Last updated on July 20th, 2024 at 05:56 pm

Politics can be cruel sometimes, that’s for sure. In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crash, for instance, many prime ministers and presidents were quickly removed from power in countries across North America and Europe by electorates furious at what had happened.

Some of these same leaders had only just entered office before the crash and weren’t responsible for the crisis. But they were given their marching orders.

Yet perhaps they should have accounted themselves lucky to be out of a job. In earlier times, people in their position faced far worse consequences when things went awry.

Look at the example of Johan de Witt, the head of the Dutch Republic in the mid-seventeenth century, who, after a series of negative events in the early 1670s, was murdered in The Hague on the 20th of August 1672. And then his killers at least partially ate his body and that of his brother Cornelis.

The Dutch Republic

Let’s backtrack a little to try to understand what drove the Dutch people to acts of cannibalism.

The Dutch Republic was a new power in the seventeenth century. During the sixteenth century, the Low Countries were ruled by the House of Habsburg, the monarchs of which Charles V and then his son Philip II, were also Kings of Spain.

But owing to unrest within the Dutch provinces of Holland and Zeeland in the 1560s at high taxes and religious oppression, the Dutch nobility and towns revolted against Spanish rule.

hey were led in particular by the leaders of the House of Orange, the most powerful of the Dutch aristocrats, who also held lands in France.

Beginning in 1568, the Dutch waged a war of independence against Spain, which lasted for eighty years on and off before the Spanish finally accepted defeat and acknowledged the Dutch Republic as an independent state in 1648.

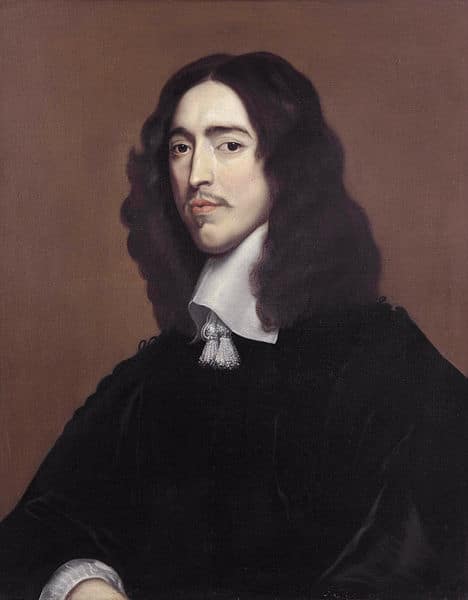

Johan and Cornelis de Witt

Now the newly independent Dutch Republic was a powerful entity. As economic power in Europe switched from the Mediterranean to the North Atlantic in the seventeenth century, Amsterdam became a major financial and mercantile powerhouse.

As such, there was a Golden Age of Dutch culture at this time. But the fledgling republic remained dominated by the House of Orange.

That is until the mid-seventeenth century when Johan de Witt and his brother, Cornelis de Witt, led a faction of lesser Dutch nobles and merchants who wanted to adopt a more republican model.

Beginning in 1650, they largely succeeded in doing so. For the next twenty-plus years in the republic, power passed to more minor nobles, such as the de Witts and the merchant companies of the major towns in an increasingly decentralized republic.

Johan de Witt served as the equivalent of the country’s Prime Minister from 1653 onwards, though the actual title he held was the Grand Pensionary.

All went well for many years. The Dutch Republic continued to punch way above its weight in terms of its European and colonial trade dominance, bringing enormous wealth into cities such as Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and Dordrecht. But it wasn’t to last forever.

European Hostilities towards the Dutch Republic

The other European powers were increasingly hostile towards the Dutch Republic and its dominance of Atlantic trade.

This was an age where the primary economic philosophy was mercantilism, which argued that a finite amount of trade would be carried out globally. Each nation could only increase its share by acquiring the trade of other nations.

Consequently, between the 1650s and the 1670s, several larger European nations went to war with the Dutch every few years to crush their economic might. In particular, the Dutch were threatened on the high seas by England and on land by France.

This period of intense aggression culminated in 1672 in the outbreak of two separate wars in just 24 hours. On the 6th of April, France declared war on the Dutch Republic, and the following day the British did the same.

These are treated as two separate conflicts as the French and British had separate goals and would make peace with the Dutch years later on separate terms.

Thus, one is viewed as the Franco-Dutch War and the other as the Third Anglo-Dutch War.

The combination of French and British aggression was initially disastrous for de Witt’s government. In June, the French, allied with several small German states of the Rhineland, invaded the Netherlands from the east and inflicted a series of stunning military defeats on the Dutch.

The town of Groenlo was seized by the French within days, and most of the south of the Republic was overrun. Panic set in in Amsterdam and The Hague as it was feared that the French would capture the cities. All of this made the period known as the Rampjaar or ‘Disaster Year.’

Murdering and Cannibalizing the de Witts

This was the context in which the de Witts were murdered by their people. Early in August, Cornelis de Witt was arrested and imprisoned in The Hague.

On the 20th of August, his brother Johan visited him in jail. But little did he know that his political enemies, in conspiracy with the head of the House of Orange, William of Orange, had laid a trap for him.

