At the start of the 20th Century, Europe’s political scenario was in a state of upheaval. Emerging nationalist movements in several parts of Europe were threatening the established order.

By 1914, when a Serbian nationalist assassinated the Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the stage was already set for a major conflict that would draw in the world’s greatest powers. World War I raged from 1914 to 1918, and it revolutionized the act of warfare itself.

The two sides fighting in WWI were the Central Powers, consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire, and the Allies, which included Britain, France, Russia, and the U.S. Other countries were also drawn into the conflict on both sides, such as Bulgaria for the Central Powers and Serbia and Japan for the Allies. Both sides suffered heavy losses, and WWI concluded with an estimated 16 million dead.

WWI Generals: An Undeserved Reputation?

Historians have called WWI a “meat grinder” because of the shockingly high death toll during the conflict. At the time, people referred to WWI as “The Great War” or “The War to End All Wars” since there had never been a global conflict of such a scale. While WWI did not actually end all future wars, it forever changed the way warfare was conducted.

It was WWI that saw the arrival of war machines like tanks and aircraft on the battlefield for the first time. Also, advancements in military technology, such as the development of machine guns, rewrote the rules of infantry engagements. Mobile operations were no longer as effective against modern defense systems, necessitating longer and harsher battles fought in trenches.

Because of the high human cost of WWI, the generals of both sides have been characterized as callous and anachronistic in their approach. Some generals made the mistake of sticking with tactics like frontal assaults and cavalry charges, even when those methods were woefully outdated, thanks to advancements in military technology.

The description of WWI’s fighting forces as “lions led by donkeys” has been repeated frequently. This description depicts the generals of WWI as incompetent and stubborn, while the soldiers were capable men led by incapable leaders.

While there is definitely some merit to these arguments, it’s also important to mention that the WWI generals faced an extremely challenging task. As military strategists, they had to adapt to new technologies and tactics while seeking to exploit any advantage they found.

At the time WWI broke out, nobody could have predicted the upheaval it would cause. Knowing now that the WWI generals were men in an era-defining conflict doing their very best, it is possible to revisit their legacy with a less critical perspective.

Four Chief Allied Commanders of WWI

The Allied commanders of WWI hailed mainly from the countries in the Triple Entente: England, France, and Russia.

Generals from other countries, such as Belgium and Italy also, made valuable contributions to the Allies’ war effort in their localized theaters.

Lt. General Baron Jacques of Belgium and General Armando Vittorio Diaz of Italy were gifted leaders in their own right, and their actions against the Central Powers’ forces helped turn the tide of WWI in favor of the Allies.

Still, it was the armies of the Triple Entente powers that spent the most time fighting in the field against the Central Powers.

Over the course of four brutal years, these commanders had to shoulder the responsibility of leading men into a war that had snowballed into a much greater conflict than first expected. Here are the top Allied commanders of WWI and their accomplishments during the war.

1. Joseph Joffre

When discussing the mixed legacy of WWI generals, the French general Joseph Jacques Cesaire Joffre is a prime example.

On the one hand, he enjoyed tremendous popular support, with the masses referring to him as “Papa Joffre.” On the other hand, Joffre was also unable to make any decisive gains against the Central Powers, which ultimately led to his dismissal as commander-in-chief.

What was the cause for Joffre’s contradictory legacy?

His detractors point to his formulation of Plan XVII, the French strategy of WWI, which had demonstrably poor results in the field. When WWI began, Joffre advocated pursuing frontal attacks across German lines, a tactic that was ineffective against entrenched German positions fortified with modern artillery and machine guns.

Though Joffre supported an offensive strategy, the reality was that he proved his worth when placed on the defensive. After his plan of frontal assaults against advancing German forces proved futile, Joffre was able to react wisely to the situation and pull back to Paris in time for the First Battle of the Marne.

By virtue of leading the defense of the French capital, Joffre earned the title “The Victor of the Marne,” and this remains his greatest achievement. After months of diminishing results, including being caught unawares by German forces at the Battle of Verdun, Joffre finally stepped down from his command position in 1916.

Despite his checkered success rate, Joffre was vital for the Allies’ fortunes, especially in the first half of WWI. By thwarting the Germans at the First Battle of the Marne in 1914, Joffre was able to derail the German plan of swiftly ending hostilities on the Western Front.

This bought the Allies valuable time where they could make advances in other theaters, such as Turkey and Italy, while holding back the Central Powers in Northern and Western Europe.

