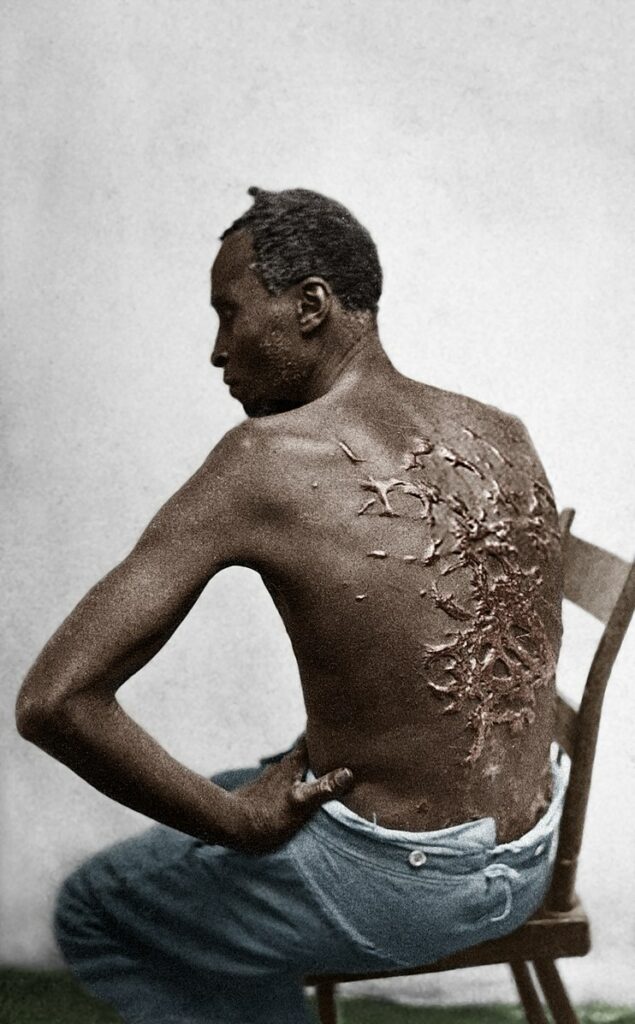

The history of American slavery is a dark, difficult period in the nation’s past. However, there exists a figure whose experience transcends mere words – a visceral and deeply evocative visual testimony to the cruelty endured by enslaved individuals.

Whipped Peter is an anonymous figure whose suffering and resilience have been etched into history through his scars. His story is evidence of the cruelty of slavery. Whipped Peter’s story is one of anguish and endurance, captured through the haunting photographs that carry his story and remember his legacy.

But who was he? What story lurks behind the compelling photos that made him such an infamous figure? The history of Whipped Peter, a figure whose scars speak louder than words, beckons us to confront the truths hidden within the shadows of our collective history.

The Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation came into effect on the first day of the year 1863. It freed the slaves of the Confederate territories. It wouldn’t be until January 29 that the proclamation was finally applied in Louisiana. Still, despite the proclamation, the U.S. Army initially refrained from intervening to help free those enslaved.

Nonetheless, as the Civil War raged on, thousands of formerly enslaved people sought refuge with the Union Army. While officers and soldiers were instructed not to encourage or force the slaves to leave their employers, many followed Union troops, forming columns of freed individuals.

Refugee camps, known as contraband camps, were established alongside Union military fortifications. They provided shelter and support to those seeking freedom.

Eventually, many contrabands were recruited into the ranks of the U.S. Colored Troops (USCT). These comprised around 10 percent of the Union Army’s manpower by the end of the war.

The Emancipation Proclamation marked a pivotal moment in the struggle for freedom in the US, and its impact on the lives of enslaved individuals was profound. Especially to a man named Peter.

Runaway

In a daring bid for freedom on March 24, 1863, an enslaved man named Peter embarked on a treacherous journey toward liberty.

Peter fled his 3,000-acre Louisiana plantation. He made his way eastward, seeking refuge along the Mississippi River. His master and neighbors used bloodhounds to track him down, but Peter’s ingenuity saved him.

He carried onions from the plantation with him. He rubbed them on his body to throw off the scent, successfully evading capture. After an arduous ten-day journey, he finally found sanctuary with Union soldiers in Baton Rouge.