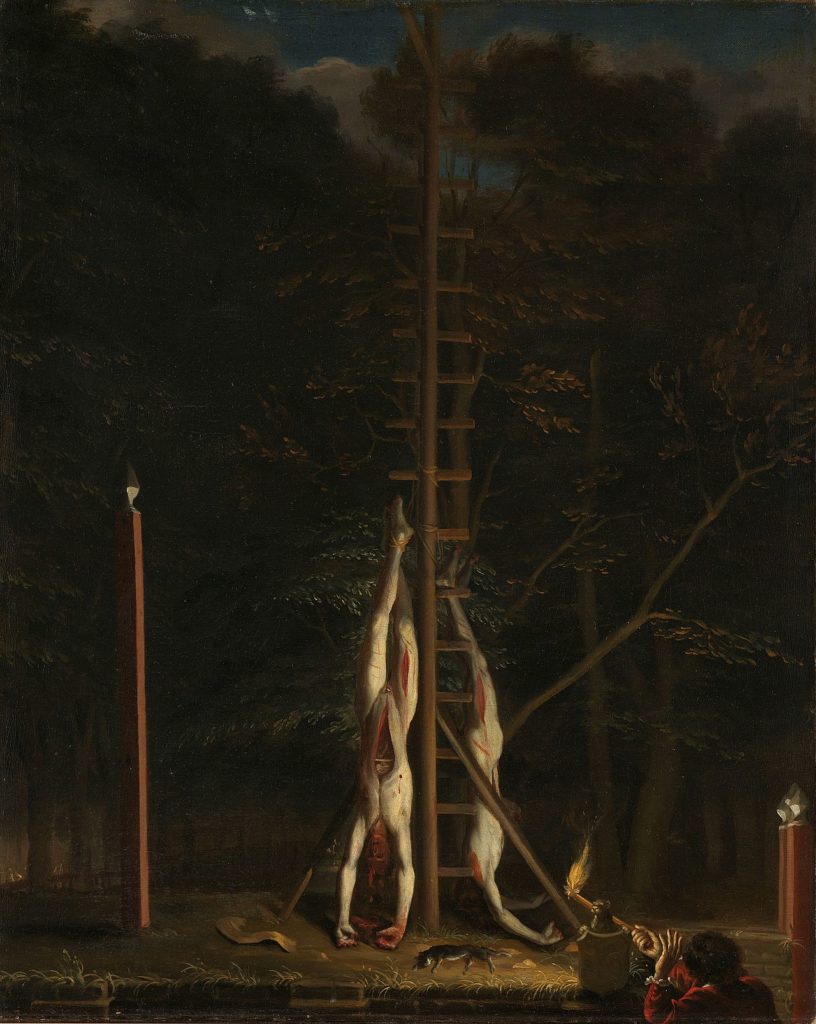

After de Witt entered, a crowd gathered around the prison, and The Hague militia moved in. But rather than quelling the unrest, they stormed the prison and killed the two brothers.

Afterward, their bodies were strung up on a gibbet and mutilated, and the crowd engaged in acts of cannibalism of their desecrated corpses.

A particularly gory element of this was their roasting and consumption of their livers. Observers noted how orderly these events were, and this was a symbolic act of extremely orchestrated violence by the Orangists to make clear their reassertion of power in the Republic.

The bizarre thing is that the war effort had improved for the Dutch by the early autumn, and the Dutch managed to expel the French from the Republic soon afterward.

Thus, the de Witts’ fate was especially cruel. In the aftermath of the infamous murder and episode of cannibalism, a pro-Orange politician called Gaspar Fagel succeeded Johan de Witt as Grand Pensionary.

The war with the English ended in 1674 mainly in a draw, while the war with France constituted a similar return to the status quo ante bellum, ‘the state in which things were before the war.’

And what happened to William of Orange? After the alleged acts of cannibalism, he became the preponderant figure within the Dutch Republic, reasserting the power of the House of Orange that the de Witts had challenged.

Then, owing to his marriage to Mary Stuart, the daughter of James, Duke of York, in 1677, he acquired a claim to the English throne, one which he successfully imposed in 1689, usurping the crown from his father-in-law.

Thus, the murder of the de Witts paved the way for William to become one of the most successful statesmen of late seventeenth-century Europe.

Read More

If you enjoyed this article, here are some more you might like:

Gibbeting: A History of a Gruesome Form of Public Execution

Did Cannibals really eat Michael Rockefeller?

Sources

Jonathan Israel, The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness and Fall, 1477–1806 (Oxford, 1995).

Herbert H. Rowen, John de Witt: Statesman of the “True Freedom” (Cambridge, 1986).

D. R. Hainsworth and C. Churches, The Anglo-Dutch Naval Wars, 1652–1674 (London, 1998).

Annette Munt, ‘The Impact of the Rampjaar on Dutch Golden Age Culture’, in Dutch Crossing, Vol. 21, No. 1 (1997), pp. 3–51.

Tony Claydon, William III: Profiles in Power (London, 2002).