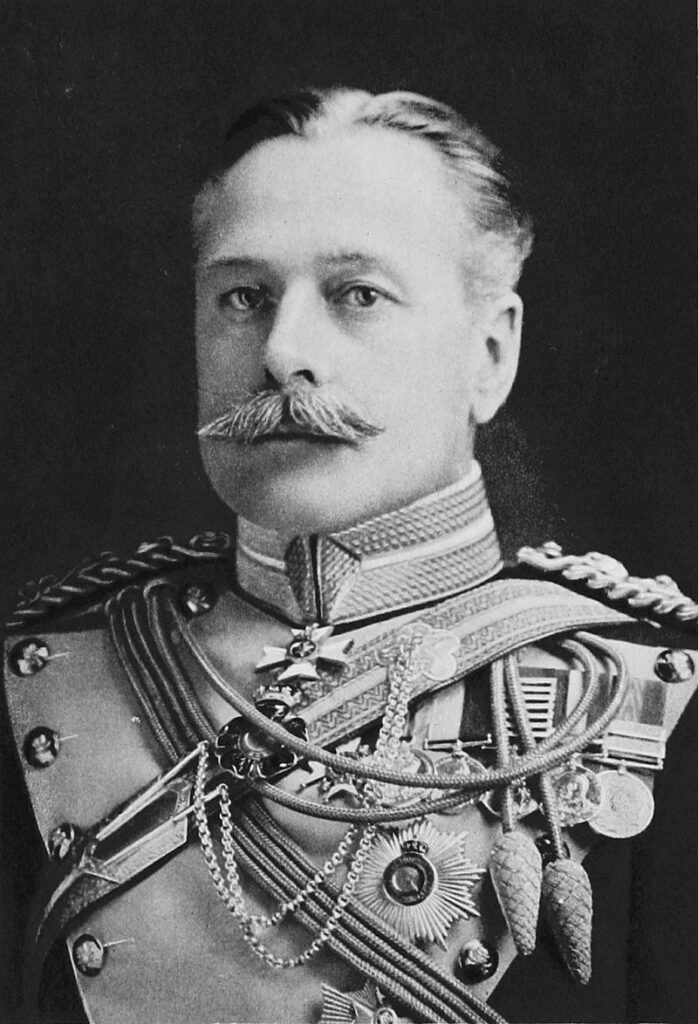

2. Douglas Haig

If Joseph Joffre’s legacy as a WWI commander is contradictory, then Douglas Haig’s is downright schizophrenic. Haig was the commander of the British forces for most of WWI, starting from when he assumed the post in 1915. Though his time in charge saw the Allies triumph on the Western Front and finally defeat German forces in the field, the victory cost the lives of tens of thousands of soldiers.

Despite his role in winning WWI for the Allies, Haig has the ignominy of being the most frequent recipient of the “donkeys leading lions” description. Some of his contemporaries, like British Prime Minister Lloyd George and future PM Winston Churchill, publicly criticized Haig’s decisions as leader of the British forces.

The most common grievances against Haig were his stubborn adherence to the principles of attritional warfare, which his critics felt led to unnecessarily high casualties.

The most glaring examples of Haig following the attritional approach for very little military gains were the Battle of the Somme and the Third Battle of Ypres. Over the course of these two battles, which stretched on for weeks in 1916 and 1917, respectively, over 130,000 British soldiers were killed on the battlefield.

For his part, Haig defended his decisions as a commander by insisting that the long-drawn confrontation in the trenches of the Western Front was necessary to weaken the German forces before a final victory could be won.

Recent efforts have been made by historians to recontextualize Haig’s accomplishments during WWI. After all, this was the first conflict of such a scale that the world had ever seen, and it took place at a time when military technology was rapidly advancing.

It’s worth mentioning that Haig inherited a very different military than he left to his successors. Even as he faced a daunting enemy in a high-stakes conflict, Haig was able to modernize the British military. After WWI, the British military had an armored division and an air force for the first time in its history.

The Allies’ final offensive against the Germans in 1918 successfully incorporated Haig’s “All Arms” strategy, which called for tanks, artillery, infantry, cavalry, and air power to be used in unison.

