Many people are familiar only with the bare facts about the Civil War. The average person that you ask about this topic on the street will tell you that the war was between the North and the South and that the North won. They might also be able to tell you that Abraham Lincoln was around, and it somehow involved that slavery.

On the face of it, these are some of the story’s highlights. However, the Civil War was a deeply complex conflict that had lasting impacts on American society well beyond the years when soldiers who might be brothers, cousins, or friends fought with one another in farmer’s fields.

Moreover, the Reconstruction era, which followed the end of the Civil War, would forever change the fabric of the United States and create lasting grudges still being felt in politics and the social landscape today.

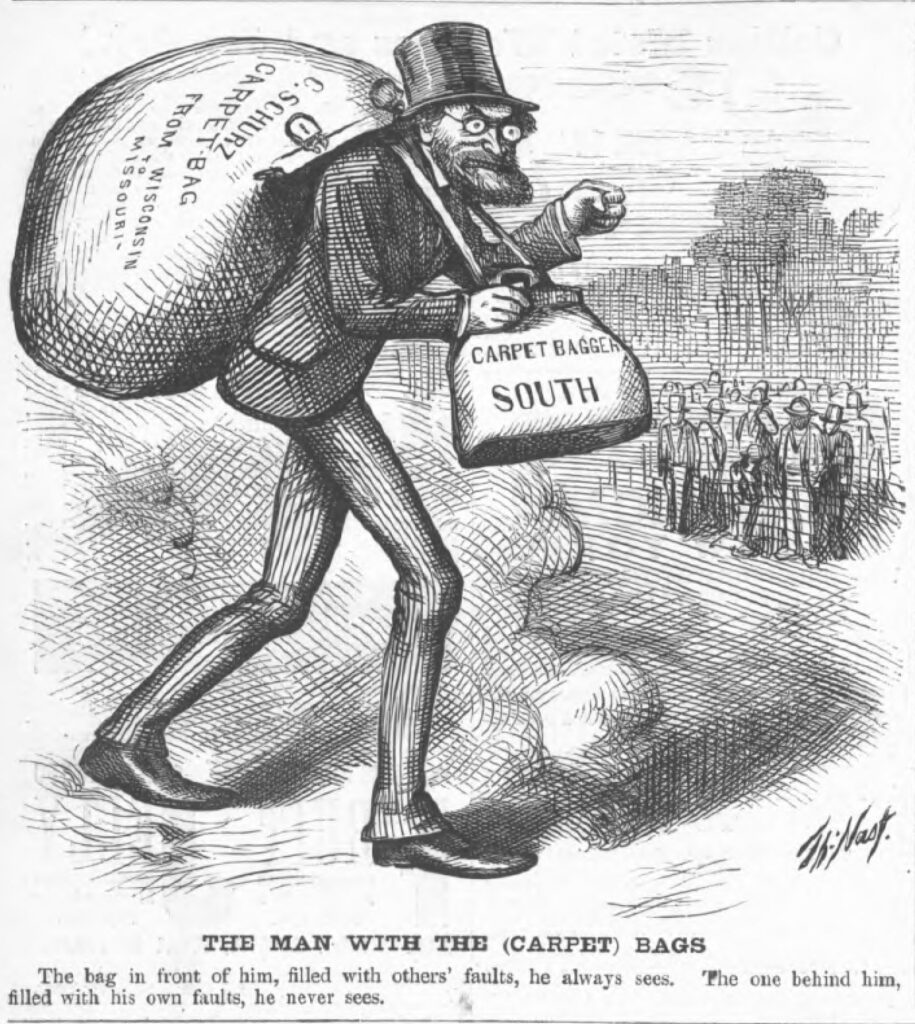

Who Were The Carpetbaggers?

Carpetbaggers was a term used to refer to anyone, not from the South who relocated from the North following the war’s end. This action was viewed as opportunism by the Southerners who had lost their way of life, and resentment against carpetbaggers was deep and entrenched.

In Gone With the Wind, Scarlett notes bitterly, “She remembered all too vividly her struggles during those first days of Reconstruction, her fears that the soldiers and the Carpetbaggers would confiscate her money and her property” (Mitchell, 1936).

