively rare condition known as synesthesia? Did Van Gogh see the world differently, and that differentness is what he committed to canvas and we find most alluring?

Who Was Vincent Van Gogh?

Vincent Willem Van Gogh was born on March 30, 1853, in Groot-Zundert, in the province of North Brabant, Netherlands. He was the eldest surviving child of Theodorus van Gogh, a minister of the Dutch Reformed Church, and his wife, Anna Cornelia Carbentus. Van Gogh was named after his grandfather and a brother stillborn exactly one year before his birth.

In May of 1857, his brother Theodorus “Theo” was born.

Van Gogh is said to have been a serious and thoughtful child, even at a very young age. At first, he was schooled at home by his mother and a governess. But at age seven, he was sent to the local village school.

In 1864, at age 11, Van Gogh was placed in a boarding school in the Dutch city of Zevenbergen. But he begged to be brought back home. Instead, in 1866, his parents sent him to the middle school in Tilburg.

It was there that he was introduced to art by Constant Cornelis Huijsmans, a successful Paris artist. Though their relationship would be brief, Huijsmans instilled artistic principles that would materialize in Van Gogh’s work decades later.

At the age of 16, Van Gogh’s uncle Cent secured a position for him at art dealers Goupil & Cie in The Hague. His younger brother “Theo” was already employed there.

After completing his art training in 1873, he was transferred to Goupil’s London branch. This resulted in a short-lived happy time for Van Gogh. He was successful at work and, at just age 20, was earning more money than his father.

However, when his affections were rejected by his landlady’s daughter, Van Gogh became withdrawn and turned to religion. He even considered the ministry.

His father and uncle arranged a transfer from Goupil’s London branch to Paris in 1875. But after a conflict with the local art dealers, he was dismissed after only a year.

The Emerging Artist

To support his growing religious conviction, in 1877 his family sent Van Gogh to live with his uncle Johannes Stricker, who was a respected theologian, in Amsterdam. Van Gogh prepared for the University of Amsterdam theology entrance examination

But, he failed. He left his uncle’s house soon after.

In 1880, Van Gogh moved to Cuesmes (a small village in the province of Hainaut). There, he found lodging with a miner until October of that year.

Though he’d shown an inclination towards art prior to this time, only now did he express a genuine interest. He suddenly found the people and scenes around him fascinating.

He told his brother, Theo, of his new interest. His brother urged him to apply himself to art. Van Gogh did.

Later that year, Van Gogh traveled to Brussels to follow Theo’s suggestion that he study with Dutch artist Willem Roelofs. Upon meeting, Roelofs suggested that Van Gogh attend the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts to study anatomy and the standard rules of perspective and human form.

Following Roelofs’ advice, for the next several months he explored his creativity through painting at Académie Royale.

In Pursuit of Art

The following year, Van Gogh went to The Hague to try to sell his work and meet with his second cousin, Anton Mauve. This cousin was the successful artist Van Gogh now longed to be.

Mauve invited him to return in a few months. He suggested that he spend those months working in charcoal and pastels; which Van Gogh did.

Upon his return, Mauve took Van Gogh on as a student. He introduced him to watercolor, and in early January of 1882, to oil painting.

Impressed with Van Gogh’s creativity, Mauve lent him money to set up his own studio. But within a month, the two had a serious falling out. Possibly over Van Gogh’s habit of hiring women off the street as models. Mauve disapproved of this practice.

In June of 1882, Van Gogh suffered his first bout of gonorrhea and was forced to spend three weeks in the hospital. Soon after, he borrowed money from his brother, Theo, to purchase oils.

He’d discovered that it was the medium he most preferred. He could spread the paint on with a spatula, scrape off the excess from the canvas, and then work back with a brush. (This was the beginning of the technique he would become known for.)

In need of a regular model, Van Gogh formed a living arrangement with a pregnant alcoholic prostitute named Clasina Maria “Sien” Hoornik. She had a five-year-old daughter. On July 2, 1882, Clasina gave birth to a boy, Willem, and moved out. (Many historians believe Van Gogh had fathered the boy.)

Artistry and Insanity

The previous year, Van Gogh wrote the third of more than 600 letters he would write to his brother throughout his lifetime. He now believed himself a marginally successful artist due to the illusion his brother, Theo, had created.

He explained the work he was doing in lithographs (a method of printing originally based on the homogeneous mixing of oil and water). In the letters, Van Gogh provides the first hints that he sees color differently than other people.

A difference his brother, at this time and place, believed was a form of insanity. Van Gogh wrote:

“Some time ago you rightly said that every colorist has his own characteristic scale of colors. This is also the case with Black and White, it is the same after all — one must be able to go from the highest light to the deepest shadow, and this with only a few simple ingredients.

Van Gogh, in a letter to his brother

“Some artists have a nervous hand at drawing, which gives their technique something of the sound peculiar to a violin, for instance, Lemud, Daumier, Lançon — others, for example, Gavarni and Bodmer, remind one more of piano playing. Do you feel this too? Millet is perhaps a stately organ.”

