Saying that we have a tumultuous relationship with the media and journalism these days is an understatement. Every bit of news that comes out has its naysayers and those who insist that it just isn’t true. This distrust for journalism of all sorts isn’t new, though. In fact, it’s been around since the 1890s, and actually has a name associated with it–yellow journalism.

Yellow journalism isn’t fake news, per se, but instead, is journalism that uses attention-grabbing headlines while having very little substance otherwise. This type of journalism relies on sensationalizing even the mundane, just to draw readers in.

The headlines could be used to shock and mislead readers while also making the stories within sound irresistible. In this way, the newspapers that partook in the yellow journalism trend were able to sell quite a few more papers than usual.

While the idea of yellow journalism seems simple enough, it actually has a long, somewhat convoluted history. Let’s look a little deeper into this unsavory practice and its storied past.

What is Yellow Journalism?

Yellow journalism refers to a style of journalism that leans towards sensationalistic, and even false, claims and headlines to boost readership and sales. This style of journalism takes advantage of the emotions of the readers, catching their attention and making consumers feel like they have to know what the story is about.

Unfortunately, beneath the eye-catching headlines, the stories associated with yellow journalism often lacked truth and accurate reporting. Instead, it would exaggerate and distort the truth to appeal to the readers, even at the cost of honesty.

A few yellow journalism examples are:

- “Remember the Maine! To Hell with Spain!” –The New York Journal, 1898

- When the USS Maine sank in the Havana harbor in Cuba, suspicions were immediately high. Newspapers like the Journal were quick to blame Spain for the explosion, even when there were no concrete conclusions about the real cause of the tragedy. Headlines like these drummed up anti-Spain sentiment and played a big part in the outbreak of the Spanish-American War.

- “Peace Treaty Ratified, Awful Slaughter” –The New York Journal, 1899

- Another sensationalist headline in the New York Journal, this article used the words “Awful Slaughter” to full effect, printing them in bold, capital letters, much larger than any other headlines. Referencing the Philippine-American War, the Journal made sure to drum up negative emotions in order to convince readers to purchase the paper so they could read about this so-called slaughter.

The Beginning of Yellow Journalism

Born in the late 1800s, yellow journalism first appeared in the newspapers of the day. Specifically, the trend was started during a feud between two New York City newspapers, the New York World and the New York Journal.

The two papers were competing for readers, but the heart of this feud was actually between the publishers Joseph Pultizer, of the Pulitzer prize fame, and William Randolph Hearst.

Pulitzer had bought the New York World in 1883, turning the relatively small paper into one of the biggest in the country using yellow journalism. Even if it didn’t have the yellow journalism moniker at the time, Pulitzer was clearly sensationalizing the headlines in his paper, reporting on politics and social issues that were close to the hearts of many New Yorkers.

At first, he stood unchallenged, but in 1895, that all changed. William Randolph Hearst arrived in New York City and quickly bought the rival newspaper to the New York World, the New York Journal.

Hearst, the son of a mining tycoon from California, was experienced with bringing success to newspapers. His previous paper, the San Francisco Examiner, was a huge success back in California, and by the time Hearst moved to New York, he was ready for a repeat with the Journal.

The Rivalry Heats Up

Once Hearst acquired the Journal, he started to hire journalists and cartoonists to fill out his new paper. One employee that he lured away from the New York World was comic author Richard F. Outcault.

Richard’s comics were one of the biggest draws of the World, and thus, when he switched teams, his readers from the World were quick to switch to the Journal. A character from one of Richard’s comic strips, Hogan’s Alley, would be the inspiration for giving yellow journalism its name.

This character was aptly named The Yellow Kid and was a bald child wearing a long yellow shirt. With loud, brash dialogue and catchphrases on his yellow smock, The Yellow Kid was a fitting mascot for yellow journalism and was even more fitting for the fact he had been featured in both the World and the Journal at different times.