This sentiment was common to nearly all Southerners at this time. The South was stunned that they had lost the war, shocked that their slaves had been told they were free and horrified that no economy was left to support their way of life.

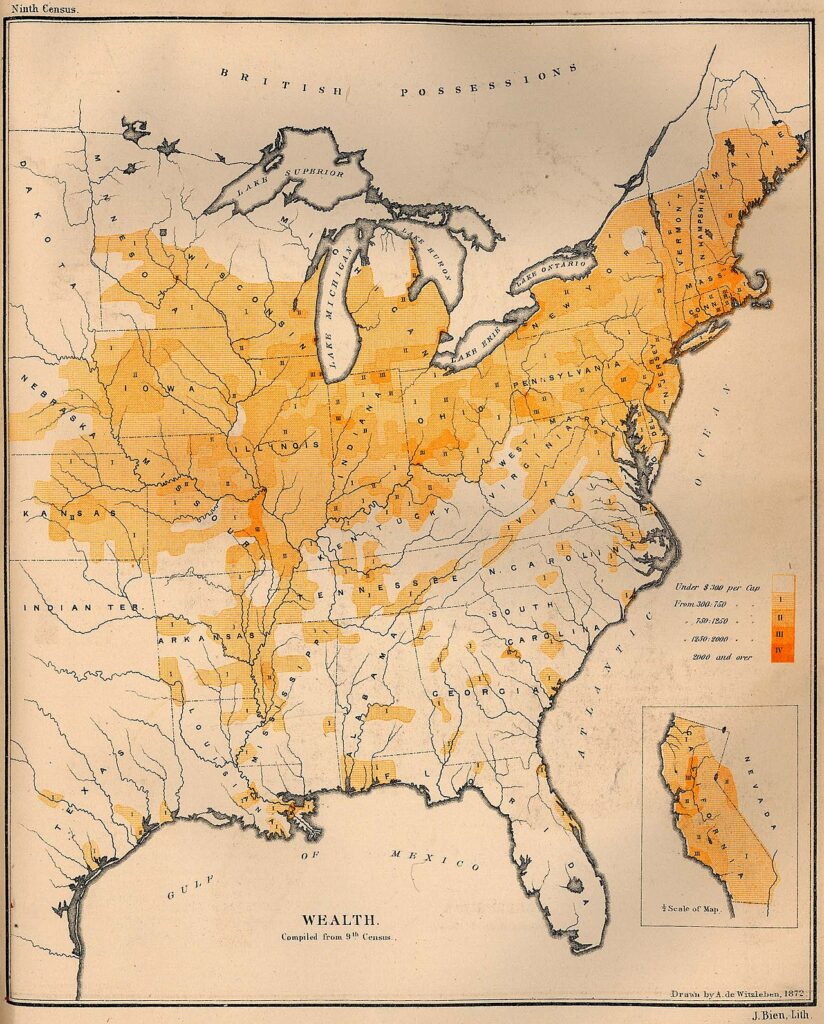

The South had made a critical error when they had determined that they would attempt to split from the North. They had forgotten how little industry they had access to at home. An agrarian society that was only able to make money through the use of Slave labor was not viable in the Reconstruction reality.

The reality is that people did come to the South from the North following the end of the Civil War, and while many of them did lease plantations or buy property for paltry sums of money, they, too, struggled to build something for themselves from the ruins.

There was no bounty left to collect from the war-torn and scarred landscape of the South, and even the Carpetbaggers would find that Reconstruction was not going to be as rapid as they had been promised.

The Carpetbaggers were usually well-educated members of the middle class. They might be teachers or merchants, and many were former Union soldiers.

Many of them were motivated by a sense of opportunity or a desire to help the South recover from the war. Louis F. Post recounted his travels to the South after the Civil War in A Carpetbagger in South Carolina, stating, “I did not go to South Carolina as a ‘carpetbagger.’ I did not intend to be one. My expectations were to become a South Carolinan.” (Post, 1925)

His story was a common one, and the bitterness and brokenness of the South shocked him and sent him back home to New York after just one year.

Who Were the Scalawags?

Perhaps more hated than the Carpetbaggers were the Scalawags, native Southerners who wanted to recognize the civil rights of former slaves and were willing to join the radical Reconstruction-era legislature.