At the encampment, Peter decided to seize the opportunity President Lincoln had recently granted African Americans: to enlist in the Union Army.

With this decision, he became one of the pioneers in a movement that would see nearly 200,000 African Americans join segregated units. However, it was during his medical examination for enlistment that military doctors discovered shocking, extensive scars covering his entire back.

At that moment, photographer William D. McPherson and his assistant, Oliver, were present in the camp. They captured the powerful image of Peter, known thereafter as Whipped Peter.

Whipped Peter’s Account

A letter attributed to “the Bostonian” dated November 12, 1863, gives the account of “Poor Peter.” The letter was in response to skepticism regarding the now-famous photograph depicting Peter’s lacerated back.

According to the letter, Peter, who could speak little English and mainly communicated in French, shared a heart-wrenching story of his escape from a plantation where he was owned by Captain John Lyon, a cotton planter.

When questioned about the reason for his escape, he alluded to the cruelty of his owner, suggesting that he was whipped by his Overseer, Artayon Carrier. He recounted how he was subjected to salt brine, which left him bedridden for two months.

Peter’s memory was clouded by the trauma, and he had little recollection of his actions during that time. He recounted that he had been labeled as “sort of crazy” after the incident, and that in a moment of despair and desperation, he had burned all his clothes but had no recollection of doing so.

Nevertheless, his brave escape and the visual evidence of his scars painted a powerful picture of the abuses suffered by enslaved individuals.

The account of “Poor Peter” stands as a chilling testament to the physical and psychological suffering endured by enslaved individuals during the era of American slavery. And thanks to the photo taken by McPherson and Oliver, many more would bear witness to his story.

The Power of a Photo

The iconic photograph of Whipped Peter emerged as one of the most powerful and widely circulated images of the abolitionist movement during the American Civil War.

Published in Harper’s Weekly on July 4, 1863, this photograph depicted the scourged back of an individual they named “Gordon.” It provided Northerners with compelling visual evidence of the brutal treatment endured by enslaved individuals.

Alongside two other photos, the article was titled “A Typical Negro.” It aimed to illustrate the suffering and resilience of enslaved people in the United States. It also told the story of Gordon’s escape.

This added a remarkable layer to his quest for freedom. According to Harper’s account, he successfully evaded the bloodhounds chasing him by carrying onions from his plantation in his pockets. After crossing creeks and swamps, he rubbed his body with the onions to mask his scent, ultimately finding refuge with Union soldiers stationed in Baton Rouge.

Sound familiar? Historians have long debated the accuracy of the narrative accompanying the images, which presented a generalized legend rather than an entirely factual account of Gordon’s life and escape.

The historical figure of Gordon and the person known as Whipped Peter are believed to be two separate individuals, likely combined by Harper’s for narrative convenience. But the photograph matches those taken of Peter. It’s believed they may have been two individuals in a group traveling together in their flight to freedom.

Regardless of this discrepancy, the photograph served as a catalyst for inspiring many free blacks to enlist in the Union Army. They were determined to fight for their own freedom and the liberation of others still in bondage.

The image of Whipped Peter and his scarred back, along with the narrative of his escape, left a profound impact on the American public. It demonstrated how photography as a medium could shape history and galvanize support for the abolitionist cause.

Even today, many find inspiration and incredible power in the picture. Certainly, the image of Whipped Peter will be remembered as one of the most influential photographs in American history.

References

Silkenat, David. “‘A Typical Negro’: Gordon, Peter, Vincent Colyer, and the Story behind Slavery’s Most Famous Photograph.” American Nineteenth Century History 15, no. 2 (2014): 169–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664658.2014.939807.

“A Slave Named Gordon.” The New York Times, October 1, 2009. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/04/books/review/Letters-t-ASLAVENAMEDG_LETTERS.html

“The Whipping Scars on the Back of the Fugitive Slave Named Gordon.” US Slave Blog, October 13, 2011. http://usslave.blogspot.com/2011/10/whipping-scars-on-back-of-fugitive.html.“

[Escaped Slave Gordon, Also Known as ‘Whipped Peter,’ Showing His Scarred Back at a Medical Examination, Baton Rouge, Louisiana].” The Library of Congress. Accessed July 20, 2023. https://www.loc.gov/item/2018648117/.