The name “yellow journalism” was first created by Edwin Wardman, an editor of yet another New York paper, the New York Press. He was the first to publish the term, using both “yellow journalism” and “yellow kid journalism” to refer to the type of writing coming out of the Pulitzer-Hearst feud.

Yellow Journalism and the Spanish-American War

The rivalry between Heart and Pulitver hit its peak between the years of 1895 and 1898, and this just so happened to coincide with the start of the Spanish-American War. When it comes to dramatic, overblown headlines, there is no better fodder than war.

It all began with the Cuban War of Independence in Spain’s Cuban colony. Both Heast and Pulitzer printed stories greatly exaggerate the conflict, which involved Cuba looking to become independent. Both publishers were hyper-critical of the Spanish occupation, even printing false stories just to garner attention. It wasn’t long, though, before the conflict would provide even more yellow journalism material for the World and Journal.

In 1898, the American battleship, the U.S.S Maine, had docked in the Havana harbor in Cuba. Its presence was meant to be a display of power for the U.S. and to help keep the simmering conflict between Spain and Cuba from boiling over into the United States.

The Maine wasn’t there long before tragedy struck. On February 15, 1898, an explosion ricocheted through the harbor, originating from the American battleship. The explosion was violent and devastating for those aboard the ship–266 of the 354 people aboard the ship perished.

Even now, there is no concrete explanation for the sinking of the Maine, but at the time, the prevailing idea was that Spain had sunk the battleship. This idea was spurred on by yellow journalism coming from newspapers across the United States, but the New York World and New York Journal were exceptionally harsh and sensationalistic.

Hearst especially was fixated on fanning the flames of war. One quote had him telling artist Frederic Remington,

“You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the war.”

With anti-Spain sentiment at an all-time high, the public in New York City was clamoring for stories that reflected their already strong opinions. So while Hearst, and to a lesser extent, Pulitzer, would publish stories with varying degrees of truth in them, readers still purchased the papers. They didn’t need to be convinced that the stories in the paper were truthful–their minds had already been made up, and the yellow journalism in the papers only validated these already existing opinions.

It’s not known if the yellow journalism in these publications swayed political officials one way or the other when it came to the war with Spain. War was inevitable, though, and once a naval investigation came to the conclusion that the Maine must have been sunk by an underwater mine, yellow journalism had people ready to enter the fray.

In May of that same year, the Spanish-American War began in earnest. Hearst and Pulizter continued to produce pieces that were more inflammatory than they were honest, but in just a few short years, their guilt started to catch up to them.

In response, Hearst traveled to Cuba to report on the atrocities of the war firsthand, giving an honest view of the country and the battle for independence they were facing. Pultizer didn’t leave the country, but he did shift the focus of his paper back to its ethical journalistic roots.

Yellow Journalism After the Spanish-American War

Once the war had ended, the influence of yellow journalism could still be seen in papers across the country, but its effects were gradually diminishing. Publications were starting to see the value of ethical journalism over yellow journalism, and how important it was to report things factually instead of relying so much on sensationalism.

The gradual shift towards more responsible reporting continued through the 20th century, with the Society of Professional Journalists being established in 1909. This society advocated for ethical journalism practices and emphasized accuracy, fairness, and integrity instead of relying on flashy, attention-grabbing pieces.

As for Hearst and Pulitzer, their rivalry also dimmed once the war was over. Hearst tried his hand at entering the political field but had little success. He faced outrage when articles published in his paper called for the assassination of President McKinley, who was later shot on September 6, 1901.

Hearst insisted that he was unaware of the articles, and the one that he was made aware of he pulled from the paper right away. Even so, critics of Hearst accused him and his yellow journalism of playing a possible part in driving the shooter, Leon Czolgosz, to act.

Pulitzer, on the other hand, spent time rebuilding the tarnished reputation of his paper until it was a respected publication instead of a tabloid-esque haven for yellow journalism. After his death, his successes and innovations in the world of journalism led Columbia to create the Pulitzer Prize awards for outstanding journalism.