The social conflict that lay at the heart of the hatred of the Scalawags was founded in the class system that the South had held close to its breast before the war.

Middle-class and lower-class whites in the South before the war were made to feel inferior and were often held in some contempt. Now, these people were offered the chance to make a name for themselves and influence how the South recreated itself in the aftermath of the war.

Since many of the Scalawags of note called the northern states of the region home, the deep South viewed them as interlopers who had never been asked to the table in the first place.

Scalawags were popularized by the Reconstruction-era newspapers and named public enemy number one. This led to the lumping of many different kinds of people referred to by this negative term.

In reality, Scalawags were secessionists from the Union but also from the former slave-holding states. They were also former slave owners, yeoman farmers, and even former Whigs. Notable people also fleshed out their ranks, and Robert E. Lee’s second in command, James Longstreet, was considered a Scalawag. (Britannica, 2019)

Scalawags, at this time, made up about twenty percent of the white electorate (History.com, 2018), and they were quite influential. Never had it been so clear to the former ruling class of the South that their way of life had been built upon flimsy pillars that meant nothing in the post-war reality.

The Republican Party was supported in great numbers by white Southerners, but this is not mentioned in the folklore that is commonly associated with the Reconstruction era.

Contemporaries who lived through the years following the Civil War would likely have hated Scalawags far more than Carpetbaggers. After all, these were people who Democrats had expected to be able to count upon after the war.

The critical role that Scalawags played in the transition that took place after the war is often overlooked and overshadowed by angst about Carpetbaggers. However, Carpetbaggers rarely stayed for the long haul, and Scalawags were already established Southerners who were not going anywhere.

While it is not known who first coined the use of the word Scalawag to denote someone who was a traitor to their race in the South, Scalawags were the largest force for social change during this period and likely also the most reviled of the interlopers who worked hard to change post-war Southern society for good.

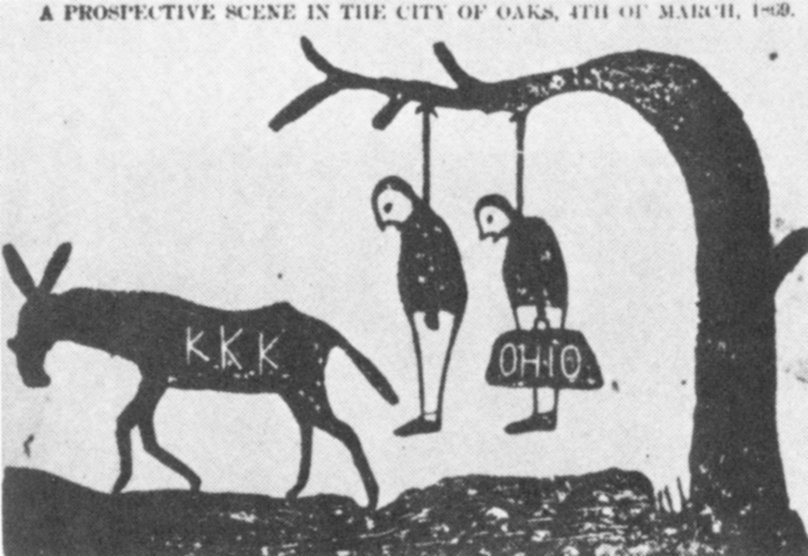

Carpetbaggers and the Ku Klux Klan

One of the more sinister aspects of the post-war reality in the South was the ongoing struggle over the rights of African Americans. The deep South, in particular, was deeply angered by the freeing of the slaves. Without slave labor, the agrarian riches which had sustained them were no longer possible.

Out of the chaos of the Reconstruction era came the Ku Klux Klan. In some areas, they were little more than rowdy groups of miscreants having a bit of fun in a time when law and order were quite limited. In other places, however, the Klan considered itself a league of men concerned with justice and safety.

To the minds of ardent Klansmen, former slaves threatened the safety of their wives and children, and they needed to be removed forcibly from areas where whites were living.

Slavery might have been legally abolished, and equal protection under the law might have been promised to the former slave populations of Southern states. Still, the reality was that there was no large presence of supporters to back up these promises in the South.

White supremacists, both natives and those who had relocated to the South after the war, were swift in their retribution. By 1877, lynchings and terror against black citizens increased (Jones, 2020).

