Last updated on July 20th, 2024 at 09:54 pm

Pontius Pilate was a Roman prefect whose name has become forever entwined with the crucifixion of Jesus Christ.

Despite being a central figure in a story that has been told for over two millennia, we know little about the man himself and the events that shaped his life after the crucifixion.

Early works by Josephus, Eusebius, and other early Christian historians provide a window into his later life, allowing us to try and answer the question: What happened to Pontius Pilate later in life?

The Early Life of Pontius Pilate

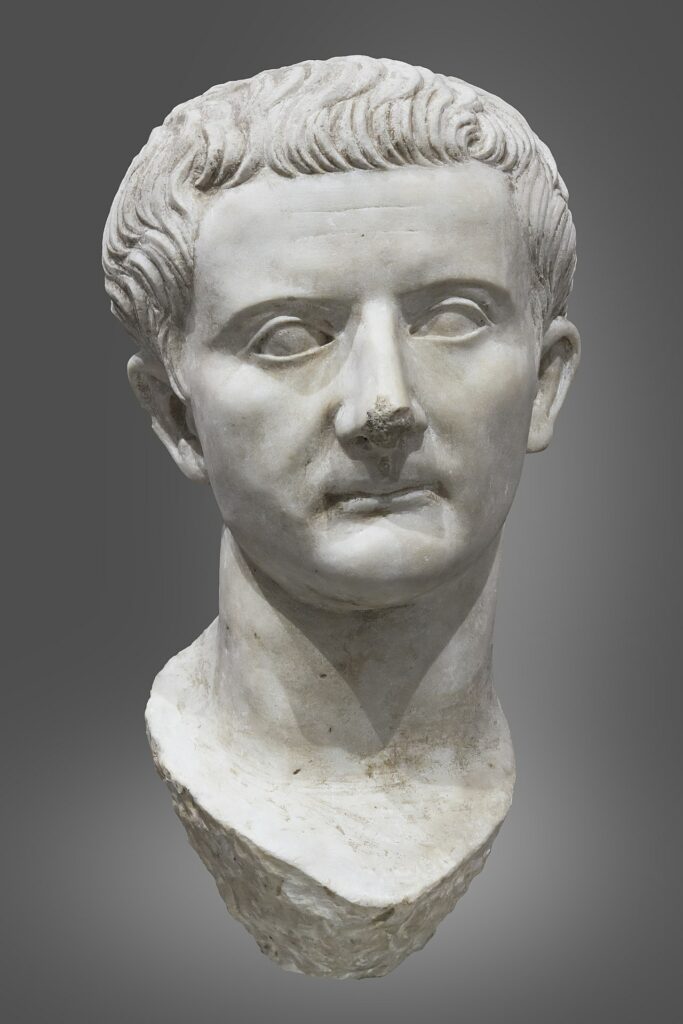

Admittedly, very little is known about the early life of this middling Roman official. But, according to some traditional accounts, he was a knight of the Roman equestrian class and a member of the Samnite clan of the Pontii in Italy.

This explains his name Pontius, but very little else can be verified about his birth, origins, or early life. That is until his appointment to the office that has made him so famous.

In 26 AD, Pilate became the fifth governor of the Roman province of Judaea. He obtained the office through his ties to Sejanus, an extremely influential figure during the reign of the second Roman emperor, Tiberius.

Pilate was to take over in Judaea just twenty years after its last client, king Herod Archelaus, was deposed, and Rome began to rule the region directly.

It was a fractious time as the Jewish people, one of the few subject people of Rome who were monotheists and believed in one rather than multiple gods, were rebellious.

Many groups of Jewish people were also increasingly inclined to follow one of many proclaimed messiahs preaching throughout the province in the first century AD.

The man we know as Jesus was just one of these messiahs operating there during Pilate’s governorship.