Van Gogh, in a letter to his brother

Scholars today believe Van Gogh was describing a condition known as “synesthetic impression.” This is a form of synesthesia called, “technique-timbre.” As one researcher described it, for Van Gogh, sound had colors and certain colors like yellow and blue were like fireworks to his senses.

What is Synesthesia?

By definition, synesthesia is a perceptual phenomenon in which stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway leads to involuntary experiences in a second. For example, a particular color brings a particular sound to mind.

People who report a lifelong history of such experiences are known as “synesthetes.” Awareness of synesthetic perception varies from individual to individual.

For example, with one common form of synesthesia known as “grapheme–color” synesthesia, letters or numbers are perceived as inherently colored.

Similarly, in “spatial-sequence,” or “number-form” synesthesia, numbers, months of the year, or days of the week elicit precise locations in space. The year 1980, for example, might be perceived as farther away in distance than 1990.

Or, it may appear as a 3-dimensional map (clockwise or counterclockwise). Synesthetic associations can occur in any combination and virtually any number of senses or cognitive pathways can be involved.

Science recognizes two general overall categories of synesthesia: “projective” synesthesia (seeing colors, forms, or shapes when stimulated. This is the most widely understood version of synesthesia).

There is also “associative” synesthesia (feeling a very strong and involuntary connection between the stimulus and the sense that it triggers).

For example, in chromesthesia (sound-to-color), a “projector” may hear a trumpet and see an orange triangle in space. While an “associator” might hear a trumpet and feel very intensely that it sounds “orange.”

Synesthesia can occur between (nearly) any two senses or perceptual modes. In the case of at least one synesthete, Soviet journalist Solomon Shereshevsky, experienced synesthesia linking all five senses: smell, sound, taste, touch, and sight.

In Modern Study

Julia Simner, a psychologist studying synesthesia at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland, estimates that at least 4% of the world population has synesthesia. And that over 1% of those have “grapheme-color” synesthesia (colored numbers and letters).

Her research further suggests the incidence of synesthesia may be higher in people with autism and left-handedness.

Whether or not there is a genetic component to developing this condition is as yet unknown (although researchers are finding a link with Asperger’s Syndrome). However, there are documented cases of non-synesthetes developing synesthesia. This can specifically occur after head trauma, brain tumors, stroke, and temporal lobe epilepsy.

Evidence in Art

Carol Steen, a noted synesthetic artist from New York City and co-founder of the American Synesthesia Association (ASA), has made a study of what she terms “photisms.” These are found in major works of art.

These are shapes that synesthetes see in response to other senses. She first noticed the appearance of photisms in her own work and decided to investigate their prominence in famous works.

According to Steen, of the many Van Gogh works she examined, two in particular demonstrate the “photisms” phenomenon quite clearly: “Starry, Starry Night” (in which they appear as commas in the sky), and “Wheatfields with Crows.” Steen also believes that his self-portraits seem to have brush strokes mirroring the comma forms as well.

In support of her theory, Steen’s art collaborator Greta Berman recently visited the curators at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. She spoke with them about possible evidence of synesthesia in his work.

They had no foreknowledge of the letters describing the phenomenon to his brother. Steen believes this confirms her theory that art provides visual evidence of synesthesia (at least in Van Gogh’s case).

Other Renown Synesthetes (A Partial List):

- American Composer-Conductor Leonard Bernstein (1918–1990)

- Singer-Songwriter Mary J. Blige (1971–)

- Composer-Pianist Duke Ellington (1899–1974)

- French Pianist Hélène Grimaud (1969–)

- Singer-Songwriter Billy Joel (1949–)

- Composer-Virtuoso Pianist Franz Liszt (1811–1886)

- Actress Marilyn Monroe (1926–1962)

- Russian Novelist Vladimir Nabokov (1899–1977)

- Violinist Itzhak Perlman (1945–)

- Russian Composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844–1908)

- Guitarist Eddie Van Halen (1955–2020)

References

psychologytoday.com, “Vincent Van Gogh Was Likely a Synesthete,” https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/sensorium/201308/vincent-van-gogh-was-likely-synesthete

thoughtco.com., “What Is Synesthesia? Definition and Types,” https://www.thoughtco.com/synesthesia-definition-and-types-4153376

Researchgate.net., “The Illness of Vincent Van Gogh,” https://www.researchgate.net/publication/8345093_The_Illness_of_Vincent_van_Gogh

“Vincent Van Gogh Biography,” https://www.vincentvangogh.org/biography.jsp

Historyplex.com., “Famous People With Synesthesia That Everyone Should Know,” https://historyplex.com/famous-people-with-synesthesia

Exploringyourmind.com., “Vincent Van Gogh and the Power of Synesthesia in Art,” https://exploringyourmind.com/vincent-van-gogh-and-the-power-of-synesthesia-in-art/