The terrors and indecencies that were caused by members of the Klan in the Reconstruction-era South were done in the name of a false sense of chivalry (Martinez, 2007). These terrible and criminal actions have had lingering impacts on the social fabric of the South, and the fact that the Klan continues to exist speaks clearly about the lasting impact that Reconstruction has had on the Southern states.

Homegrown terror in the hands of the KKK has been at the heart of many racial issues in the South for generations and it continues to be a factor in the politics of the states which gave the Klan life.

The Myth of the Carpetbagger

One of the lasting legacies of the Carpetbagger has been the link between these very real people who moved to the South after the Civil War and the politics of the time. Carpetbaggers were blamed, perhaps erroneously, for the way that the South was guided toward a more radical, democratic political future.

Today, Carpetbagger is a derogatory term that is bandied about in politics all the time. The word is used to indicate that someone has trespassed and left the place they belong in search of opportunities at the expense of others.

In politics, this is connected with a sense of throwing one’s weight toward the winning team, even if this means going against the beliefs and principles that you have stated to hold in the past.

Carpetbagger was a derogatory term well before the Civil War, but its use to indicate that someone is a traitor to the things that “everyone else” upholds to be true is a lasting repercussion of the Civil War era.

It is politically expedient, in many cases, to indicate that someone who is trying to change sides is a “carpetbagger” who is just jumping into bed with new friends for expediency. The current use of the word with this association is directly linked with Reconstruction-era politics and the negative connotations that the word bore at this time.

It is no surprise that the word Carpetbagger is used more frequently when discussing political issues in the South as compared to political events in other parts of the United States. This is because the deep South continues to identify with issues that reared their heads during the Reconstruction era, and these kinds of terms have remained relevant in Southern politics for generations.

The Legacy of Reconstruction

Reconstruction has always been a difficult concept to grapple with and discuss. This is partially because of the efforts of contemporary journalists and authors to promote an agenda that implied that the Reconstruction era and the Civil War itself had unjustly snuffed out the beautiful and graceful Southern way of life.

The focus on what has supposedly been lost overlooks the abuse of other humans through slavery, an economy that was built on the backs of people who were treated like little more than possessions, and an entire way of life that was becoming obsolete before the war came to tear it from its moorings.

Reconstruction was a time of great upheaval, and for those who lived it, Carpetbaggers and Scalawags were not the only frightening specters looming over them.

Starvation, the lack of an economy, and the staggering number of lives that had been lost during the war likely loomed larger in the minds of Southerners. Rape, theft, and aggression were commonplace as women living alone became prey to roving bands of deserting soldiers and opportunists.

Reconstruction is often viewed through the lens of politics or is reviewed with an eye to the issues of property ownership or migration. The reality is that Reconstruction was a much lengthier process than it was intended to be, and it was a time of great social turmoil, political upheaval, and loss for Americans as a whole.

No matter what kind of good intentions some of the Carpetbaggers or Scalawags might have had in mind, the reality was that the South, as everyone had known it, had died, and an entirely new entity was being born from its ashes.

The Carpetbaggers and Scalawags of the Reconstruction era helped create a new future for the South, but they did not do so without causing their own bloodshed, chaos, and suffering.

The South did not rise like a phoenix from the ashes after the end of the Civil War, and the difficulty of the Reconstruction period continues to be felt, even today.

Sources

Mitchell, Margaret. Gone With the Wind. Scribner, 1936.

Post, Louis F. A Carpetbagger in South Carolina. 1925, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.2307/2713666, 1925.

History.com. Carpetbaggers and Scalawags. 2018, https://www.history.com/topics/american-civil-war/carpetbaggers-and-scalawags, 2018.

Martinez, J. Michael. Carpetbaggers and Scalawags. Rowan & Littlefield, 2007.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “scalawag”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 23 Aug. 2019, https://www.britannica.com/topic/scalawag-United-States-history. Accessed 5 January 2023.

Jones, Thai. Reflecting on the History and Legacies of Reconstruction. Columbia News, 2020, https://news.columbia.edu/news/why-reconstruction-matters-panel-with-crenshaw-foner-gates#:~:text=Occurring%20during%20the%20decade%20following,vote%20and%20hold%20political%20office.