Governing Judaea and the Crucifixion of Jesus

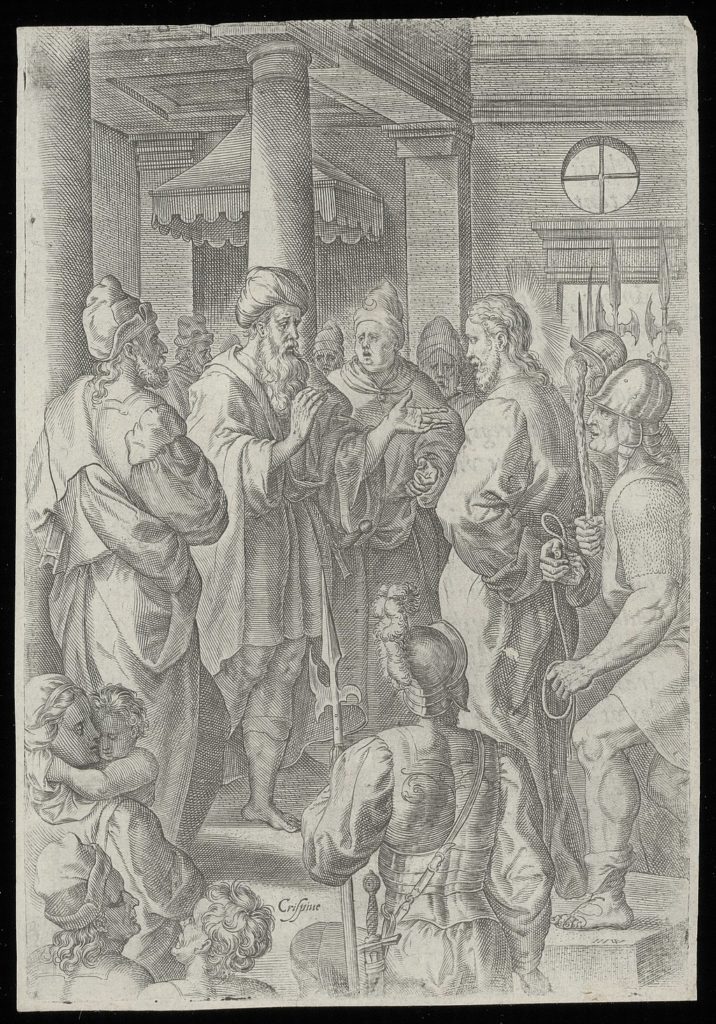

Pilate would govern Roman Judaea for ten years, from 26 AD to 36 AD. It is unclear precisely when Jesus was brought before him and condemned by Jewish leaders.

But some have argued that this occurred in 33 AD. In 31 AD, Sejanus was removed from power and executed weakening Pilate’s position in Judaea now that he had no backer.

Pilate’s decision to appease Jewish leaders and acquiesce to their demands could have come from this weakened position.

This would certainly make sense given that between his appointment in 26 AD and Sejanus’s execution in the autumn of 31 AD, Pilate had generally been deeply antagonistic to the Jewish leaders in the province.

He incited their fury by issuing coins with symbols of the Pagan gods on them and hanging icons of Emperor Tiberius in Jerusalem and other towns across the province, actions which the Jewish people deemed idolatrous.

Given this, it seems likely that Pilate’s more accommodating decision to grant the leaders’ request for Jesus to be crucified occurred when his position as governor of Judaea was weak following Sejanus’s fall from power.

Despite the often apocalyptic depiction of Pilate’s decision to condemn Jesus in the New Testament, this was very likely a typical day as governor. He was simply trying to avoid unrest over Passover if he refused the Jewish leader’s request.

Jesus’ crucifixion did not earn him any ill will from Rome, and he continued successfully ruling the region for years afterward.

What Happened to Pontius Pilate after Jesus?

At some point in 36 AD, a group of Samaritans from Samaria, who were followers of another messiah there, most likely called Dositheos, had begun excavating Mount Gerizim, believing they would find riches and artifacts there associated with the Hebrew prophet Moses.

Pilate ordered some of his legionaries to Mount Gerizim, who preceded to massacre the Samaritans

A complaint was subsequently made to the governor of the neighboring Roman province of Syria, Lucius Vitellius.

He took the complaint seriously enough to send word to Rome, and Pilate was recalled to the Eternal City by Emperor Tiberius to account for his conduct as governor.

When Pilate finally made it to Rome in 37 AD, Tiberius had passed and been succeeded by Emperor Caligula.

It was often the case that individuals in Pilate’s position accused of severe misconduct were pardoned upon the accession of a new emperor.

Because of this, there is a lack of clarity about what happened to Pilate.