Yellow Journalism in the Present Day

Even though the heyday of yellow journalism has long since passed, it lives on in many types of media today. The twenty-four-hour news cycle and the availability of the internet make it incredibly easy to access these entertainment-based types of news media.

Tabloids are the most notorious successor to yellow journalism, using scintillating headlines and paparazzi photos to garner readers’ attention. They are considered classless, and even predatory in nature, similar to how yellow journalism was viewed in the late 1800s.

Another more recent offspring of yellow journalism are clickbait articles on the internet. Almost identical to the tactics of yellow journalism, clickbait uses irresistible, often misleading titles to get internet users to click on web pages and videos. These clickbait articles or videos will often use sensationalized, edited pictures to grab attention, too.

Characteristics of Yellow Journalism

- Sensational headlines- As previously stated, attention-grabbing headlines are the cornerstone of yellow journalism. Altering the truth to fit these headlines and cause the strongest emotions was the goal. Strong emotions equal more sales.

- Emphasis on Scandal- Important issues like politics and world events sometimes seem boring compared to smaller-scale, scandalous stories. Because of this, another characteristic of yellow journalism is a focus on stories about scandal and crime over real, objective reporting on events that really matter.

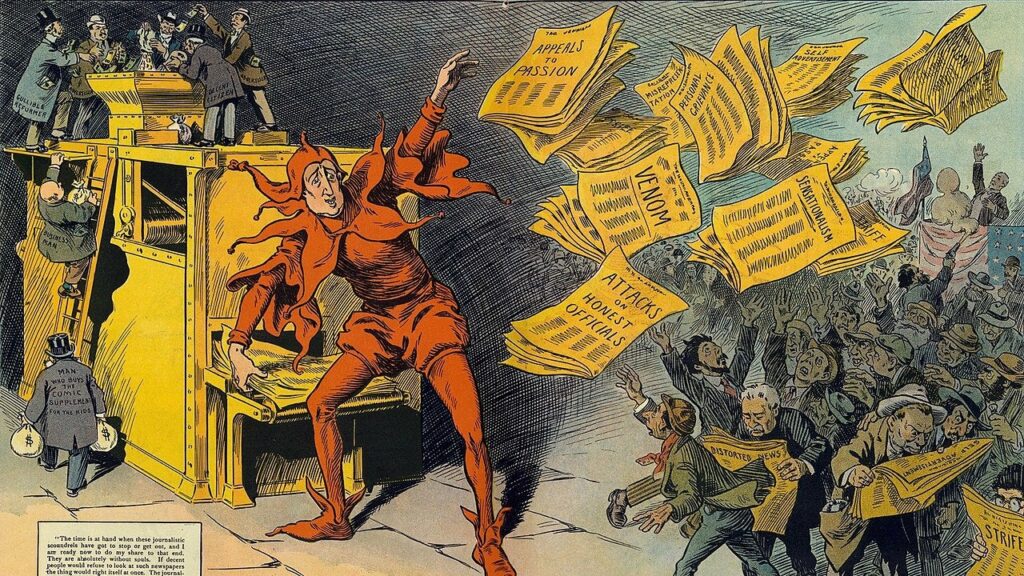

- Illustrations- One of the first examples of yellow journalism was a cartoon known as “The Yellow Kid”. Keeping up with this trend, comics and illustrations often accompanied articles that utilized yellow journalism with the intention of grabbing the attention of potential customers with their bright colors and often inflammatory subjects.

- Political Influence: Since yellow journalism was often untruthful, it wasn’t unheard of for the newspapers that featured yellow journalism to have a political agenda. Publishers would use their papers to push their political opinions, writing headlines and articles that were blatantly false and passing them off as truth to try and make their preferences appear to be reality. These sorts of yellow journalism examples were especially notorious, as their existence made it difficult for the public to research politics and form their own opinion with everything being presented as fact and written with a specific agenda in mind.

References

“U.S. Diplomacy and Yellow Journalism, 1895–1898”

“Yellow Journalism”