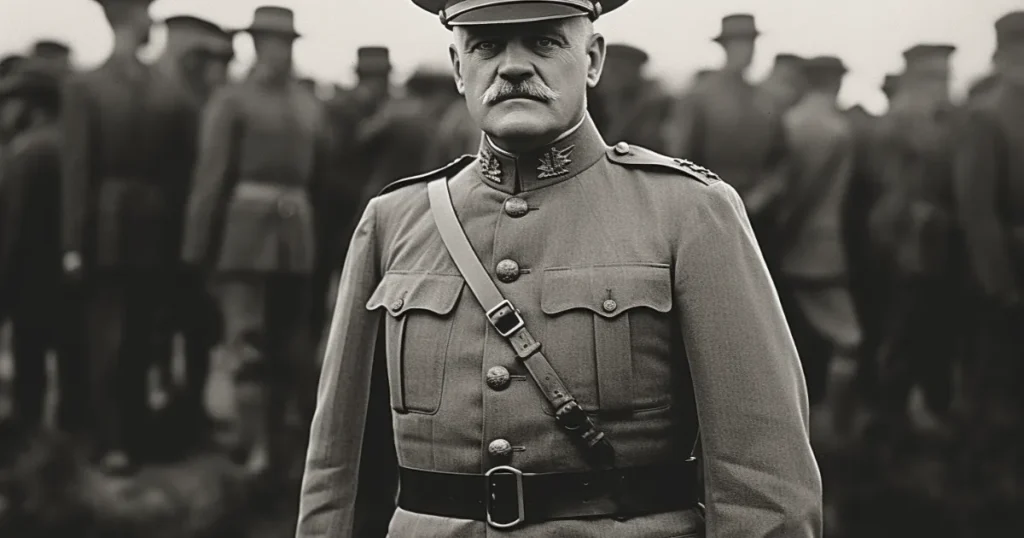

3. John J. Pershing

The U.S. entered WWI late, only joining as an official belligerent in 1917. By then, the Allies had been fighting the Central Powers across Europe, Asia Minor, and the Middle East for three long years. They desperately needed reinforcements to hold back the Germans, who were themselves strengthened by the withdrawal of Russia from the Eastern Front.

Those reinforcements arrived in the shape of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), led by General John Joseph Pershing.

Pershing was a natural choice to lead the AEF during WWI. He had already served in far-flung theaters of conflict, like the Spanish-American War in Cuba, putting down rebels in the Philippines jungles, or chasing down the notorious Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa in the desert.

His AEF was to travel across the Atlantic to help the Allies repel the rejuvenated German advance. But before he could achieve that objective, Pershing needed to mold the two million, largely untrained, soldiers of the AEF into a well-oiled fighting machine.

When he first arrived in Europe, Pershing had to contend with his fellow Allied commanders looking to absorb units of the AEF into their own divisions. Even though the French and British divisions were greatly depleted, the U.S. general was vehemently opposed to this plan.

He believed that the AEF would be a more effective force if unified under a single command rather than used to seed the ranks of the other countries’ armies. This attitude did put Pershing at odds with other Allied commanders at first, but he was proved right as the war went on.

By 1918, the two million-strong AEF was a force to be reckoned with on WWI battlefields. Under Pershing, the AEF inflicted defeats on the Germans in several important battles, such as Catigny, Chateau-Thierry, and St. Mihiel. Pershing and the AEF were also instrumental in the Allied victory in the Meuse-Argonne offensive in 1918, which resulted in Germany finally seeking an armistice.

Unlike many of his fellow Allied commanders during WWI, Pershing was spared the negative characterization of WWI generals. In fact, he was given the honor of being only the second American after the nation’s Founding Father, George Washington, to be awarded the rank of General of the Armies of the United States.

4. Ferdinand Foch

Every campaign requires a supreme commander. For the Allies in WWI, Ferdinand Foch was that man. Though he did not start WWI by leading the entire Allied force, his elevation to the post of commander-in-chief provided new momentum to the war effort.

Before WWI began, Foch was approaching the end of his military career. He had already served as an artillery officer, rising to the rank of brigadier general over the course of a career that spanned three decades. Foch had already built a reputation as a military strategy expert, serving as the head of École Supérieure de Guerre, France’s top military institute.

The sudden outbreak of WWI saw Foch called into service once again. He fought in the Battle of the Frontiers, where he successfully repelled the German advance through Lorraine. This brought him to the notice of General Joseph Joffre, who was France’s commander-in-chief at the time.

Foch’s tenacity and ability to resist the German advances proved instrumental in the First Battle of the Marne in 1914. Thanks to Foch’s defensive maneuvering, French forces were able to prevent the German forces from taking Paris.

Over the next two years, Foch would spend his time in action on the Western Front while command of the French forces passed from Joffre to General Robert Nivelle and finally to General Phillippe Pétain. During this time, the situation on the Western Front continued to deteriorate, as both Allies and Central Powers threw soldiers at the other’s trenches in an often futile yet always bloody effort to win ground.

By 1918, German pressure on the Western Front was mounting due to Russia’s withdrawal from the war. The German forces could focus entirely on the Western Front, and they had the advantage in terms of men and materials. Foch was given supreme command of Allied forces in these dire circumstances.

Still, he managed not only to withstand the German assault but also to hold on to strategically important positions until the arrival of American reinforcements. It was Foch who coordinated the final counterattack that saw the Allies finally break the German lines and force a surrender, bringing an end to WWI.

The conclusion of WWI was the dawn of a new era in world history. Never before had a single war had such a wide-reaching effect on global politics.

By the time WWI ended, four imperial dynasties had fallen, several new nationalist movements had emerged in Europe, and the U.S. had come into its own as a world power for the first time. The new world order that emerged after WWI was made possible thanks to the efforts of commanders like Haig, Pershing, Foch, and many others.