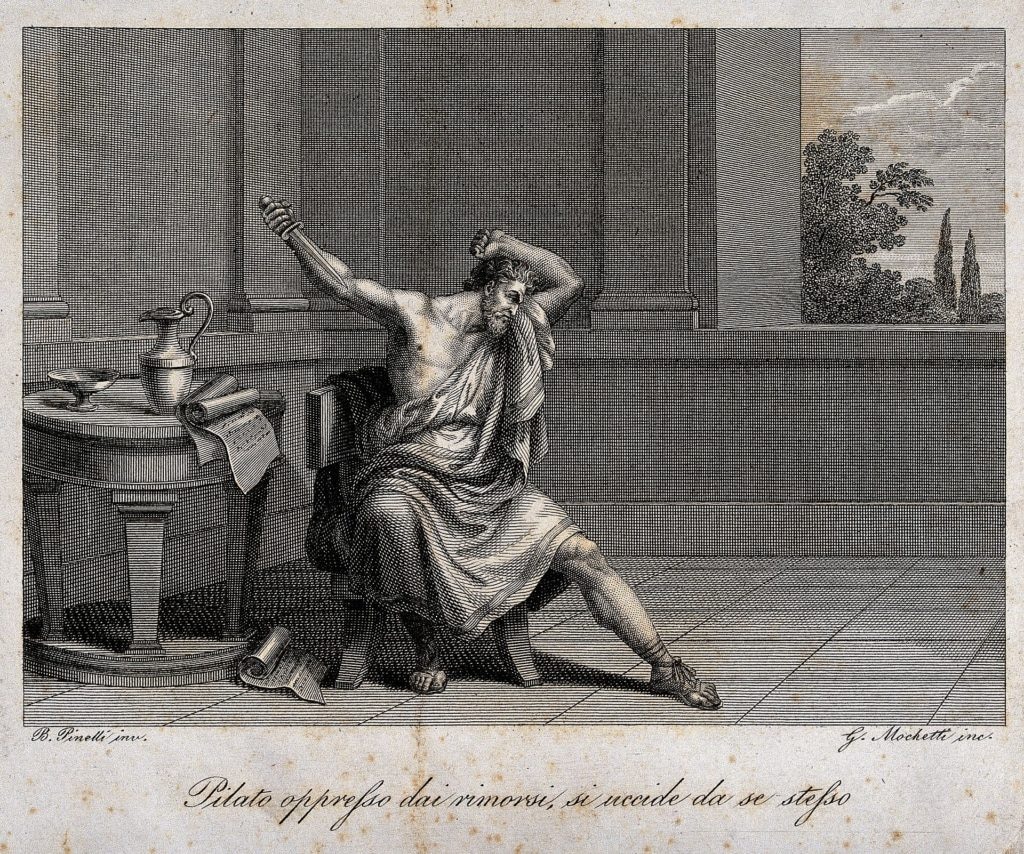

He largely disappears from the historical record, so two competing theories have emerged, for neither of them has sufficient evidence to show what was accurate.

One holds that Pilate fell into disgrace for his actions while governor of Judaea and committed suicide shortly after returning to Rome.

The other contends that Caligula pardoned him, and he retired to a quiet, obscure life on some country estate in the Italian countryside, never to be heard of again until the authors of the New Testament began writing their accounts of Jesus’s life several decades later.

Whichever is the truth of Pontius Pilate’s later years, we know that his reputation is mixed today.

In some Christian traditions, he is seen as a reluctant governor who begrudgingly consented to allow Jesus to be crucified to placate the leaders of the temple of Jerusalem.

The Christian Ethiopian Church and the Coptic Church of Egypt revere Pilate as a Saint.

Others have typically viewed him as an autocratic, violent governor whose role in the slaying of the son of god makes him one of the great villains of Roman history.

The answer to which of these interpretations is most accurate is perhaps as hard to answer as whether he took his own life in 37 AD or lived a long life in retirement after that.

Related Reading

What did Jesus Really Look Like?

Were Modern Depictions of Jesus based on Cesare Borgia?

The Puzzling Search for the Tomb of Jesus

Sources

John F. Hall, ‘The Roman Province of Judea: A Historical Overview’, in Brigham Young University Studies, Vol. 36, No. 3 (1996–7), pp. 319–336.

Paul L. Maier, ‘Sejanus, Pilate, and the Date of the Crucifixion’, in Church History, Vol. 37, No. 1 (1968), pp. 3–13.

Paul L. Maier, ‘The Fate of Pontius Pilate’, in Hermes, Vol. 99 (H. 3) (1971), pp. 362–371.

Tibor Grüll, ‘The Legendary Fate of Pontius Pilate’, in Classica et Mediaevalia, Vol. 61 (2010), pp. 151–176.